ASTR 511 (O'Connell) Lecture Notes

PRINCIPAL UVOIR TELESCOPES

Summit of Mauna Kea, Hawaii

Estonian translationI. INTRODUCTION

The human imagination has never been a match for the universe. That is why astronomy, more than any other science, has been regularly revolutionized by new observational discoveries. Since 1610, these have depended on telescopes. When telescope technology developed slowly, as in the early 19th century, progress was slow. When technology surged, as in the late 20th century, progress was explosive. This page surveys the principal UVOIR telescopes available in this decade together with a review of the milestones of the last 100 years. A hallmark of the major telescopes in this era is the remarkable variety of clever innovations, many of which have even more distant historical roots. There is very little in current telescope design that was not thought of long ago, though converting good ideas into realizable technologies is a different matter. A key historical lesson is that to build an instrument at the frontier of performance is always costly in terms of brains and money. Thus, progress has coupled new technology, visionary astronomical pioneers, and the generosity of wealthy private donors or the financial strength of governments. Note: we will not discuss telescope optics except briefly in this course (see this page.) That topic and the detailed properties of detectors and instruments are covered in Astronomy 512.

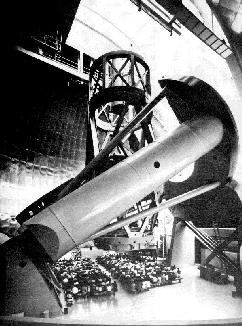

The Mt. Wilson 100-in Reflector

II. AMERICAN OBSERVATORIES 1880-1970

A. BACKGROUND

Optical and mechanical technology in the last few decades of the 19th century had advanced to the point that the construction of large telescopes was feasible. Success with large telescopes demands that a large set of disparate requirements be met simultaneously: quality glass for optical elements, high precision shaping/polishing of optical surfaces, precision mechanical support systems, excellent control systems, excellent instrumentation, and good observing sites. Any such project is a major engineering undertaking. Most of the large telescopes through 1960 were associated with universities. They were costly and required substantial private donations. Because of an abundance of industrial expertise, excellent observing sites, and wealthy contributors, the US became the world's leader in building large telescopes. Refractors vs Reflectors:

The large telescopes of the late 1800's were mainly refractors. These were

simple optically and featured good stability for astrometry, for

instance. Through the mid-1800's, most reflectors had used metal

mirrors and were of generally poor optical quality. However, the invention

of high reflectivity thin metallic coatings for glass (initially silver)

around 1850 made possible the use of glass mirrors. These were immediately

competitive with refractors in terms of quality.

This, together with a host of other reasons dictated that instruments

larger than the Yerkes 40-in refractor were all reflectors:

|

| To maintain a good image, a single reflecting surface must be figured to within 1/4 wavelength of its intended design. For optical telescopes, this is 10-5 cm---very demanding. Good polishing/test techniques capable of reaching this precision were not developed until the late 19th century. When there are several reflecting surfaces, the tolerances must be tighter. Specifications for state-of-the-art telescopes are for 1/10-1/20 wave optics. The most precise large mirror yet made was the HST 2.4-m, which was figured to about 1/50 wave (of its test wavelength of 6328 Å). Scale comparison: if a 320-in (8-m) diameter telescope mirror were scaled up to the size of the continental United States, i.e. about 3000 miles diameter, then the maximum size of a ripple allowed in its polishing would be less than 2 inches! [You should be asking yourself how it is possible to determine the figure of a large mirror to that precision without the use of very expensive metrology equipment.] |

B. IMPORTANT MILESTONES

- Leander McCormick Observatory 26-in refractor (UVa, 1885). Largest in the US when dedicated. Optics figured by Alvan Clark; 32-ft length.

- Lick Observatory 36-in refractor (U Calif., 1888), the first mountaintop observatory (4200 ft). Optics figured by Alvan Clark; 58-ft length.

- The Yerkes Observatory 40-in refractor (Univ. of Chicago, 1897). The largest refractor ever built (picture above right). Lens originally intended by USC for a Mount Wilson site. Optics figured by Alvan Clark; f/19; 63-ft length.

- The Mt. Wilson 60-in

reflector (1908), the first major reflector in the US. Fork mount. Optics

figured by George W. Ritchey. f/5 Newtonian, bent-Cassegrain. First

to have a coude focus. Early optical coatings were silver. Mt. Wilson

Observatory was operated by the Carnegie Institution.

