ASTR 1210 (O'CONNELL)

SELECTED MARS IMAGES

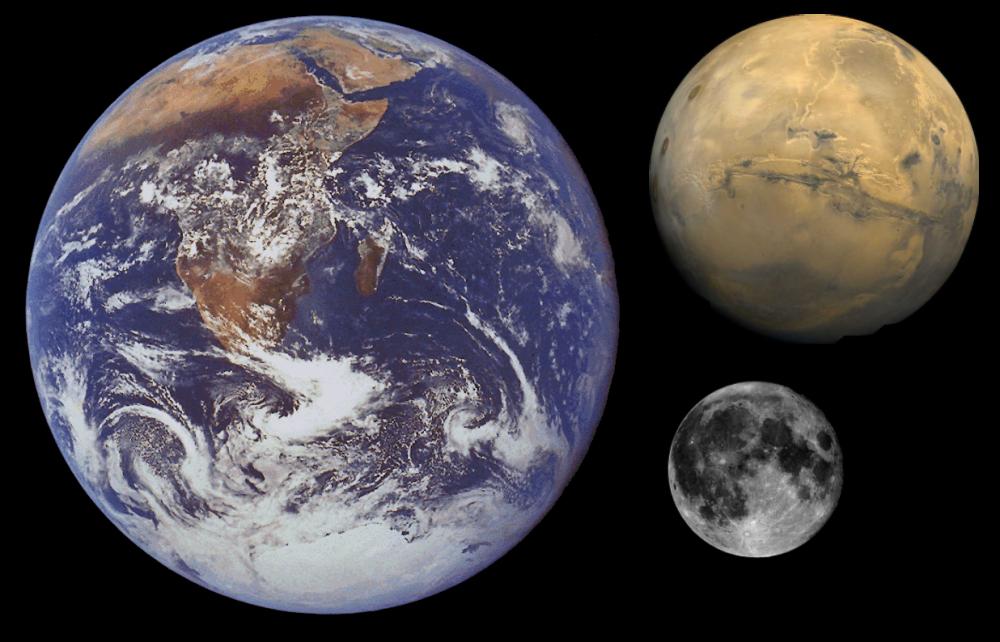

Mars features the most interesting surface of any planet other than

Earth. Even though Mars is a smaller planet, its land area is about

the same as Earth's (since two-thirds of Earth's surface is covered by

oceans). Mars' terrain is an exaggerated version of the Earth's. The

spacecraft campaign of orbiters and landers which began in the

mid-1990's has yielded an enormous amount of information on Mars.

You can find a large number of beautiful Mars images taken by

terrestrial telescopes and spacecraft on the Web. Some of the better

sites are linked to the

Study Guide 16 page on Mars.

Here, I've selected images which illustrate the variety of terrain on Mars

and the extent to which we are now able to study it from spacecraft.

