ASTR 1210 (O'Connell) Study Guide

4. MOTIONS IN THE SKY

Star trails over the Himalayas in a

2-hour exposure

(Anton Jankovoy).

A. Motions of Bright Objects

The table below lists celestial motions which are easily detectable by someone on the Earth without telescopes.| OBJECT | PERIOD | MOTION |

|---|---|---|

| ALL | Daily ("diurnal") | Rotation Westward |

| SUN | Annual (365 days) | (a) 1 degree/day Eastward* |

| (b) North/South* | ||

| MOON** | Monthly (29 days) | (a) Eastward, N/S* |

| (b) Phase change | ||

| PLANETS (5)** | Months-Years | Generally Eastward, but with Westward loops* |

-

*Except for the diurnal motion, motions are measured with respect to the stars.

The diurnal motion is measured with respect to the local horizon.

**The Moon and the planets move on paths near to, but not identical with, the annual path

of the Sun seen against the stars (the "ecliptic")

-

People are familiar with the motion of the Sun during the day. That

is the most obvious manifestation of the "diurnal motion" of the whole

sky. But the other motions listed are less conspicuous and so slow

that if you aren't a practicing amateur astronomer, you probably

aren't aware of them.

If you're patient for about 20 minutes, you can easily detect the

diurnal wheeling rotation of the whole night sky by comparing

the position of the stars to a fixed foreground object (e.g. a tree).

If you have a digital camera capable of taking exposures longer than a

few minutes, you can readily take images showing star trails,

like the one at the top of the page.

The best way to visualize celestial motions is in a planetarium or

with a good computer sky simulation program. We will use

the Starry Night

simulator in class.

But a faster way to experience the diurnal motion is to view one of

the many excellent time-lapse

videos now available on the Web.

B. Explanation of Motions

In the rest of this guide, we explain these phenomena from a modern scientific perspective. It took many centuries for astronomers to arrive at the correct interpretation described here. Ancient Greek astronomers understood much of this after several hundred years of work, but the knowledge was lost and only rediscovered during the Renaissance, 1300 years later. The key to complete understanding of celestial motions was introduced by the Greeks: mathematics.- The Greeks built mathematical models of the sky based on plane and spherical geometry which they had developed. These reduce a bewildering array of complex phenomena to a much simpler set of mathematical concepts.

- Although it is fashionable today to criticize "reductionism" in science, there would, in fact, have been very little progress in understanding nature (or in converting that understanding to useful technologies) without the tremendous simplifying insights of reductionism.

- Intrinsic motions of the objects themselves with respect to one another

- The motion of the observer, or the platform on which

he/she is standing---in this case, the Earth

-

Because the motions of objects in the sky can be induced by movement

of the observer, we call them apparent motions.

- THE EARTH WE LIVE ON IS A ROUND, TILTED, SPINNING, MOVING PLATFORM.

- Although it is simple to state, it is very difficult for most people to visualize this situation. You instinctively feel yourself to be "upright" and at rest on a flat, stationary Earth, but your instinct here is seriously misleading. This is one of the main reasons it took humans nearly 2000 years to fully accept this explanation, which became the first major discovery of the scientific age (by Copernicus ca. 1540, see Study Guide 6).

- The motions of the Moon and the planets are described on the Lunar Motions page and in Study Guide 5, respectively.

C. Effects of Earth's Shape and Spin

- Earth is a sphere, with a diameter of 7900 miles.

- Half of Earth is always in sunlight; half is always in shadow. We experience night on the shadow side (away from the Sun).

- Daylight = sunlight scattered by the Earth's atmosphere

whenever the Sun is above the horizon. The daylight glare overwhelms

the light of the planets and stars, so we cannot see them (though they

are, of course, always there).

- The glare rapidly declines as the Sun

dips below the horizon ("dusk"). "Civil twilight," the point at which

sunlight is just barely perceptible, occurs when the Sun is 6 degrees

below the horizon.

- Earth spins on its axis with respect to the stars once in

23 hours, 56 minutes (one "sidereal day").

-

This causes the

apparent diurnal rotation of the whole sky. (The universe is not

moving around the Earth once per day.)