- The Mount Wilson 100-in reflector (1917), the most important telescope of the 20th century (photo at beginning of this section). Optical figuring by George Ritchey (with reluctance, because of bubbles in the mirror blank below the surface). English yoke mount on mercury flotation bearings (exclusion zone near pole). Three main foci: Newtonian (f/5; reachable by dome-mounted platform), bent-Cassegrain, and coude.

- The Palomar Observatory 200-in (5-m) reflector (Caltech, 1948), the largest working telescope until 1992. The 20-year process of planning & building the 200-in is described in a photo-history here. Placed at Palomar because, even by 1920, Mt. Wilson was suffering serious light pollution from Los Angeles. Above right is a photo of the 200-in dedication in 1948. A diagram of the telescope is shown here. Yoke-mounted, with a horseshoe-shaped, oil pressure supported north bearing. First telescope with a prime-focus (f/3.3) "cage" capable of carrying an astronomer. Other foci: Cassegrain, coude.

- At the urging of Fritz Zwicky, among others, Caltech commissioned the 48-in Schmidt telescope as a wide-field survey instrument to support the 200-in. Based on the design of Bernhard Schmidt this catadioptric telescope uses a spherical mirror together with a thin refractive corrector lens to eliminate spherical aberration over a wide field of view (6o diameter in this case). The 14-in square focal plane is inside the body of the telescope; it is convex and required that photographic plates be curved under pressure to match. The 48-in Schmidt made the multiband photographic "POSS" surveys and today, with the substitution of a large-format CCD mosaic camera, is undertaking the Zwicky Transient Survey.

- In the 1970's, NOAO developed a 4-m telescope design based on the 200-in, and this has been reproduced, more or less closely, in multiple versions, sizes 3.5-4.2m, around the world (e.g. KPNO 4-m, CTIO 4-m, AAT, CFHT).

Polished & coated 8-m (315-in) mirror for the Gemini project, 1999.

III. NEW TECHNOLOGIES 1970-2020

Telescope technologies steadily improved throughout the first half of the 20th century, with much progress in mechanical design (e.g. the oil pressure bearing of the 200-in), structural materials, optical figuring, electrical control systems (e.g. analog computers), and astronomical instruments to attach to telescopes. However, until about 1975, big telescope design was still based largely on the concepts used for the Mt. Wilson and Palomar reflectors (designed 1900-30). Unfortunately, the cost of extending such designs to sizes larger than 200-in was prohibitive. For a given design, cost scales roughly as the mass of the telescope or the cube of the diameter. In the early 1980's a series of innovations was introduced that made yet larger telescopes affordable, mainly by reducing the total weight, including the dome, per unit optical collecting area. These included:

|

|

Site selection was recognized as critical. For best

transparency at infrared wavelengths, high, dry sites, over 8,000

ft, became preferred. The summit of Mauna Kea, on the big island of Hawaii, is at 13,800 feet and

is the premier telescope site in the northern hemisphere.

Needless to say, good telescope sites must be as distant as possible

from sources of

artificial light pollution, a growing worldwide

problem.

The financing yo-yo:

|

The European Southern Observatory Very Large Telescope.

IV. STATE OF THE ART TELESCOPES

As of 2018, there were 16 ground-based telescopes operating with diameters of 6.5-m or larger. A list with links is available here, and a nice graphical comparison of the collecting areas of large telescopes through 2025 is shown here.- The European Southern Observatory Very Large Telescope: four 8.2-m telescopes on a very dry site in northern Chile, now has the largest total collecting area in the world (211 square meters), although the telescopes are normally operated separately. The monolithic primary mirrors are spin-cast Schott Zerodur (very low CTE) in a meniscus shape (46:1 aspect ratio). Shape is actively controlled with 150 actuators. The four telescopes can be combined to operate as an interferometer and have well developed adaptive optics (AO) systems.

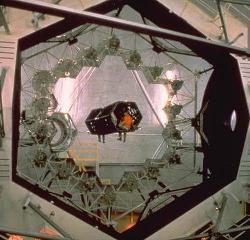

- The Keck Observatory

-

Twin 10-m diameter telescopes based on a

segmented primary design (picture at

right). Each contains 36 stress-polished and cut 36-in hexagonal mirror

segments, with a total collecting area of 76 square meters and

a focal ratio of 1.75. The optical system is a Ritchey-Chretien

design.

The Keck mirror figure control system is a remarkable technical

achievement, although image quality is not quite as good as for a

monolithic mirror. With its AO system, Keck can deliver a resolution of 0.05 arcsec at

IR wavelengths. (Ground-based seeing becomes worse

at shorter wavelengths, and AO systems do not work well at

wavelengths below 1 µ or over fields larger than ~30 arcsec.)