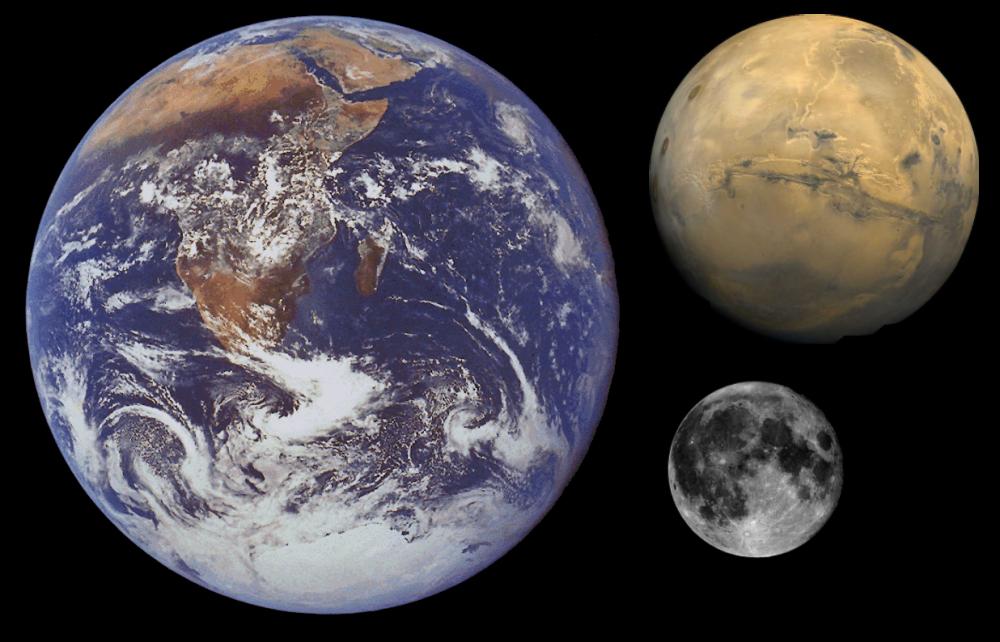

Earth, Moon, and Mars Compared to Scale

|

|

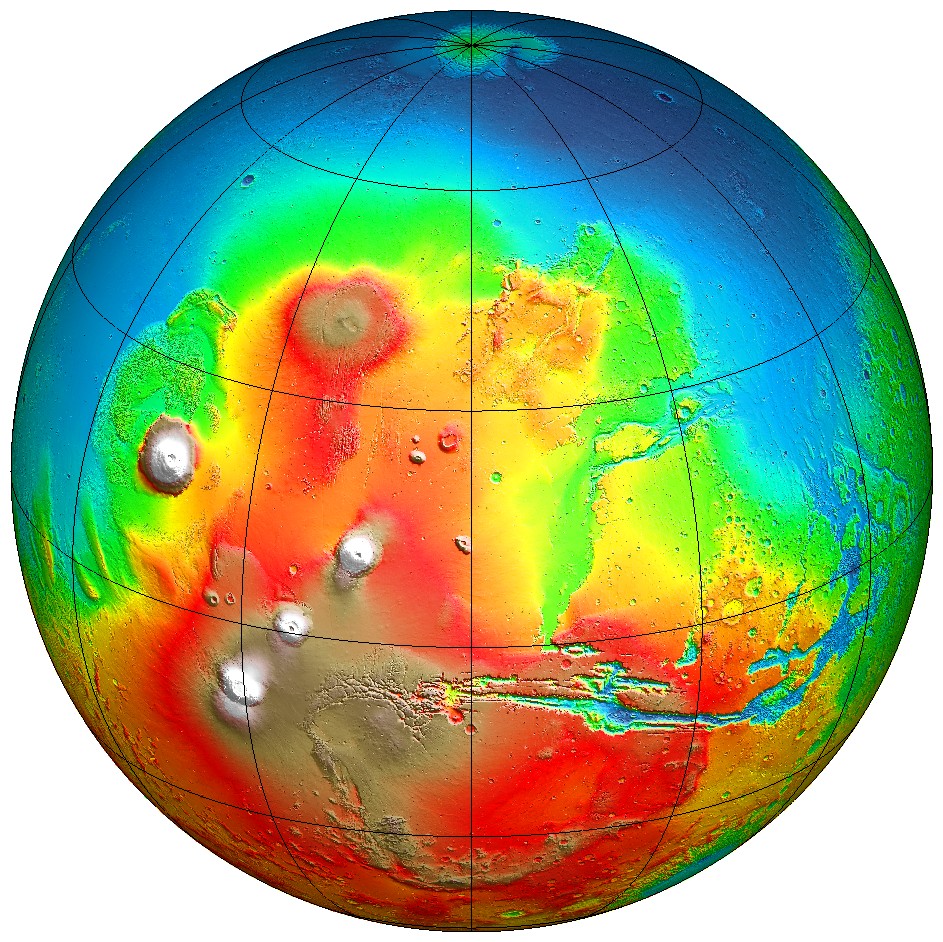

| THARSIS HEMISPHERE |

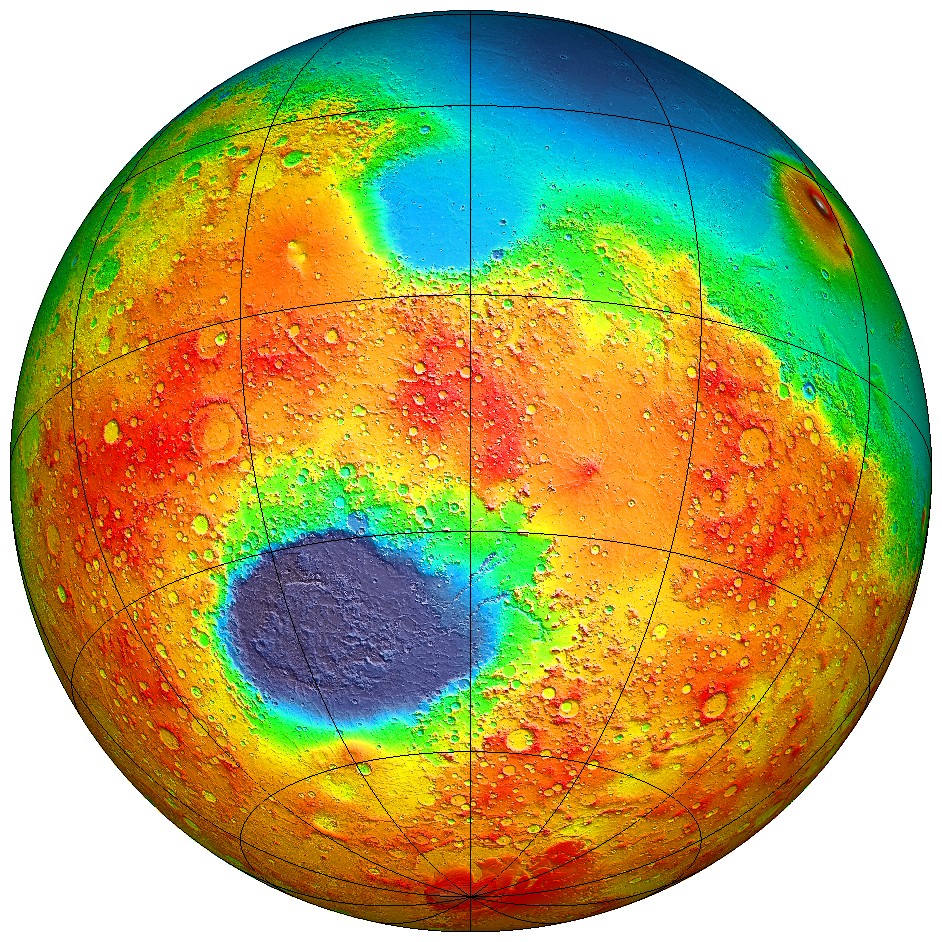

HELLAS HEMISPHERE |

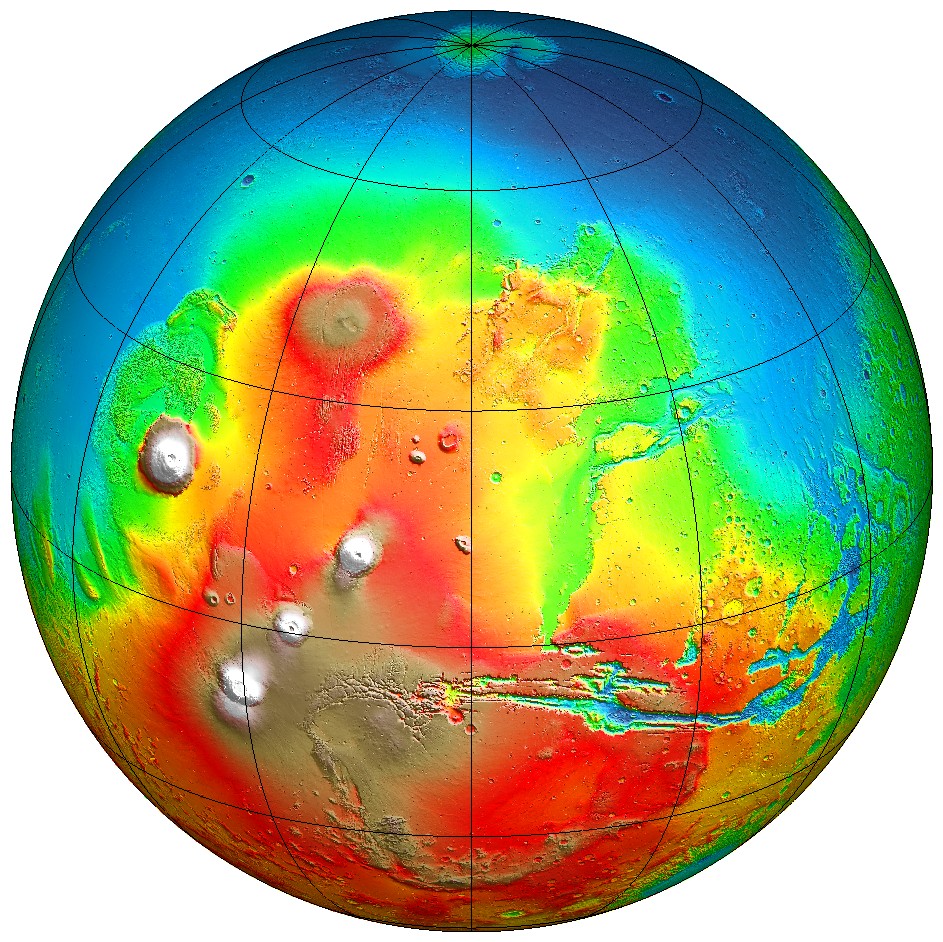

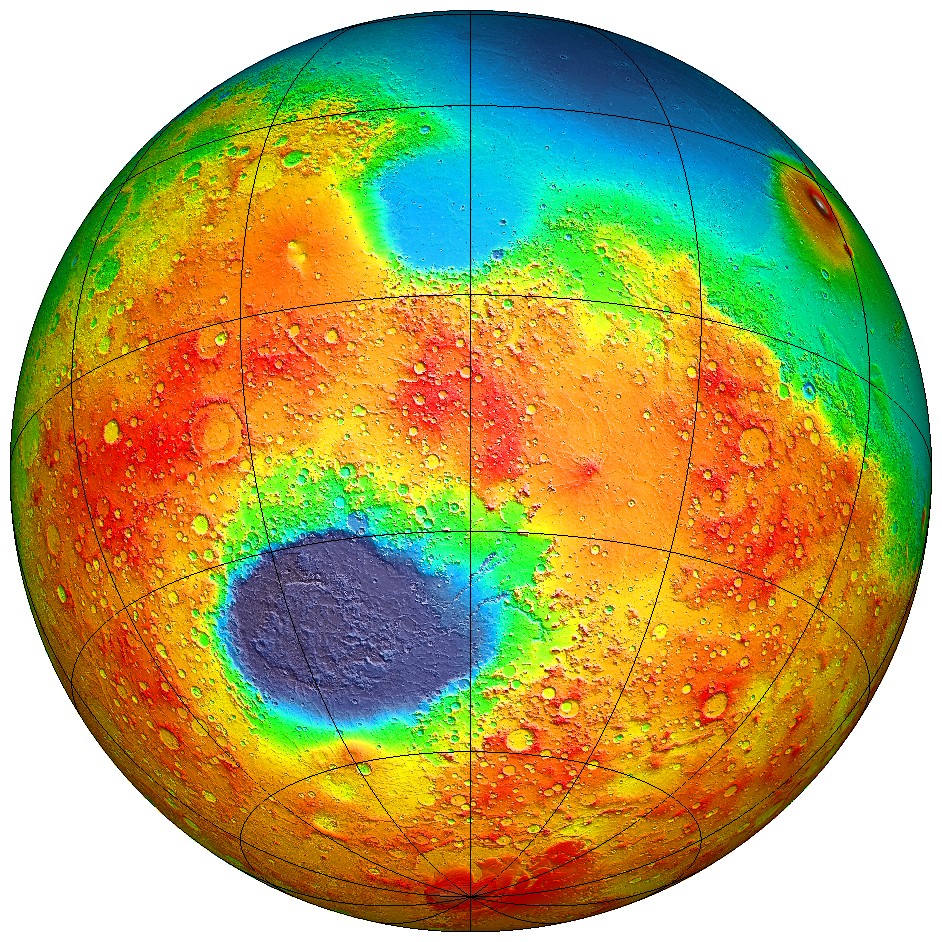

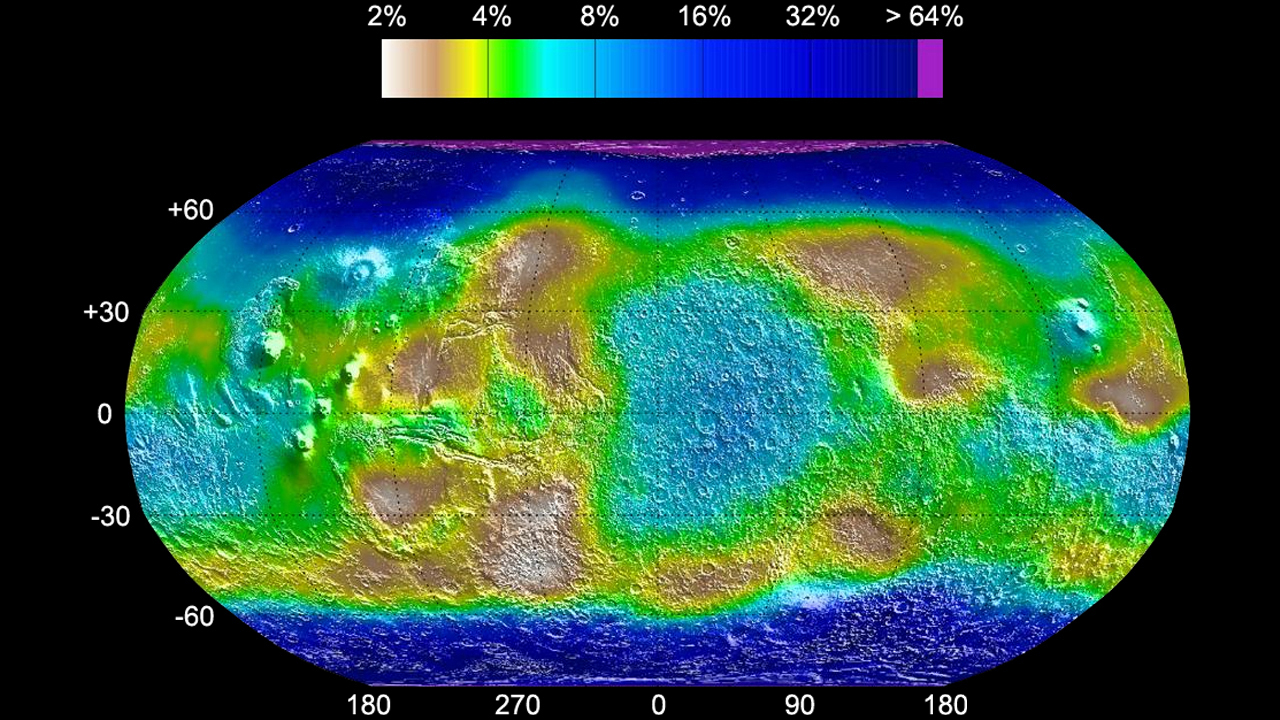

MOLA Maps of Mars

Topographic maps produced by the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA)

on the Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) mission (1998-2006). Left: Tharsis

hemisphere. Right: Hellas hemisphere. Color coding is for altitude

(blue is lowest, red high, white is highest---but doesn't indicate

snow). Click on the images for larger versions. For a high-resolution

enlargement, click

here.

Identifications for the various Martian features visible here are

given

here (main areas),

here (details), or in a

large-format poster

here.

The Tharsis hemisphere is dominated by the

"Tharsis Bulge" a huge, elevated surface

deformation which produced striking volcanoes and canyons. The Hellas

hemisphere consists mainly of cratered highlands, punctuated by a

single enormous impact basin (

Hellas). The cratering density shows

that the Tharsis hemisphere is significantly younger, on average, than

the Hellas hemisphere. Tharsis is probably 2-3 billion years old.