If the Earth were assumed not to be spinning, then the

diurnal movement of the sky would necessarily imply that it was at

the center of the universe. This was the first assumption

discarded by Copernicus on his way to

rejection of the ancient "geocentric" cosmologies.

- Earth's spin is counterclockwise (eastward) as seen from above

Earth's N pole; this means that the apparent rotation of the sky seen

from Earth's surface is westward.

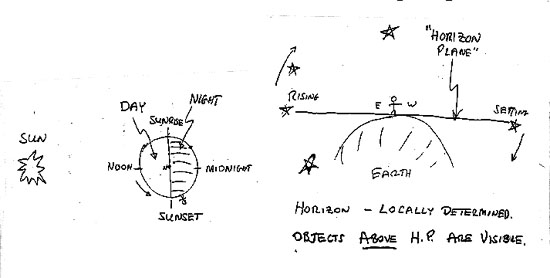

- The left-hand panel of diagram above shows Earth viewed from above its

North Pole. The Earth rotates counterclockwise in this diagram,

carrying observers with it.

- The positions where observers on the equator are experiencing sunrise, noon, sunset, and midnight are marked. Mean local times of day corresponding to these points are 6 AM, 12 noon, 6 PM, and 12 midnight, respectively.

- The right hand panel shows the local "horizon plane,"

which is the plane "tangent" to Earth at your location. You can see

(in principle) objects above the plane but not below it.

- Note that half of the entire "celestial sphere" (see Study Guide 3) is always above your horizon plane. However, because the Earth is spherical, the horizon plane (and the visible hemisphere) is different at each location on the Earth's surface.

- The horizon plane sweeps across the sky as Earth spins. Astronomical objects appear to move in the opposite direction (shown by the arrows in the figure). Objects rise over the eastern horizon and set toward the western horizon.

- The left-hand panel of diagram above shows Earth viewed from above its

North Pole. The Earth rotates counterclockwise in this diagram,

carrying observers with it.

- By combining the concept of the horizon plane with the definition of local time in the left-hand panel, you can visualize what parts of the sky are observable at any given time at a given location on the Earth.

D. Effects of Earth's Motion in Orbit

- Earth is a planet moving in orbit around the Sun

- Its orbit is nearly circular (the distance to the Sun varies only 3.4%), with a mean radius of 150,000,000 km or 93,000,000 miles. The mean radius is defined to be the Astronomical Unit (AU).

- Its orbit lies in a plane called the "ecliptic" plane. Seen face-on, the orbit is technically an ellipse but deviates only slightly from a circle. Seen edge-on, the orbit is a thin line.

- Earth orbits the Sun in 365.25 days (one year) moving at ~66,000 mph. Its motion is counterclockwise as seen from above the north pole.

- Stars visible at night are those "opposite" the Sun. See the two

figures above. The night side of Earth is that opposite the Sun. So,

in May, the constellation Scorpio will be prominent in the night sky,

while in November, it lies in the direction of the Sun and therefore

is not visible because of the daytime atmospheric glare.

- Warning! the drawings in this guide,

and most others you will see in this course either in the text or in

class, are grossly distorted and not to scale! Don't take them

literally. In contrast to the drawing above of the Earth's orbit, the

real orbit is 100 times the diameter of the Sun; the Earth itself is

100 times smaller than the Sun; the stars are vastly distant from the

Earth's orbit; and the stars in a given constellation are not

necessarily near one another in space.

- Obviously, no one could produce or sensibly view a figure like this drawn to actual scale.

- We are viewing Earth's orbit here from an inclination such that it looks highly elliptical, whereas it is nearly circular seen face-on.

- Warning! the drawings in this guide,

and most others you will see in this course either in the text or in

class, are grossly distorted and not to scale! Don't take them

literally. In contrast to the drawing above of the Earth's orbit, the

real orbit is 100 times the diameter of the Sun; the Earth itself is

100 times smaller than the Sun; the stars are vastly distant from the

Earth's orbit; and the stars in a given constellation are not

necessarily near one another in space.

