ASTR 1210 (O'Connell) Study Guide

5. ANCIENT ASTRONOMY

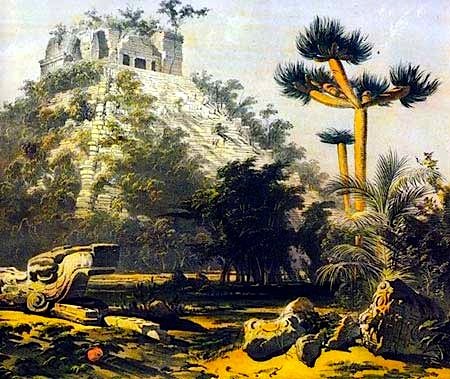

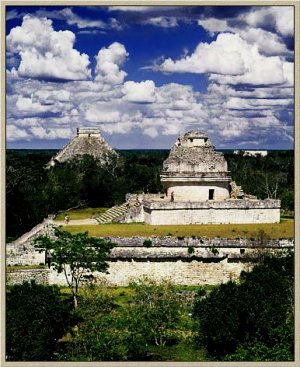

Maya pyramid El Castillo at Chichen

Itza

(Catherwood, ca. 1844)

|

"A single lifetime, even though entirely devoted to the sky, would not

be enough for the investigation of so vast a subject...And so

this knowledge will be unfolded only through long successive

ages. There will come a time when our descendants will be amazed

that we did not know things that are so plain to them...Many

discoveries are reserved for ages still to come, when memory of

us will have been effaced."

|

Introduction to the History of Astronomy

The quote above, by Roman philosopher Seneca the Younger, from ca. 50 AD, is characteristic of the views of the most far-sighted thinkers of ancient Greece and Rome. They knew that, for all of the important discoveries about the sky that had already been made (as described in Study Guide 6), they had barely scratched the surface of understanding the sky and its denizens. Seneca was right about the length of time it would take to achieve a more complete understanding of the cosmos. We've presented a quick overview of our modern understanding in earlier Study Guides, but most of that was accomplished only in the last century -- almost 2000 years after Seneca speculated about future discoveries. That's a measure of the difficulty in penetrating the complexity of the universe and of overcoming the limitations of our own inadequate human intuition and our pre-conceptions about what we might find. The "things that are so plain" to us today but would have been almost incomprehensible in earlier times extend well beyond astronomy to encompass all of modern science and technology. In the next few class meetings, we explore the historical record of progress toward understanding the sky, which began in pre-literate societies over 5000 years ago.Introduction to Ancient Astronomy

Evidence from ancient societies that left interpretable artifacts shows that many took astronomy very seriously, to the extent of including precise astronomical alignments in their buildings and ceremonial structures. In this lecture we discuss some of the ways early societies made and recorded observations of the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars. Then, we explore two of the most dramatic examples of ancient astronomy.-

Stonehenge, the striking arrangement of massive stone monoliths

in southern England from before 1500 BC, encodes astronomical

knowledge. But its builders left no written records, so we have no

idea how they acquired that or how they perceived the universe around

them.

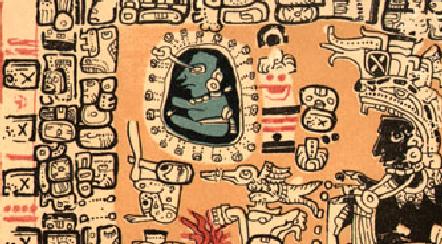

By contrast, the Mesoamerican cultures that flourished in Mexico and

Guatemala between about 500 BC and 1500 AD not only documented

extensive and painstaking observations of the sky, but they also left

records of a fascinating, pre-scientific cosmology built on those.

Their vibrant, if violent, view of the cosmos is beautifully captured

in the so-called

"Aztec Calendar Stone". The

Mesoamerican Maya culture is an amazing example of great

accomplishments in astronomy conjoined with ferocious societal

behavior.