An even more remarkable asymmetry revealed by the MOLA altitude maps is

the large 5 km (16,500 ft) difference between the mean elevations of

the (low) northern hemisphere and the (high) southern hemisphere. The

north is less heavily cratered (meaning younger) and smoother. It is

dominated by a huge, flat depression (blue in the images above), which

may be the bed of an ancient

ocean.

[Images: MOLA Team]

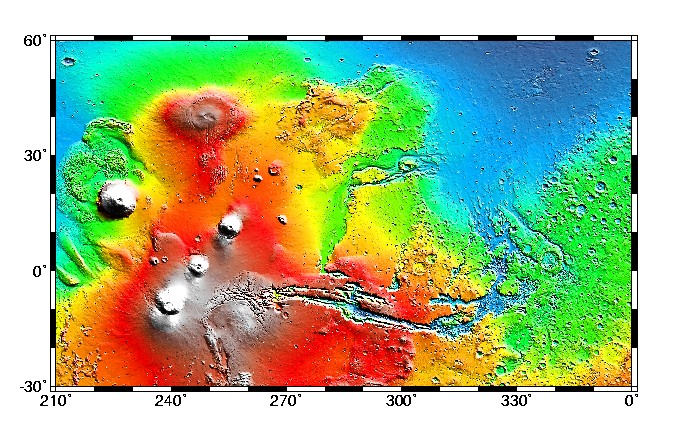

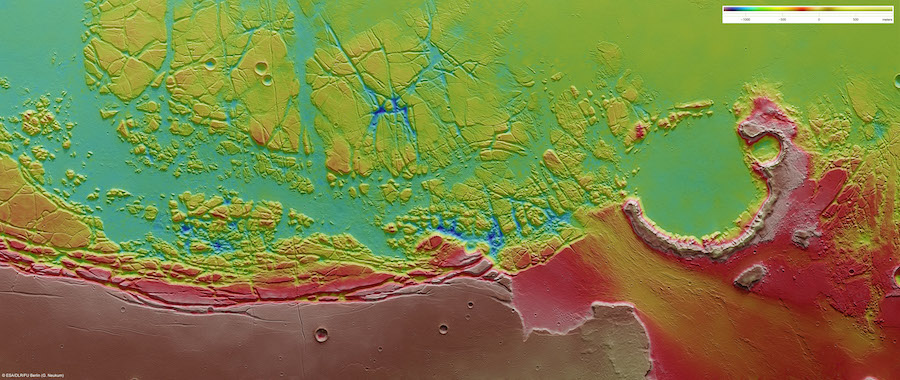

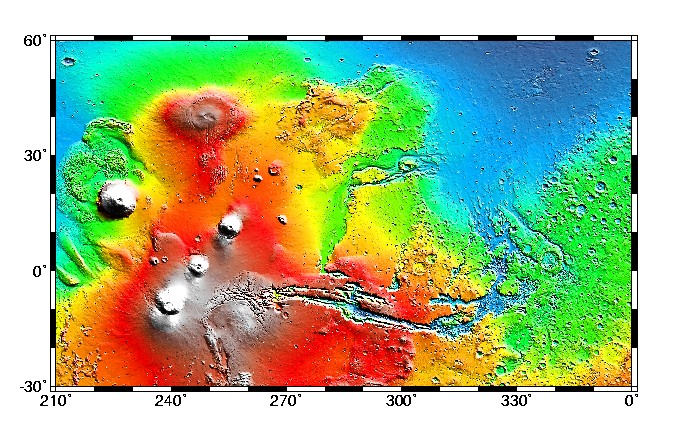

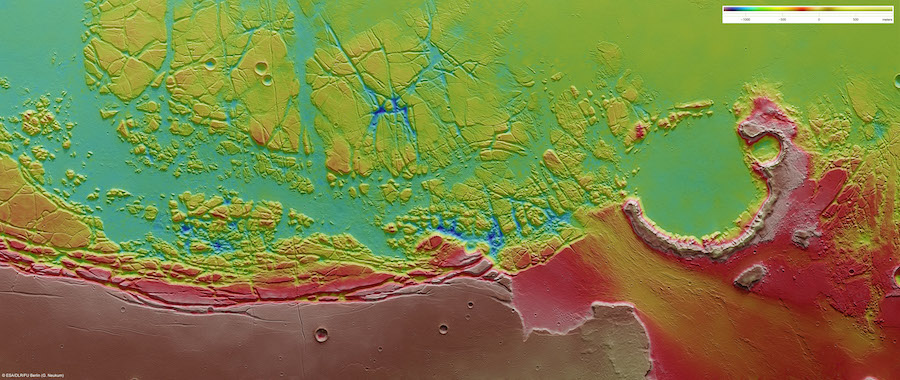

Map of Tharsis

MOLA map of the dramatic Tharsis (left) and Chryse (right) regions on Mars,

color-coded for altitude as above. Click on the map for a high-resolution

image of the area.

Clearly marked are the major Tharsis volcanoes: Olympus Mons (the

isolated peak to the west at coordinates 18N, 228E), Alba Patera (40N,

250E) and the volcanic chain consisting of Ascraeus, Pavonis and Arsia

montes. In the lower center of the map is the gigantic Valles

Marineris canyon system (stretching from 265E to 310E). At the right

side are the Chryse channels, running toward the northern plains. The

large red (high altitude) blotch corresponds to

the

"Tharsis Bulge."

Although the Tharsis Bulge itself is thought to be over 3 billion

years old, volcanic activity in the form of smooth lava flows

continued in some areas there until as recently as 100 million years

ago. There is even improving evidence that some small flows occurred

in the last few million years. Mars may not be quite as dormant

a planet as had been assumed.

[Image: MOLA Team]

Volcano Olympus Mons

Olympus Mons, located west of the Tharsis bulge, is the largest volcano

known in the Solar System, with an altitude of 88,000 feet

(

compare to

Mt. Everest at 29,000 ft above sea level and 43,000 ft above the ocean

floor), a diameter of 340 miles, a

caldera 44

miles in diameter and flanking cliffs reaching 20,000 feet in

altitude. If situated in Virginia, it would occupy most of the land

area of the state. It is a shield volcano, like the large volcanos in

Hawaii. These tend to have relatively quiescent eruptions of fluid

lava, without the explosiveness associated with ash eruptions or more

viscous lava (as in Mt. St. Helens). The massive concentration of

magma which built up Olympus Mons and the Tharsis bulge apparently

originated in an enormous

mantle plume.

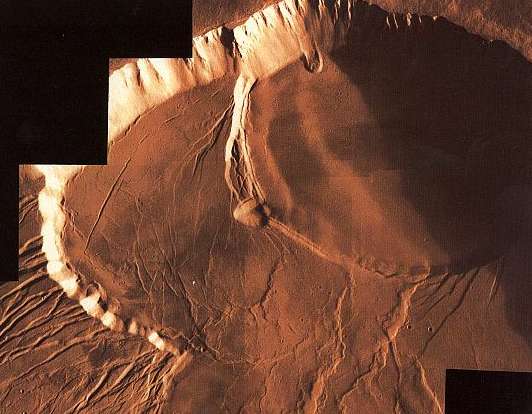

This is a composite of Viking images, projected in perspective as if

seen from an altitude of about 30 miles at a distance of about 1500

miles.

Here is a mosaic looking straight down on Olympus Mons.

Caldera of Olympus Mons (Viking)

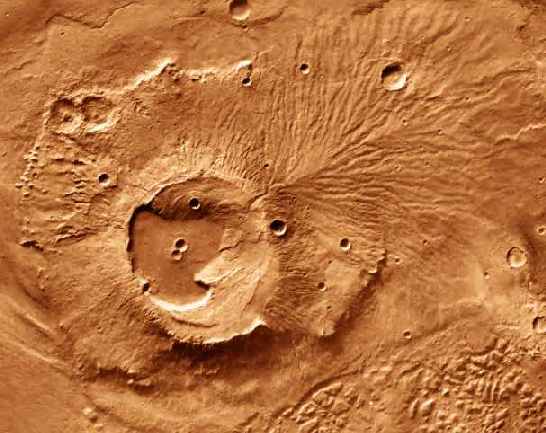

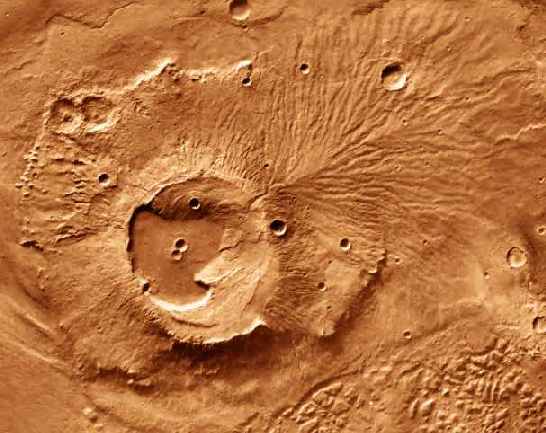

Volcano Apollinaris Patera

This view of Apollinaris Patera, shows characteristics

of an explosive origin and an effusive origin. Incised valleys in most

of the flanks of Apollinaris Patera indicate ash deposits and an

explosive origin. On the west side (bottom), landslides that have shaped

its surface also indicate ash deposits. Towards the south flank, a

large fan of material flowed out of the volcano. This indicates an

effusive origin. Perhaps during its early development Apollinaris

Patera had an explosive origin with effusive eruptions taking place

later on. [Image & caption by Calvin J. Hamilton.]

Ceraunius Tholus

A Viking vertical view of Ceraunius Tholus, a "small" volcano in the

Tharsis Bulge just north of the chain of three large Tharsis volcanos

described

above. Ceraunius is about

21000 feet high; the caldera at the summit is about 15 miles across.

The true base of the volcano is submerged in the flood of lava which

produced the surrounding Tharsis plain.

Here is a

perspective view, created in software from Mars Express images, from

the top of Ceraunius' caldera.