- The Earth's motion around the Sun is counterclockwise in

the drawings above (drawn from a viewpoint that is north of the Earth's

orbital plane), so that in August, the Earth's position would be

nearest the drawing of Capricornus in the diagram.

- Earth's orbital motion produces an apparent eastward "reflex motion" of the Sun in the sky against the stellar reference frame as seen from the Earth.

- From the drawings, we find that the Sun in November would be seen in projection in the direction of Libra, while in December, 30 days later, the Earth has moved such that the Sun is seen in projection against Scorpio, which is approximately 30 degrees east of Libra. Therefore, the average "reflex motion" of the Sun with respect to the stars as seen from Earth is 1 degree per day eastward.

- The ecliptic path:

- The Sun's annual path seen from the moving Earth against the stars is called the "ecliptic path." This is simply the projection of the ecliptic plane on the celestial sphere.

- The "Zodiac" is the set of constellations through which the ecliptic path passes. Those are the only constellations which have been illustrated in the drawings above. Of course, there are 76 other constellations not shown.

- The only astronomical significance of the 12 Zodiacal constellations, therefore, is accidental: they happen to lie on the projection of the plane of the Earth's orbit. They are not the largest, brightest, or most prominent constellations (in fact a number are quite inconspicuous).

- Practice exam question: which Zodiacal constellation will be best seen at midnight in August?

- "Solar" vs. "sidereal" days: The daily motion of the Earth in its

orbit means that the Earth must spin a little more than once

on its axis to bring the Sun back to the point of local "noon" (i.e.

halfway between rise and set). The extra amount is 4 minutes, on

average.

- The effect of Earth's motion during one sidereal day is illustrated here.

- This accounts for the difference between the sidereal spin

period of the Earth (23 hours, 56 min) and the average

elapsed time between successive noons (24 hours, the

"solar day"). Our ordinary clocks, of course, are set such that the

time between successive noons is defined to be 24 hours. But

the stars come back to the same position in the sky as seen from

Earth 4 minutes earlier each day. This means, for instance,

that the stars you see at 11 PM in a given month have the same

location with respect to the horizon as they did at 9 PM one month

earlier or 7 PM two months earlier.

E. Tilt of Earth's Axis

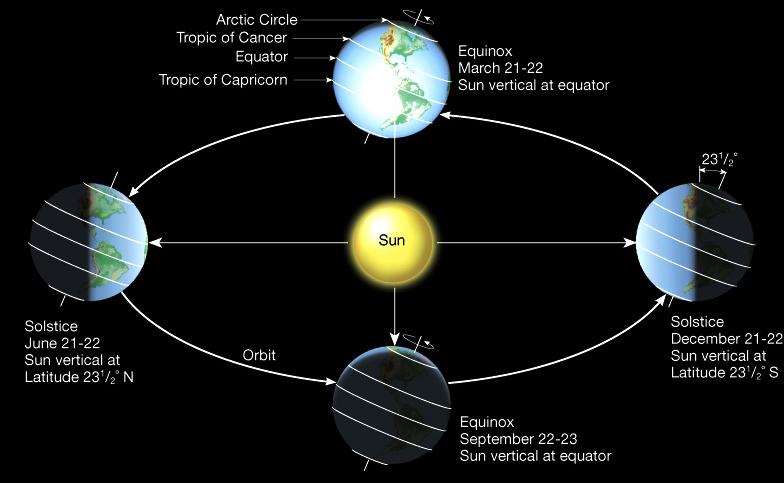

- The polar rotation axis of the Earth is not perpendicular to

its orbital plane. It is tilted by 23.5 degrees from the vertical,

or, equivalently, it is tilted 66.5 degrees out of the plane. See figure

below (again, exaggerated for clarity):

- The rotation axis is fixed in direction with respect to the

stars, not with respect to the Sun. As Earth

orbits the Sun, the axis continues to point in the same direction

in 3D space. This implies that the north pole is sometimes

"tilted toward" the Sun, sometimes "tilted away." In the illustration

above, the North Pole is shown at its maximum tilt away from the Sun

(assuming the North Pole is at the top).

-

The fixed axis direction of the Earth during a year is illustrated

in the drawing in Section F below.