Principal foci: Naysmith, Cassegrain. Interferometric combination of

beams from the two telescopes was implemented until 2012.

- Gran Telescopio Canarias, on La Palma island, is operated by a consortium led by Spain and Mexico. It has a segmented-primary design similar to each Keck telescope but with slightly larger segments and a collecting area of 78 square meters.

- Hobby-Eberly Telescope, operated by a consortium led by UTex and PennSt. An "optical Arecibo" with a large (9.2-m) mirror made of spherical segments. Fixed in altitude (55 degrees). Less successful figure control than Keck. Intended for spectroscopy of faint sources. A twin was constructed in South Africa (SALT).

- The Gemini Observatories: two telescopes (Mauna Kea, Hawaii & Paranal, Chile) operated by an international consortium, including the US. 8.1-m, 20-cm thick Corning ULE meniscus mirrors with 120 figure control actuators. IR-optimized, using silver coatings. Total operations cost, about $45,000 per night (2015).

- Subaru: 8.2-m optical/IR telescope on Mauna Kea similar to Gemini; operated by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan..

- 6.5-meter class: MMT (Mt. Hopkins, AZ), Magellan I, Magellan II (Las Campanas, Chile). All use Arizona Mirror Lab spin-cast, borosilicate mirrors.

- The Hubble Space

Telescope

- First proposed

by Lyman

Spitzer in 1946 but launched in 1990. HST orbits at 300 mi altitude,

where the deleterious effects of the Earth's atmosphere (seeing,

absorption, light emission and scattering) are eliminated. Serviced 5

times by Space Shuttle crews (HST is the only scientific satellite

capable of human servicing). Instrument and spacecraft upgrades were

essential for its long lifetime (30 years to date) and outstanding

performance.

HST has a small (2.4-m) but very high precision mirror in a

conventional Ritchey-Chretien Cassegrain configuration. The primary

mirror shape was inaccurate, however, owing to miscalibrated testing

tools, with an edge about 2 µ too low. This produced large

spherical

aberration (a 38 mm difference in focal length between the inner

and outer mirror areas). That was correctable, however, with small

additional optical elements in each instrument. The first servicing

mission in 1993 carried correcting optics, and HST achieved its design

goals thereafter.

HST carries up to 6 instruments (imagers, spectrographs, interferometers)

covering the band 1100-22500 Å. Owing to its outstanding

instrumental stability, optical precision, excellent pointing, and the

absence of atmospheric blurring, HST has produced the

highest

resolution UV-optical images ever (0.05 arcsec). It has produced the

deepest images yet made, to m ~ 30 mag (4 billion times fainter

than the naked eye limit).

- Special Survey Telescopes: Pan-STARRS (transient or moving sources), Sloan Digital Sky Survey (galaxies, imaging & spectroscopy), 2MASS All-Sky Infrared Survey (stars and galaxies, imaging): see Lecture 15.

The Large Binocular Telescope

V. THE LARGE BINOCULAR TELESCOPE

The Large Binocular Telescope, located on Mt. Graham in southeastern Arizona, currently has the largest collecting area of any single telescope. UVa is a member of the LBT consortium of universities. First binocular light was achieved in March, 2008.- The LBT consists of two 8.4-m diameter mirrors on a single alt-azimuth mount. It carries 6 pairs of focal stations.

- It can operate as two separate telescopes (pointing at the same target), or it can combine the beams of the two mirrors to act as an interferometer yielding the effective optical resolution of a 23-m diameter telescope (about 20 mas at 2 µ). The combined collecting area of the two mirrors is 111 square meters, corresponding to a single 11.8-meter (460-in) diameter mirror.

- Spin-cast, honeycombed, lightweight borosilicate mirrors, with active ventilation thermal control system.

- Active control of secondary mirror for compensation of mirror figure changes and suppression of atmospheric seeing. Multiple laser guide-star adaptive optics system.

- Click here for pictures of LBT construction.

VI. THE NEXT GENERATION

Two very large telescopes based on the segmented-mirror concept

of Keck have been designed:

the

Thirty Meter Telescope

and the

European

Extremely Large Telescope (39-meters or 1530-in). The ELT is now

under construction in Chile, but the TMT is embroiled in a dispute

over environmental and cultural impacts at its preferred Mauna Kea

site. The

Giant Magellan Telescope

(at right), also

under construction in Chile, is a multiple-mirror design with

7 8.4-meter spin-cast mirrors and an equivalent collecting area

of a single 22-meter mirror. The combined primary mirror

surface is parabolic, and the six off-axis segments are

asymmetrically aspheric and difficult to figure.