Gigantic stress fractures caused by

the

upwelling of magma from below

cross this region. Click the image for an enlarged view.

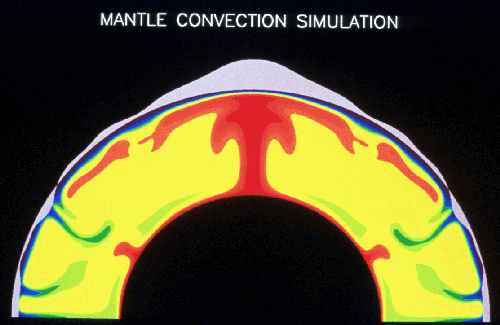

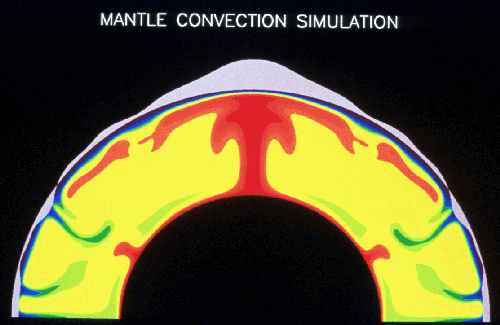

Tharsis Plume Computer Simulation

This image shows a computer simulation of processes

in the interior of Mars that could have produced the Tharsis region.

The color differences are variations in temperature. Hot regions are

red and cold regions are blue and green, with the difference between

the hot and cold regions being as much as 1000 C (1800 F). Because of

thermal expansion, hot rock has a lower density than cold rock. These

differences in density cause the hot material to rise toward the

surface and the cold material to sink into the interior, creating a

large-scale circulation known as mantle convection. This type of

mantle flow produces plate tectonics on Earth.

The hot, rising material tends to push the surface of the planet up,

and the cold, sinking material tends to pull the surface down. These

motions contribute to the overall topography of the planet. This

deformation of the planet's surface is shown in gray along the outer

surface of the planet in this image. The amount of deformation is

highly exaggerated to make it visible here. The actual uplift in

Tharsis is estimated to be about 8 kilometers (5 miles) at its center.

This uplift also stretches the crust, forming features such as grabens

and

Valles Marineris. In addition, the hot,

rising material may melt as it approaches the surface, producing

volcanic activity. [Simulation & caption by Walter

S. Kiefer and Amanda Kubala, LPI.]

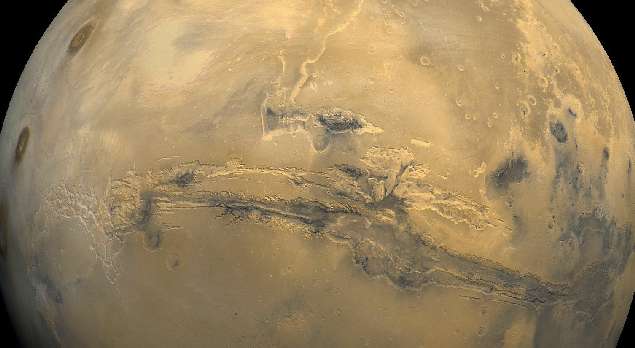

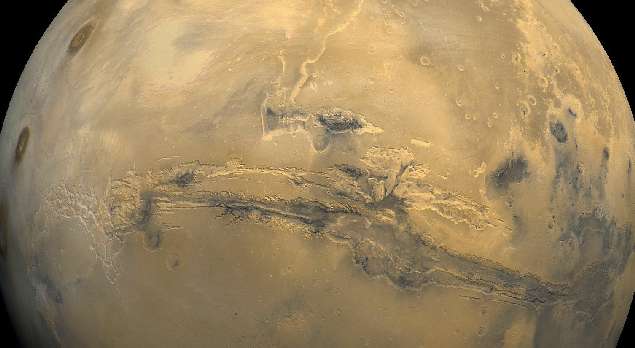

Valles Marineris

This great rift canyon on Mars, seen here in a Viking mosaic image, has a

length of 2400 miles (it would reach from Washington, DC to Los

Angeles), a maximum width of 70 miles, and a maximum depth of 22,000

feet. It is vastly

larger than

the US "Grand" Canyon, which would barely qualify as a "side channel"

here. Valles Marineris was not produced by water flow (although many

smaller Martian channels were). Instead, it appears to have formed by

a stretching and tearing of the Martian crust during the

Tharsis plume upwelling event.

Here

is a video animation (9 MB) of a "flyover," based on Mars Odyssey

images, which gives a good sense of the scale and structure of Valles

Marineris.

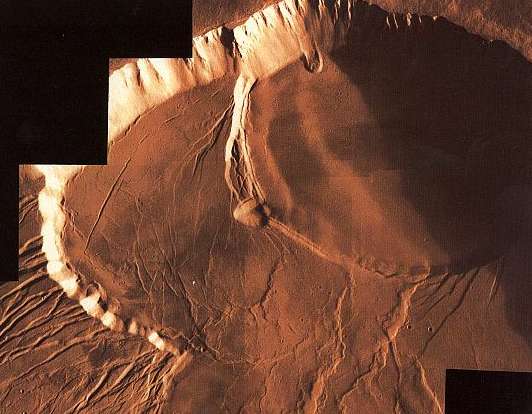

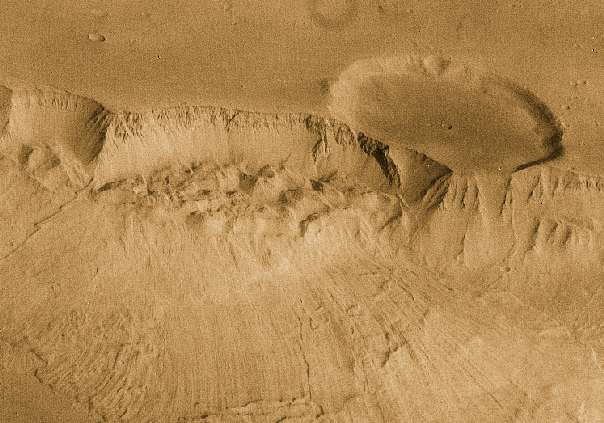

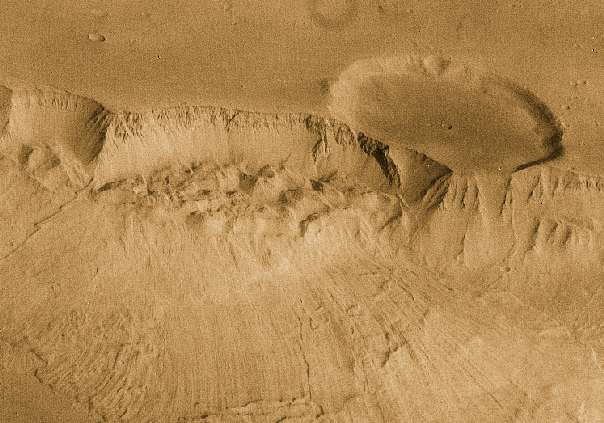

Ganges Chasma

A collapsed section of the south wall of Valles Marineris. The

transected crater is 10 miles across. The cliff walls are about

20,000 feet high, and the canyon is about 100 km wide. Click on the

image for a wide field view of another set of mega-landslides in the

northern Ophir Chasma canyon of Valles Marineris. [From

Viking images.]

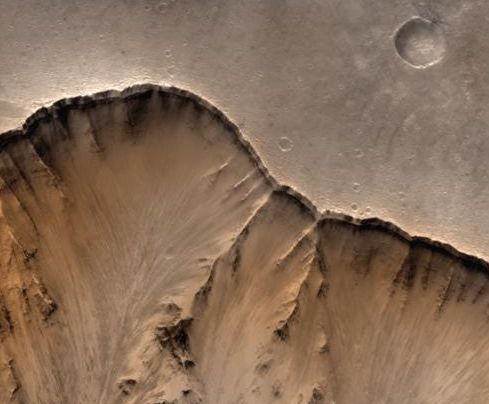

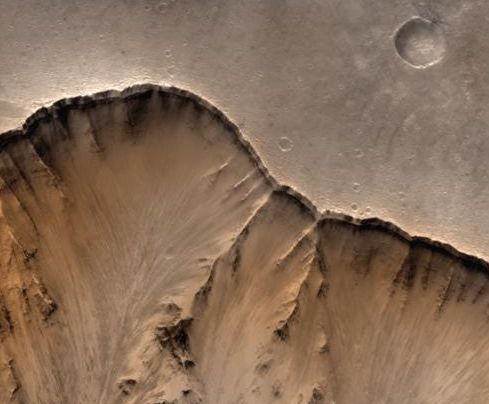

MGS Closeup of Valles Marineris Rim

Closeup of the rim of Valles Marineris showing details of cliff walls,

thousands of feet high. Layering is visible under the rim at the left

hand side. On Earth, such layers can be produced by both sedimentary

and volcanic processes. Both are also possible on Mars. Original

Mars Global Surveyor image has a resolution of 20 feet per pixel.

[Image by Malin Space Science Systems.]