- This, in turn, implies that the Sun, as viewed from the Earth,

will appear to move north and south of the celestial equator

through the year by a maximum of + or - 23.5 degrees. In the drawing

above the Earth is situated such that the Sun will be seen at its most

southerly position during the year.

-

The total amplitude of the Sun's N/S swing across the celestial

equator is 2 x 23.5 = 47 degrees.

- Equivalently, the ecliptic path is inclined 23.5

degrees to the celestial equator. The following diagram shows

the ecliptic and the equator on the celestial sphere (see Guide 3 for the definition of the celestial

sphere).

- The ecliptic crosses the celestial equator at two points

called equinoxes.

- When the Sun is at an equinox, night and day are each 12 hours long at all latitudes. The "Vernal Equinox" in the northern hemisphere occurs around March 21, while the "Autumnal Equinox" occurs around September 21.

- The Sun is at its greatest distance from the equator (23.5 degrees) at the solstices ("sun stationary"), which are approximately June 21 and Dec 21. At these times, one hemisphere experiences its longest day, the other its shortest.

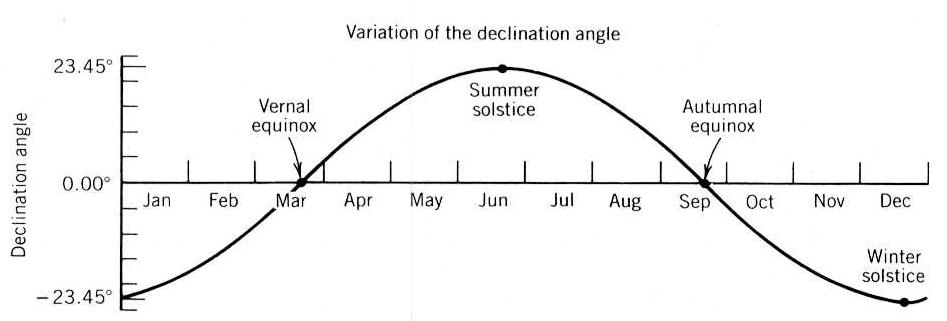

- The diagram below shows the position of the Sun on the celestial sphere with respect to the equator plotted against date. The longest and shortest days in the northern hemisphere occur at the June and December solstices, respectively. (The labeling in the diagram is for the northern hemisphere; the seasons are reversed in the southern hemisphere.)

F. Astronomical Effects on the Weather

- The Sun's north/south distance from the celestial equator

determines:

- The number of hours of daylight at a given latitude and

- The angle at which sunlight strikes Earth's surface at a given latitude. More energy is incident per unit area per second on the surface the closer are the rays to perpendicular to the surface.

- The Sun's angular distance from the celestial equator thus determines insolation, or the amount of solar energy deposited on a given area of the Earth's surface during 24 hours at a given latitude.

- This differential heating is responsible for the seasons. The "official" beginning dates of spring, summer, autumn, and winter correspond to the Vernal Equinox, Summer Solstice, Autumnal Equinox, and Winter Solstice, respectively.

-

The diagram below shows how the hours of daylight (represented by

the length of the white lines on the illuminated half of the Earth)

and the solar angle of incidence at different latitudes correlate with

the date. A close-up of the situation is shown here.

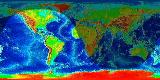

- The change in the geographic shadow distribution caused by the

tilt is quite dramatic (even though the shadow always covers exactly

one half of the Earth's surface). Below are two images of the way the

shadow is distributed at two different times of year. The Earth's

surface moves eastward (toward the right in the diagrams) through the

shadow as the Earth rotates. You can immediately tell from the image

which latitudes are receiving more sunlight in a 24 hour period.

Click on the thumbnails for an expanded view.

2 PM EDT August 1 2 PM EST December 1 -

Here

is a nice timelapse video compilation of images from space of the

Earth's surface at the Autumnal Equinox in 2013.

Here

is a nice timelapse video compilation of images from space of the

Earth's surface at the Autumnal Equinox in 2013.

- Therefore, the seasons are caused by the tilt of the Earth's

pole to its orbital plane, not its distance from the Sun.