A. Motions of the Planets on the Sky

What properties of the sky could be studied by ancient cultures without access to modern telescopes and other instruments? The most prominent, of course, are the changes in the positions of the Sun and Moon as described in Guide 4. Another conspicuous feature of the naked-eye sky in the planetarium simulations shown in class was the motion of the five bright planets. Although not as fast as the diurnal, solar, and lunar motions, the planetary motions are considerably more complex and placed greater demands on the abilities of ancient astronomers.-

[Recall that these

"motions" are measured by observers on Earth with respect to

the background patterns of the stars on the sky.]

- The speed of the motions depends on the planet, decreasing from rapid to slow in the order: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn.

- The general (average) motion of the planets against the star background is eastward in the sky.

- Mercury and Venus never move very far from the Sun (48 degrees in the case of Venus) and appear to move back and forth in front of or behind it.

- At least once per year, each of the planets halts its eastward motion and loops backward for a brief period before starting to move eastward again. This backward loop is called retrograde motion.

- The planets are confined to a relatively narrow band on the sky that is roughly centered on the ecliptic, the annual track of the Sun. The planets therefore are always to be found in the 12 Zodiacal constellations.

- The extreme north/south positions (i.e. distance from the

celestial equator) of the Sun, Moon, and planets differ from one

another.

- We now know that these differences are determined by the inclinations of the orbital planes of the planets and Moon to the ecliptic plane.

- The Sun moves along the ecliptic, so its maximal N/S positions are 23.5 degrees from the equator, as described in Guide 04.

- The Moon's orbit is inclined 5 degrees to the ecliptic, so its maximal

N/S positions are 28.5 degrees from the equator.

5 degrees may sound small, but it is 10 times the angular

diameter of the Moon, so it is easy to distinguish on the sky.

-

The phases of the Moon (i.e. the change in its apparent shape

in the sky) are caused by the fact that we view different fractions of

its Sun-illuminated half as it moves in its orbit during a month.

See Lunar Motions and Their

Consequences.

- The orbit of each planet has a different inclination with respect to the ecliptic. A planet's observed N/S extremes are affected both by its orbital inclination and its distance from the Earth.

B. Astronomical Measurements Without Instruments

The most elaborate astronomical instruments prior to the advent of telescopes were made out of metal and wood. However, even societies that lacked metalworking skills could make reasonably careful astronomical observations using other kinds of technologies, some of which we explain next:- Heliacal risings: Helios is the Greek

word for the Sun. Stars are said to exhibit "heliacal risings" if

they rise in the east just before the Sun. An illustration is

shown here. This is a

(rough) method of tracking the Sun's changing position with respect to

the stars. Recall that the Sun moves about 1 degree east every

day against the stars. Hence this is a date-keeping method.

For example, in ancient Egypt a heliacal rising of the brightest star,

Sirius, was used to forecast the Nile's annual flood. The method can

only be used for stars bright enough to be visible in the twilight

sky.

A modern example of a horizon intercept - Horizon intercepts: The alignment of a

rising/setting object with distinct features on the distant

horizon as seen from a special location is called a "horizon

intercept." An illustration is shown above. Horizon intercepts allow

one to track the date using the N/S position of the

setting/rising Sun against the horizon (more accurate than using

heliacal risings). It also allows tracking of the motions of the

Moon and planets and, in particular, the extremes of their

north/south motions. The horizon is a convenient reference plane for

tracking celestial objects; it is harder to provide alignment devices

that track objects when they are high in the sky.

-

Note: accurate Earth-sky angular measurements of this kind require

establishment of a reference direction. For instance, two

fixed points yielding a well-defined fixed line toward the horizon is

a reference against which to measure anglular positions of intercepts.

The two points could both be natural (e.g. a nearby rock and a

tree on the distant horizon) or they could both

be artificial --- the foreground road in the Moon image above,

for example. The most sophisticated of the artificial reference

systems were actually embedded into ancient buildings.

- Internal building alignments. Special designs, intended

to assist in making astronomical measurements or to reflect a

recurring important astronomical event (e.g. an equinox or solstice),

have been found built into many ancient buildings. Discovery and

analysis of such features is an important aspect of a new research

field:

"Archaeo-Astronomy" (see ASTR

3410).