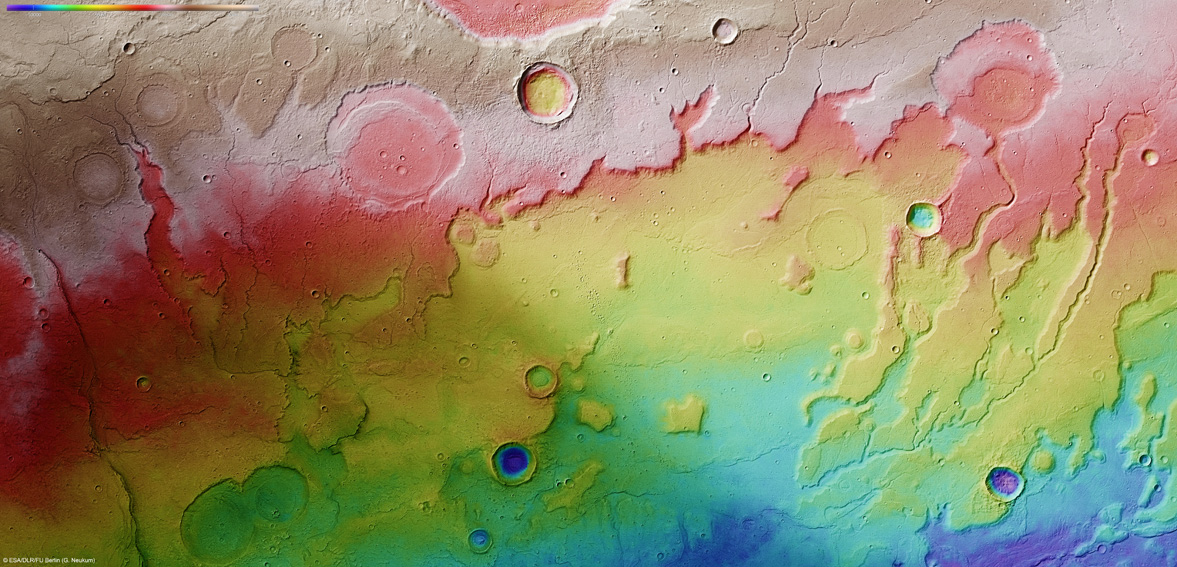

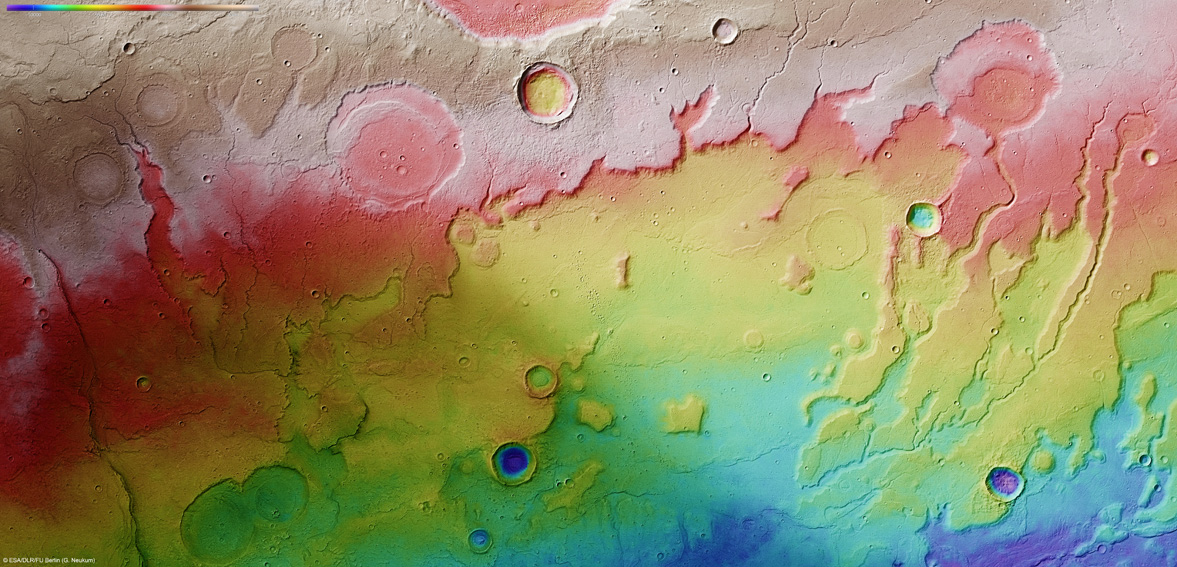

Hellas Impact Basin

A MOLA map of the Hellas impact basin, the largest on Mars. The upper

panel shows a cross section through the basin. It is 1400 miles

across and over 29,000 feet deep from the rim to its lowest point

(enough to accommodate Mt.Everest). It is surrounded by a huge volume

of excavated material, which, distributed evenly, would cover the

continental US to a depth of 2 miles. It is in the same league with,

but slightly smaller than, the

Aitken basin

on the Moon.

Here is a

graphic comparison of the two largest basins on Mars with the US.

Hellas is one of the few major topographic features on Mars that were

readily identified with telescopes on the Earth (see the best

Earth-based map

here.)

[Image by MOLA team]

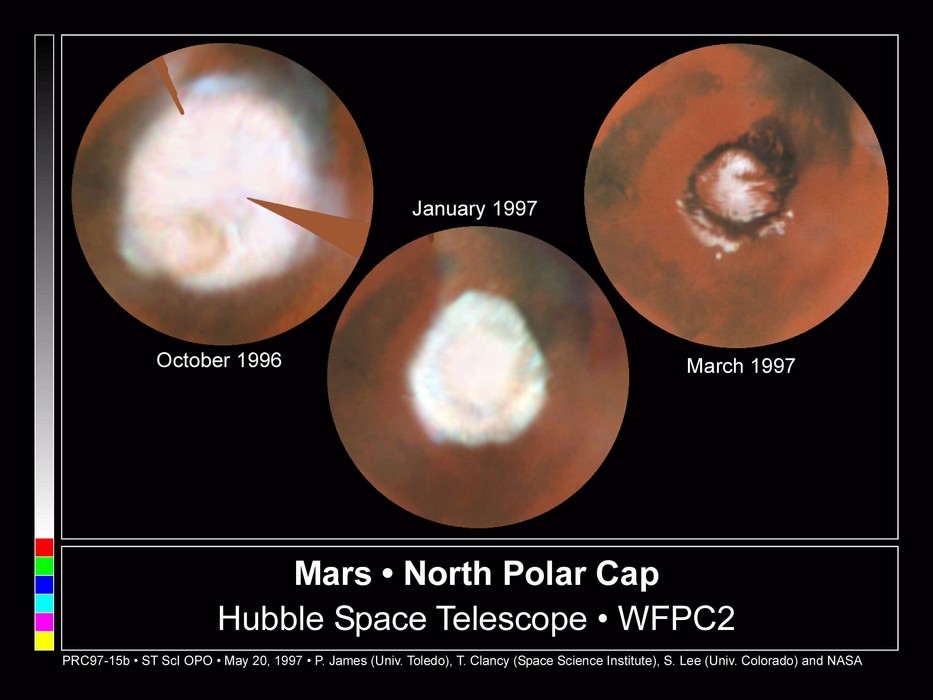

Views of Mars' Northern Polar Cap

The frame at the left shows Mars' northern polar cap shrinking from

its maximum size in winter to its minimum in summer (images taken from

near-Earth orbit by the Hubble Space Telescope). In winter the cap

is predominantly frozen carbon-dioxide ("dry ice"), whereas the persistent

summer cap consists of water ice. The spiral patterns that emerge in

summer are enlarged in the MGS image at the right, which has been digitally

rendered by R. Kosinski. The patterns are shaped by strong windflows.

The long, dark indentation is Chasma Boreale, a 300-km long canyon

reaching almost through the polar cap.

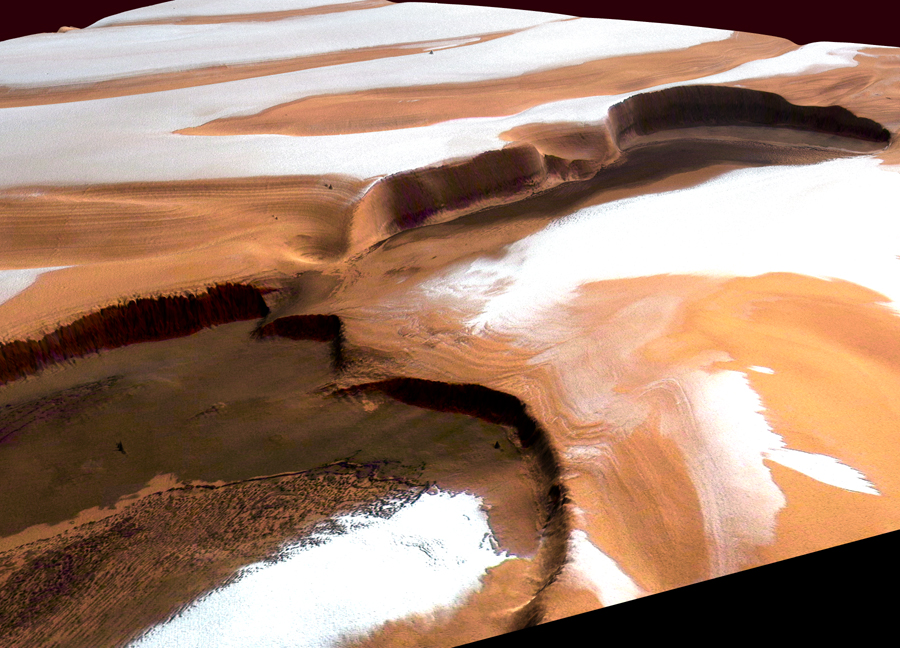

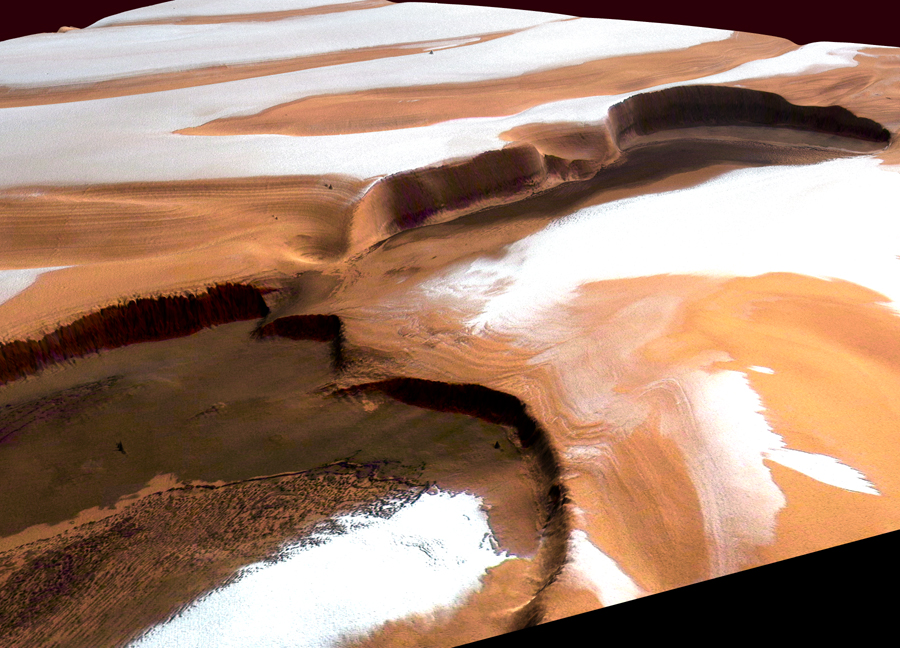

The Cliffs of Chasma Boreale

A perspective view, constructed from High Resolution Stereo Camera

images (Mars Express orbiter), showing parts of the canyon walls

of Chasma Boreale in summer. The cliffs here are nearly 2-km (6500

ft) high. The layered terrain is evident in the image. Residual

frost is water ice.