-

If the seasons were a distance effect, winter, for instance, would

occur simultaneously in both the southern and northern

hemispheres. But instead, the seasons differ by 6 months in the two

hemispheres.

There is a small annual change in the distance of

the Earth from the Sun caused by the finite ellipticity of Earth's

orbit. This amounts to only + or - 0.017 AU. The change in distance

has a real, but small, effect on the seasons. The Earth is nearest

the Sun in January, one of the coldest months in the northern

hemisphere. The seasonal changes therefore are milder in the northern

hemisphere and larger in the southern hemisphere than they would have

been if Earth's orbit were perfectly circular.

- Local Weather Extremes:

-

The change in insolation at the mid-latitudes (like

Charlottesville's) would not by itself cause the extremes of weather

we experience here (e.g. frigid winter temperatures). Instead, it is

mixing by wind currents of air masses from different

latitudes that produces the extremes. In the case of winter, the

north polar regions experience perpetual night starting in September

and lasting until March. The resultant drastic atmospheric cooling

creates the icy air masses that can produce very cold weather in the US

if they move over us.

- The Milankovitch Effect

-

The polar tilt and the properties of the Earth's orbit change

slightly with time over long periods (10's of thousands of years)

because of the gravitational effects of the other bodies in the solar

system. Small changes in the polar tilt, the size and shape of

Earth's orbit, or the timing of closest approach to the Sun can have

cumulative effects on heating of the atmosphere.

One of the important effects is

precession, discussed on the

Lunar Motions page, which changes

the timing of the solstices with respect to the Earth's distance

from the Sun.

There is good geophysical evidence for a correlation

between such astronomical changes and

major changes in climate over long time periods, particularly

in the form of ice

ages. This is known as the "Milankovitch Effect."

Astronomical and atmospheric effects on climate are discussed further

in Study Guide 19.

- The Milankovitch Effect

G. Effects of Intrinsic Lunar Motions

Reading for this lecture:

-

Bennett textbook: Ch. 2.1, 2.2

Study Guide 4

Lunar Motions and Their Consequences

Puzzlah preparation exercise. (Work alone or in a small group.)

- How wide is the Sun in degrees?

- [Optional] Repeat this exercise for the star cluster the Pleiades (in the constellation Taurus) viewed on a clear night. Which is larger, the Sun or the Pleiades?

- [Optional] If the whole sky (both hemispheres) covers 41,000 square degrees, how many times over could you fit the Sun's apparent disk into the whole sky?

- Measure the angular diameter of the Sun as follows. You

can do this on any day (clear or partly cloudy) when you can see the

disk of the Sun. Don't look directly at the sun. Instead put your

hand (palm out & fingers together) in front of your eyes at arm's

length. Close one eye. Then, carefully fold down fingers, keeping the

Sun's light covered until you can't remove any more fingers without

letting sunlight pass. Remember that your index finger will subtend

about 1 degree in width when held at arm's length.

-

Bennett textbook: CH 2.3 (lunar phases, eclipses), 3.1 (ancient astronomy)

Study Guide 5

Aztec Calendar Stone

Lunar Motions and Their Consequences

Optional reference on Mayan astronomy: Skywatchers of

Ancient Mexico by Anthony F. Aveni (Univ. of Texas Press,

1980/97).

Puzzlah Preparation Questions

Web links:

-

Spectacular star trail

photos by L. Harrison

Thanks to the capabilities of modern digital cameras for taking

hundreds of images in sequence, there are now scores of beautiful

time-lapse videos of the night sky, the Earth, and views from

the International Space Station made by both professional and amateur

astronomers. Links to some good video sites are given on

the ASTR 1210 Web Links Page.

Interactive

Earth & Moon viewer (includes software & add'l links)

JPL Tutorial on Earth motions and astronomical reference systems

Ice Ages (Wikipedia)

Lecture on the Milankovitch Effect (J. Frogel, OSU)

Milankovitch Cycles (Wikipedia)

Previous Guide

Previous Guide

|

Guide Index

Guide Index

|

Next Guide

Next Guide

|