Many ancient building alignments were intended to mark the rise or

set (i.e. the horizon intercepts) of important astronomical

objects. Some examples:

- The Sun at the equinoxes (east-west alignment). For

example, most ancient Greek temples have their long axes aligned

east-west, so that the rising or setting Sun illuminates the

interiors. The bases of the Egyptian pyramids are aligned almost

exactly east-west/north-south, in the case of the

Great

Pyramid of Khufu within 3 minutes of arc (1/20 of a degree).

-

The "El Castillo" pyramid, built by the Maya at Chichen Itza ca 950

AD, is not closely aligned E-W/N-S, but it features raised staircases

against which a rippled shadow is cast by the edges of the pyramid

at sunset near the equinoxes. See the image at the right. As the sun

sets, the shadow moves and is said to resemble the slithering of the

feathered

serpent deity Kukulkan, to whom the temple is dedicated.

- The Sun at a solstice (its extreme N/S positions). The rise/set points of the solstices do not lie east-west, because the Sun is 23.5 degrees from the celestial equator at these times. E.g. at Stonehenge, the line of sight from the center of the monument towards "The Avenue" and "Heelstone" points toward the rising Sun on the summer solstice. A number of structures, e.g. Newgrange in Ireland (ca. 3200 BC), are oriented toward sunrise at the winter solstice (shortest day the year).

- The Moon at its N/S extremes (28.5 degrees from the celestial equator): e.g. at Stonehenge, the line of sight over two pairs of special stones point toward Moon rise or set at the extremes. For details on the complex motions of the Moon, see Lunar Motions and Their Consequences.

- Bright stars. The rise/set points of stars are always the same during a given year, but they do change very slowly over time because of "precession" of the Earth's polar axis. Corrections for precession based on the date of a given ancient structure must be made before possible sight lines to stars can be explored. Examples of significant stellar alignments with megalithic structures include Nabta Playa in southern Egypt, from ca. 6000 BC.

- Planets at their N/S extremes: e.g. the Maya El Caracol observatory building contains alignments of windows and wall structures with special setting points of Venus on the western horizon.

- The Sun at the equinoxes (east-west alignment). For

example, most ancient Greek temples have their long axes aligned

east-west, so that the rising or setting Sun illuminates the

interiors. The bases of the Egyptian pyramids are aligned almost

exactly east-west/north-south, in the case of the

Great

Pyramid of Khufu within 3 minutes of arc (1/20 of a degree).

C. Astronomical Records

Recording of observations/interpretations is the key to scientific progress.

-

Although pre-literate societies were able to transmit some scientific

information via oral histories and recitation, they rarely progressed

far in understanding the world. They had a faulty record of their own

histories, let alone nature. Even crude methods of recording data

provide enormous advantages. Paradoxically, low-tech stone records

survive better than more elaborate paper records.

The first writing systems were developed ca. 3200 BC in the Near East

(Sumeria and Egypt) and were used mainly to record imperial and

dynastic histories or commercial transactions.

The earliest extant astronomical records (Chinese) are over 4500

years old. The best astronomical records prior to the European

Renaissance were developed by the Babylonians, Greeks, Chinese, and

Maya. At right is a Babylonian planetary almanac written in "cuneiform"

script (ca. 400 BC). The script was incised on a wet clay tablet which

was then fired to make a permanent record. The surviving Maya records

(both carved in stone and written in ink; see below) reveal

sophisticated observational capabilities.

It is difficult for people today, for some of whom time is measured

mainly in minutes elapsed between text messages, to picture the gulf

in time over which human civilizations developed. Written records of

any kind are sparse before about 500 BC. The earliest extensive,

coherent histories were written by the ancient Greek

historians Herodotus

and Thucydides

around 430 BC. For a little context, consider this: when Herodotus

visited and described

the Great Pyramid

of Khufu in Egypt ca. 450 BC, he was already as distant in time

from its construction as we are today from the reign of Julius

Caesar.

Stonehenge by moonlight

D. Stonehenge

Stonehenge, on the Salisbury plain in south-central England, is the

best known of thousands of "megalithic" ("giant stone")

monuments surviving from prehistoric times (roughly 3500-500 BC) in

northern Europe.