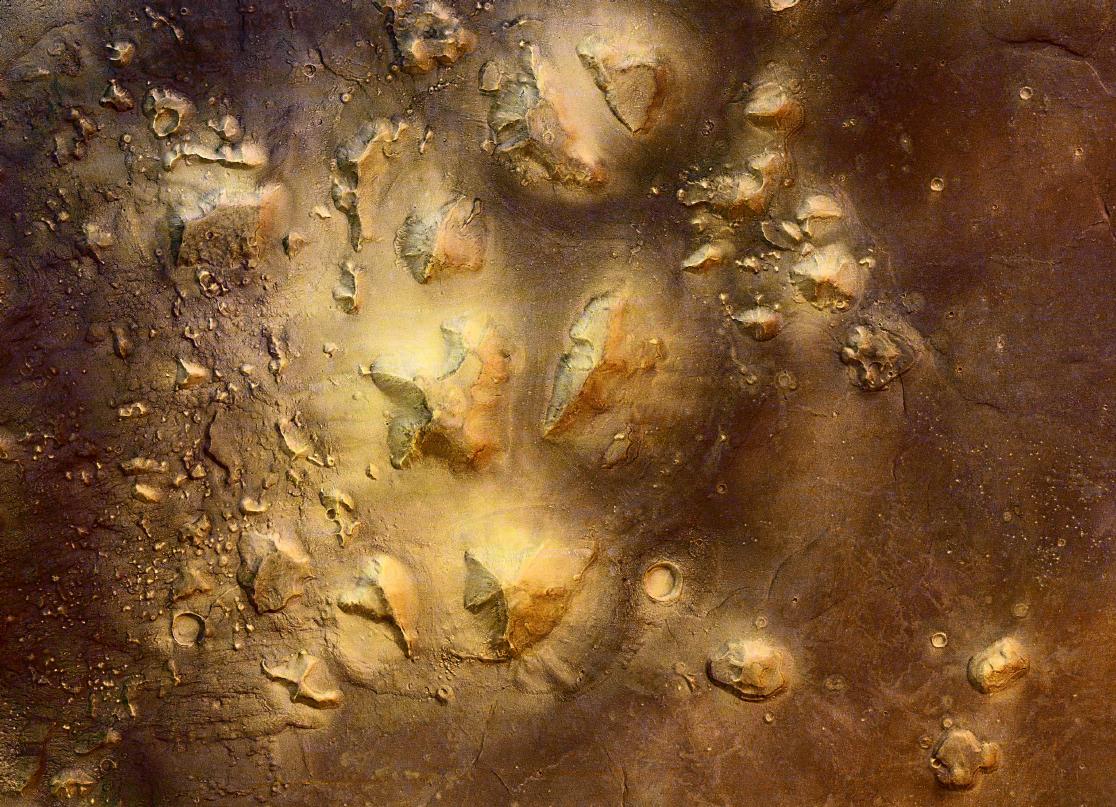

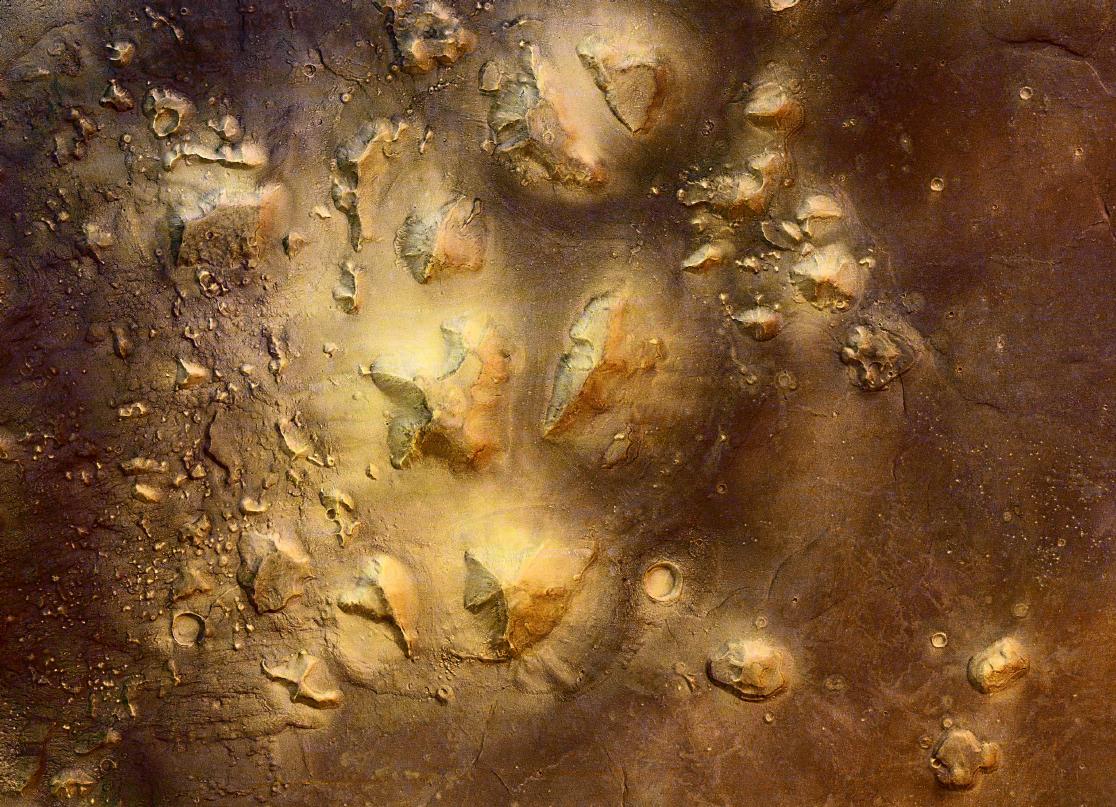

Cydonia

A Mars Express view of the strange Cydonia region, on the Martian

northern Acidalia Planitia lowlands. The many sharply defined

elevated regions have evidently been heavily eroded by water flows.

Cydonia elicted great excitement when the Viking spacecraft first

returned a low-quality image that appeared to show a gigantic,

carved

human face in

the region (in the lower right corner of this image). Later,

high resolution imaging showed

that the "face" was a completely natural formation, although some

enthusiasts continue to argue that Cydonia contains artificial

structures. See

Guide 23 for more discussion of the

"face." Click for a full-resolution version of the image.

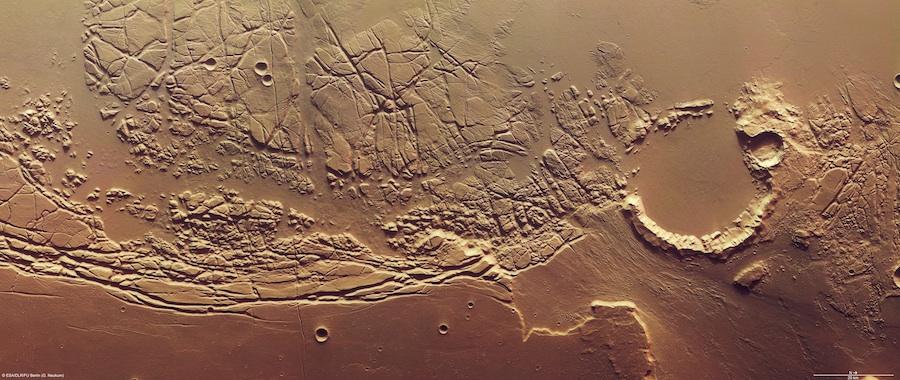

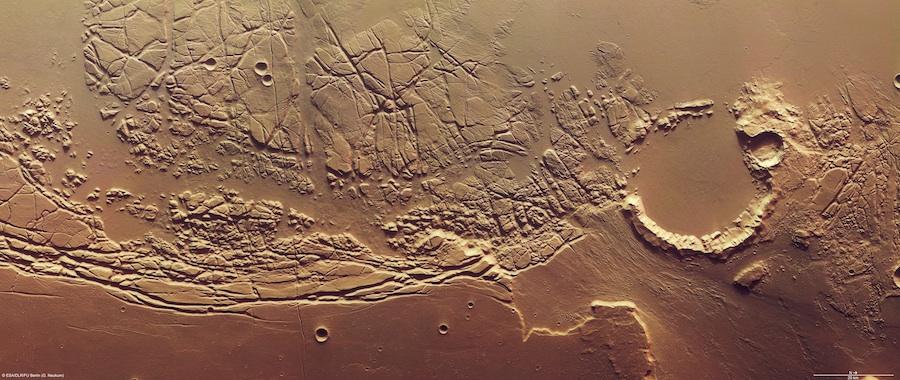

Kasei Valles Boundary

A high-resolution view from the Mars Express orbiter of the boundary

between the large outflow canyon system Kasei Valles (upper area) and

the Lunae Planum plateau (lower left). Kasei Valles runs northward

from near Valles Marineris and feeds into the the northern

lowlands/ocean basin. North is to the right in the image. The jumbled

terrain was scoured by gigantic water flows in the past, which also

eroded the upper wall of the 22-mile diameter crater at the right of

the image. The volume of water involved was several thousand times the

flow of the Amazon River. Click for a much enlarged image.