Another large telescope with a very different design and operations

mode is the Rubin Observatory Large Synoptic Survey

Telescope. To achieve a wide field of view (3.5o) it

employs a unique 3-mirror

design in which the primary and tertiary mirrors have been figured

on a single piece of spin-cast glass 8.4-meters in diameter. The

telescope is intended to repeatedly image the entire usable sky every

three nights, searching for transient or moving targets while building

up an ultra-deep combined image of the sky. Continuous output from

its 189 imaging CCDs will generate an unprecedented data volume (15

TB/night). Under construction in Chile, LSST should begin full

operations in 2022.

The James Webb Space

Telescope is the follow-on to HST. It features a 6.5-m diameter

primary mirror (a 25 square meter collecting area, 5.5 times that of

HST) composed of 18 hexagonal segments that must be deployed on-orbit.

JWST carries four imaging and spectroscopic instruments and is

optimized for the near-infrared (1-30 µ). It will achieve the

same spatial resolution in the NIR as HST does in the UV-optical band.

A large sunshield permits a low overall structural operating

temperature through cooling to space. JWST will orbit around the

Earth-Sun L2 point, about 900,000 km from Earth.

Instrument and main optics testing has been completed, but integration

of the telescope with its spacecraft encountered quality-control

problems in 2018. Launch is now scheduled for 2021.

Two very large telescopes based on the segmented-mirror concept

of Keck have been designed:

the

Thirty Meter Telescope

and the

European

Extremely Large Telescope (39-meters or 1530-in). The ELT is now

under construction in Chile, but the TMT is embroiled in a dispute

over environmental and cultural impacts at its preferred Mauna Kea

site. The

Giant Magellan Telescope

(at right), also

under construction in Chile, is a multiple-mirror design with

7 8.4-meter spin-cast mirrors and an equivalent collecting area

of a single 22-meter mirror. The combined primary mirror

surface is parabolic, and the six off-axis segments are

asymmetrically aspheric and difficult to figure.

Another large telescope with a very different design and operations

mode is the Rubin Observatory Large Synoptic Survey

Telescope. To achieve a wide field of view (3.5o) it

employs a unique 3-mirror

design in which the primary and tertiary mirrors have been figured

on a single piece of spin-cast glass 8.4-meters in diameter. The

telescope is intended to repeatedly image the entire usable sky every

three nights, searching for transient or moving targets while building

up an ultra-deep combined image of the sky. Continuous output from

its 189 imaging CCDs will generate an unprecedented data volume (15

TB/night). Under construction in Chile, LSST should begin full

operations in 2022.

The James Webb Space

Telescope is the follow-on to HST. It features a 6.5-m diameter

primary mirror (a 25 square meter collecting area, 5.5 times that of

HST) composed of 18 hexagonal segments that must be deployed on-orbit.

JWST carries four imaging and spectroscopic instruments and is

optimized for the near-infrared (1-30 µ). It will achieve the

same spatial resolution in the NIR as HST does in the UV-optical band.

A large sunshield permits a low overall structural operating

temperature through cooling to space. JWST will orbit around the

Earth-Sun L2 point, about 900,000 km from Earth.

Instrument and main optics testing has been completed, but integration

of the telescope with its spacecraft encountered quality-control

problems in 2018. Launch is now scheduled for 2021.

Related pages

Additional References and Web links

- LLM text, Chapter 4

- Henry King, History of the Telescope (through 1950). Well illustrated.

- Allan Sandage, The

First 50 Years at Palomar (ARAA, 37, 445, 1999)

- Daniel Schroeder, Astronomical Optics. Standard textbook

for telescope optical design.

- Pierre Bely, The Design and Construction of Large Optical

Telescopes

- Giant Astronomical

Telescopes for the 21st Century (UCB course with full technical coverage

of large telescope design)

- List

of Largest Optical Telescopes

- List of Telescopes in Orbit

Previous Lecture

Previous Lecture

|

Lecture Index

Lecture Index

|

Next Lecture

Next Lecture

|

Last modified January 2021 by rwo

Images from observatory public sites. Text copyright © 2000-2021 Robert W. O'Connell. All rights reserved. These notes are intended for the private, noncommercial use of students enrolled in Astronomy 511 at the University of Virginia.