(Click

on the thumbnail at right for information on

megalithic sites in Great Britain and Ireland.) These consist mainly

of standing stones, dirt mounds and ditches, and evidence of former

wooden structures, now long decayed. Four examples are

shown here.

Very little is known about the peoples who built these. Unlike the

Maya or the Middle Eastern cultures, they did not incise their hard

stone surfaces with symbols or writing, and they left no other records

of any kind. Consequently, scholarly debate has raged over the

purpose of such structures. There is, however, good evidence that

their builders incorporated astronomical knowledge of the Sun, Moon,

and bright stars in some of them. That includes Stonehenge, which is

probably the best-studied ancient structure in terms of its

astronomical alignments and significance.

Stonehenge, on the Salisbury plain in south-central England, is the

best known of thousands of "megalithic" ("giant stone")

monuments surviving from prehistoric times (roughly 3500-500 BC) in

northern Europe.

(Click

on the thumbnail at right for information on

megalithic sites in Great Britain and Ireland.) These consist mainly

of standing stones, dirt mounds and ditches, and evidence of former

wooden structures, now long decayed. Four examples are

shown here.

Very little is known about the peoples who built these. Unlike the

Maya or the Middle Eastern cultures, they did not incise their hard

stone surfaces with symbols or writing, and they left no other records

of any kind. Consequently, scholarly debate has raged over the

purpose of such structures. There is, however, good evidence that

their builders incorporated astronomical knowledge of the Sun, Moon,

and bright stars in some of them. That includes Stonehenge, which is

probably the best-studied ancient structure in terms of its

astronomical alignments and significance.

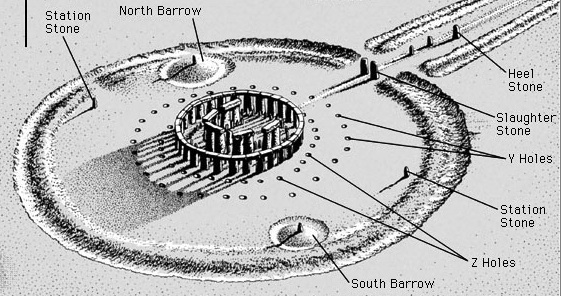

Construction at Stonehenge took place ca. 3100-1500 BC (over 1500 years!) in several major phases. This was a massive effort, involving, for instance, transport of specially-selected 5 ton stones up to 240 miles. The image above shows Stonehenge as it might have appeared in the period 2000-1550 BC.

-

To put Stonehenge in its historical context,

here is a timeline

showing other contemporaneous cultural developments. The construction

of Stonehenge started about 500 years before the Egyptians began

building pyramids, but the Stonehenge people never reached the

level of sophistication of the Egyptians.

Astronomical alignments: there are both

solar and lunar alignments built into Stonehenge.

Astronomical alignments: there are both

solar and lunar alignments built into Stonehenge.