Kasei Valles Boundary With Altitude Coding

The same region shown above but with pseudocolor coding for altitude.

The coding is shown in the upper right. Click for a much enlarged

image.

Acidalia Planitia Channels

A high-resolution view from the Mars Express orbiter of a region about

600 miles northeast of the previous image. This shows the channels

feeding into the northern Acidalia Planitia lowlands (below) from the

Tempe Terra plateau (above). Color-coded for altitude; blue indicates

the lowest altitude. Resolution is 15-m per pixel. Note the

older craters that have been filled in/submerged by wind or

water-borne material.

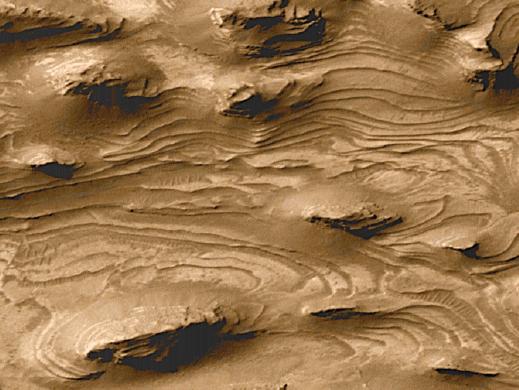

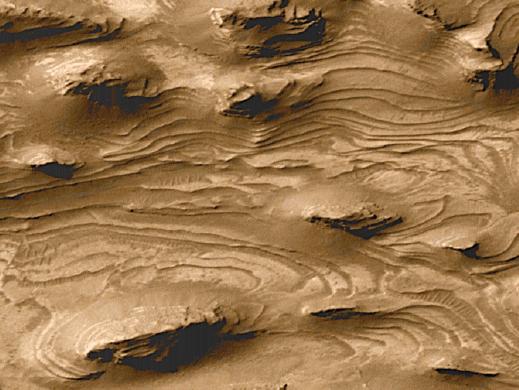

Water on Mars: Sedimentary Layering

This image from MGS shows a part of the floor of the Candor Chasma

canyon, about 0.5 mile wide. It contains a number of layers of

material, each about 30 feet

thick.

Here

and

here

are similar layered regions. On Earth, deposits like this form from

sedimentary deposits at the bottom of a lake. This is strong

circumstantial evidence for water on Mars at an earlier time. If

these are sediments, they might contain fossils of ancient Martian

lifeforms. Similar features might be produced by lava flows or

windblown dust deposits, but their ubiquity on Mars suggests water is

involved. Click for a full-scale version. [Image by Malin Space

Science Systems]

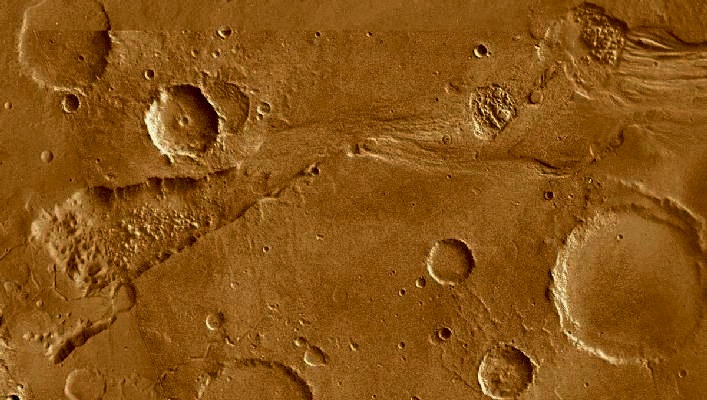

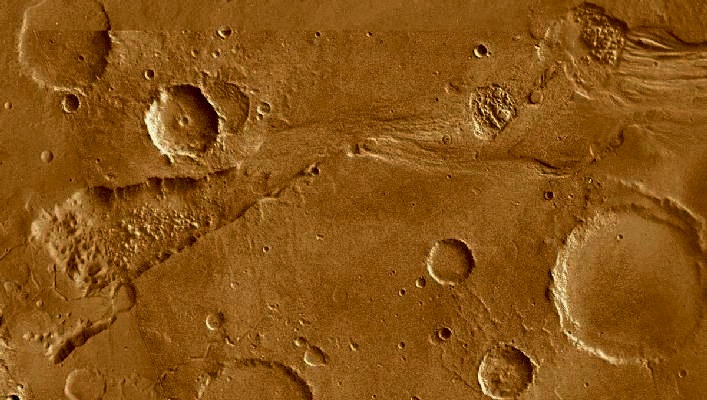

Water on Mars: Ravi Vallis

A Viking mosaic of the Ravi Vallis channel. Unlike

Valles Marineris, this channel was carved by water. The region shown

is about 225 mi long.

Like many other channels that empty into the northern plains of Mars,

Ravi Vallis originates in a region of collapsed and disrupted

("chaotic") terrain within the planet's older, cratered highlands.

Structures in these channels indicate that they were carved by liquid

water moving at high flow rates (up to 1000's of times the outflow of

the Amazon River). The abrupt beginning of the channel, with no

apparent tributaries, suggests that the water was released under great

pressure from beneath a confining layer of frozen ground. As this

water was released and flowed away, the overlying surface collapsed,

producing the disruption and subsidence shown here. Three such regions

of chaotic collapsed material are seen in this image, connected by a

channel whose floor was scoured by the flowing water. The flow in this

channel was from west to east (left to right). This channel ultimately

links up with a system of channels that flowed northward into Chryse

Basin. [Image & caption: LPI]

Water on Mars: Runoff Channels

These networks of smaller tributaries leading to larger channels resemble

those produced by ground water flow (as opposed to rain) on Earth. Click

for enlargement.

[Image by Calvin J. Hamilton.]

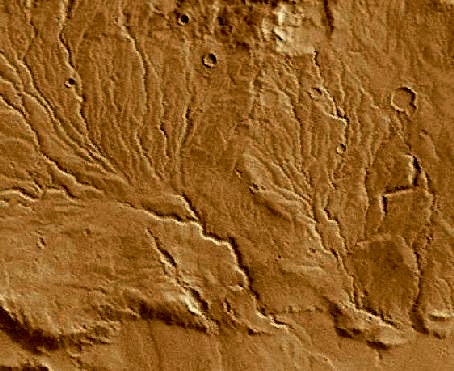

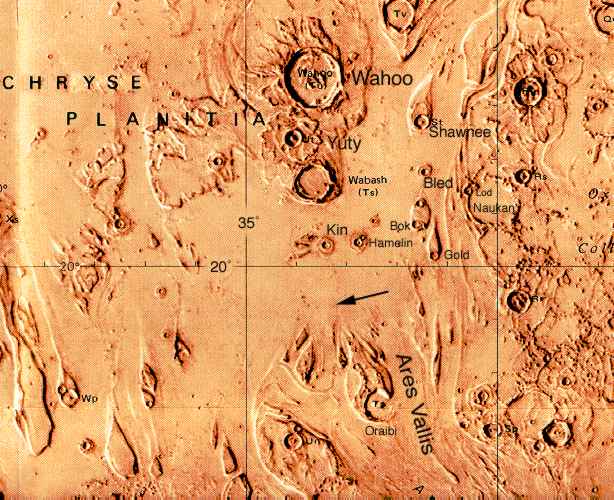

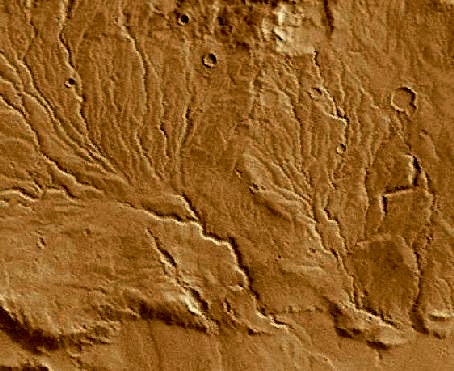

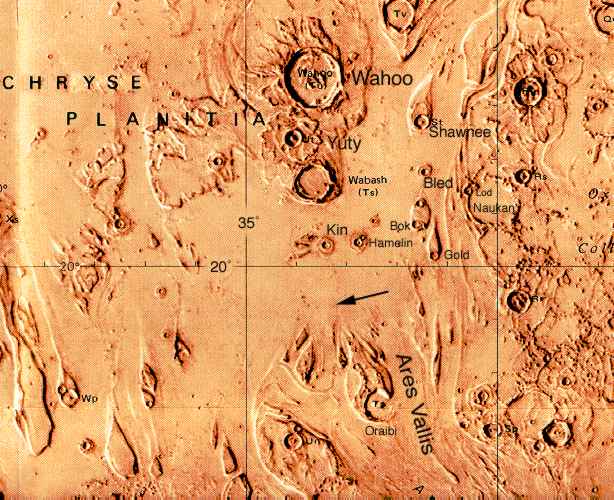

Water on Mars: Ares Vallis, The Pathfinder Site

A plain showing prominent scars of catastrophic flooding, probably 1-3

Byr ago. This is an artist's rendering, based on a

Viking orbiter mosaic, with

identifications added for the more prominent features. The arrow shows the

initial landing zone targeted for the Mars Pathfinder in July 1997.

Note the "Wahoo" crater(!) [Painting by NASA. Images from

NSSDC.]

Water on Mars: Frozen Lake in Crater

This image of a crater in near the Martian North Pole was taken

by the High Resolution Stereo Camera on the Mars Express orbiter.

It shows a large lake of water ice. The temperature when the image

was taken was above the sublimation temperature of carbon dioxide

("dry") ice, so the material must be water ice. The lake is about

10 km (33,000 ft) across.

Water on Mars: Hematite "Blueberries"

The Mars Exploration Rover "Opportunity" took this close up of the

surface near its landing site showing thousands of tiny spherules

called "blueberries" because of their blueish tint in false-color

images. They contain hematite, an iron-oxide mineral precipitated

from water. Such "concretions" are also found on Earth.

Water on Mars: Ancient Ocean Beds?

This is a MOLA elevation map of the north polar hemisphere, with the

outline of the US added for scale. It shows a huge depression which

has many characteristics expected for an ancient ocean bed. Its

border is level in elevation, like a coastline; terraces run parallel

to the coastline; its floor is smooth and relatively flat, suggesting

sedimentation; it is "fed" by channels running from south to north.

Its volume is consistent with other estimates of the total volume of

water on Mars. [Image by MOLA Team]

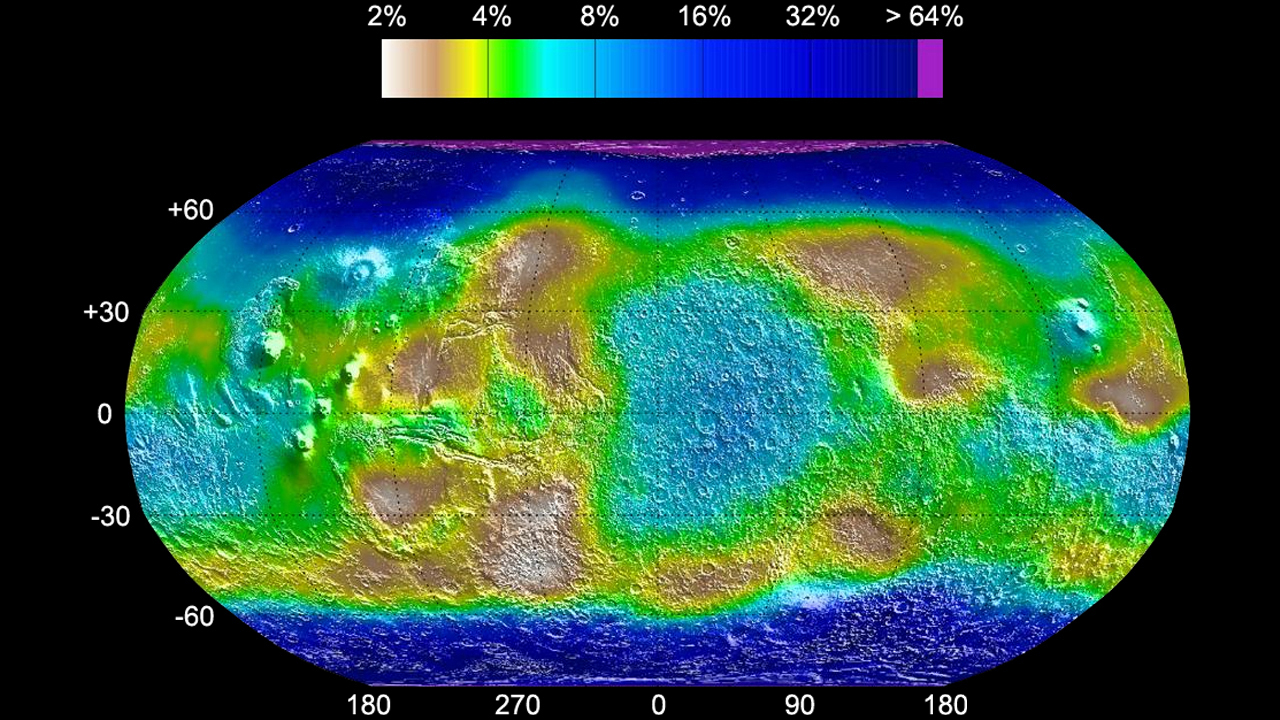

Water on Mars: Distribution of Water Molecules

This is a map of the fractional content of water molecules in the

upper 1-meter or so of the Martian surface. It was obtained by the

Gamma Ray Spectrometer experiment on the orbiting Mars Odyssey

spacecraft. This instrument detects gamma rays emitted by hydrogen

atoms on the surface after they are activated by

penetrating cosmic

rays. Some regions of the surface are quite dry, but most contain

significant water, and both poles are rich in water molecules. The

gamma-ray technique allows other individual elements to be mapped as

well, including silicon, chlorine, and iron. [Image from Mars

Odyssey]

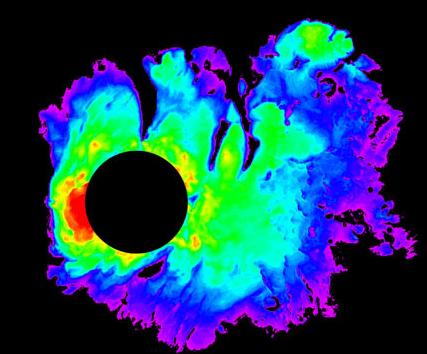

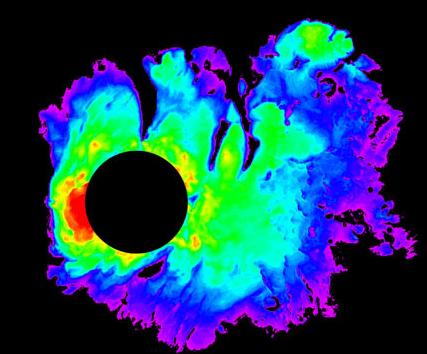

Water on Mars: Ice Under the South Pole

This picture shows a map made with the MARSIS ground-penetrating radar

instrument on the Mars Express orbiter (March 2007). The radar is

reflected from regions up to 13,000 feet below the surface of Mars'

South Pole, and the image shows the thickness of the layers of water

ice. The black circle is an area without data. This is the largest

water reservoir yet detected on Mars. If distributed uniformly over

the Martian surface, it would cover the planet 36 feet deep in liquid

water. But the flood plains seen on the surface suggest that there

was over 10 times as much water originally present on Mars. [Image

from Mars Express]

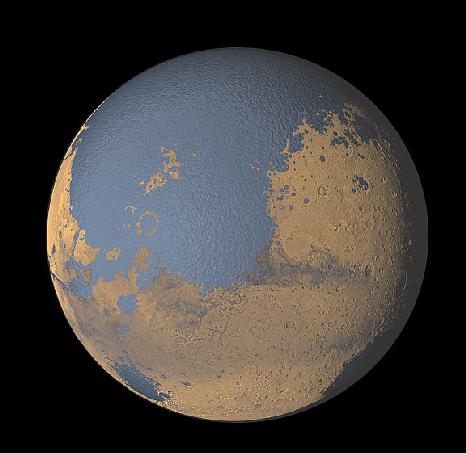

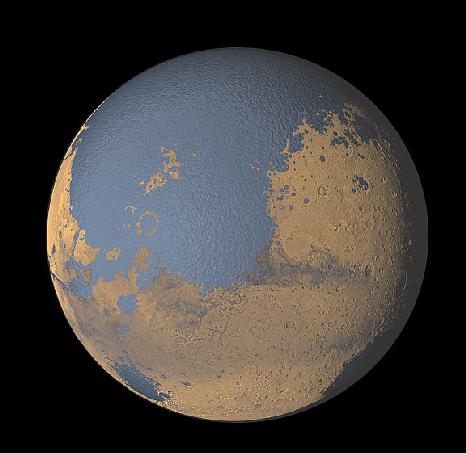

Water on Mars: Volume

Spectroscopic measurements of molecular hydrogen in the Martian

atmosphere with the FUSE satellite provide an estimate of the total

volume of water once present on Mars: the equivalent of a global

Martian ocean some 4000 feet deep. The image above is an artist's

concept of what Mars might have looked like when all its low-lying

areas were filled with water.

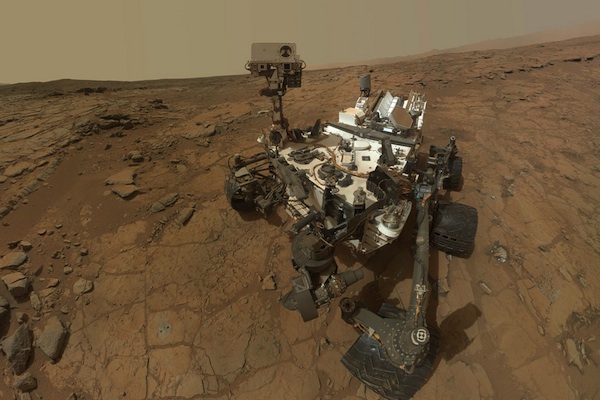

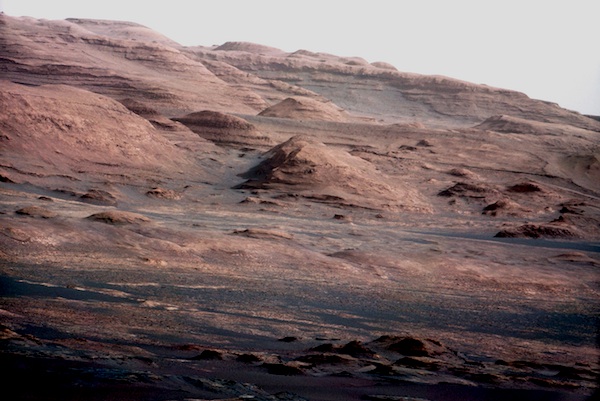

Curiosity on Mars

At the left is a self-portrait of "Curiosity," the rover of

NASA's

Mars Science Lander

mission, at it looked on the surface of Mars in February 2013. It

carried the most sophisticated set of geophysical analysis instruments

sent to another planet up to that time. In a

complex

landing

sequence Curiosity was placed within 1.5 miles of its intended

landing site in Gale Crater on August 6, 2012. This 96-mile diameter

crater contains a large central mountain (Aeolis Mons or "Mt. Sharp")

composed of sedimentary rock. At right is a telephoto view of Aeolis

Mons taken by Curiosity, showing its layered structure. Curiosity is

exploring the flanks of the mountain. Click on the images for

enlargements. To follow Curiosity's progress, check

the

Curiosity Rover mission site

at JPL.

Last modified

December 2025 by rwo

Original text copyright © 1998-2025 Robert W. O'Connell.

All rights reserved. These notes are intended for the private,

noncommercial use of students enrolled in Astronomy 1210 at the

University of Virginia.

Return to Study Guide 16

Return to Study Guide 16

Guide Index

Guide Index