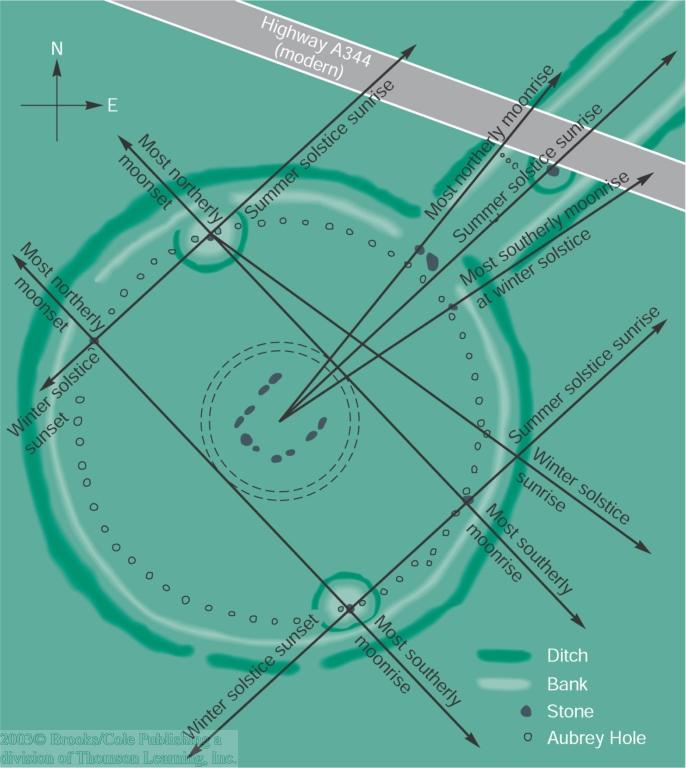

- Solsticial Alignments: A line from the

monument center to the "Heelstone" points toward the location

of sunrise at the summer solstice (the northernmost sunrise of

the year and the longest day of the year). The reverse points to

sunset at the winter solstice (southernmost sunset). The Heelstone is

a large, isolated stone lying outside the circular structures on the

centerline of the Avenue.

[Click on the

thumbnail at right for a chart of the alignments.]

-

Note that such "solsticial" orientations are not simply

east-west (which is much more common in ancient buildings).

The heelstone is north-east of the center of

Stonehenge.

A sketch of the Sun's path as it rises over the heelstone on the

summer solstice as seen from the center is shown below. The stone is

placed slightly south of the actual "horizon intercept," presumably

because one cannot mark that point with a large standing stone and

still see the Sun there.

- Lunar Alignments: The so-called

"Station Stones" are four stones lying just inside the circular bank

(labeled "SS" in the plan

drawing). Lines drawn through Station Stones 92 and 93 or 91 and

94

align with the N/S

maxima of the Moon's rise or set during the

18.6-year revolution

cycle in the "nodes" of its orbit.

-

The nodal cycle determines where on the sky the N/S maxima will

occur and also controls the pattern of lunar and solar eclipses.

(See Lunar Motions and Their

Consequences.)

Diodorus, a Greek historian during the 1st century BC, refers to

a "19 year" cycle traditionally associated with Stonehenge and

the Moon --- almost certainly the lunar nodal cycle.

Astronomers Gerald Hawkins, in his best-seller "Stonehenge

Decoded," and Fred Hoyle suggested in the 1960's that the circle

of 56 "Aubrey Holes" (dug at the inner periphery of the circular

mound) could have been used as an analog computer to track the motion

of the Moon, Sun, and the nodes of the lunar orbit in order to predict

eclipses. 56 years, or 3 nodal cycles, is required to bring solar

eclipses back to approximately the same locations on Earth's surface.

Though technically correct, this idea has found little support among

archaeologists.

Stonehenge is situated at a unique latitude: where the lunar and

solar sight lines just described

cross at right angles. It is possible that the Stonehenge

people chose this site for the monument because of this fact and

that this is the reason they invested so much effort (estimated

at 1.5 million person-days) in building it.

Before solar and lunar orientations could be built into

Stonehenge, its planners must have observed the sky for many

cycles---in the case of the Moon, many times 19 years. And they

needed a method to pass the information on from one generation to the

next (the lifespan then was only ~30 yrs). No stone, paper, or other

forms of records have been found.

The most obvious stone structures (the 5 pairs of massive trilithons

arranged in a horseshoe shape, see above right) were constructed last

but have no clear astronomical significance.

Stonehenge is the most elaborate structure in northern Europe

remaining from the period before 1500 BC. It clearly reflects the two

most important sky cycles (solar and lunar). But its central function

is still obscure. It may have served as an astronomical calendar

tracker, a memorial, a site for religious rituals --- or all of

these.

Stonehenge is situated at a unique latitude: where the lunar and

solar sight lines just described

cross at right angles. It is possible that the Stonehenge

people chose this site for the monument because of this fact and

that this is the reason they invested so much effort (estimated

at 1.5 million person-days) in building it.

Before solar and lunar orientations could be built into

Stonehenge, its planners must have observed the sky for many

cycles---in the case of the Moon, many times 19 years. And they

needed a method to pass the information on from one generation to the

next (the lifespan then was only ~30 yrs). No stone, paper, or other

forms of records have been found.

The most obvious stone structures (the 5 pairs of massive trilithons

arranged in a horseshoe shape, see above right) were constructed last

but have no clear astronomical significance.

Stonehenge is the most elaborate structure in northern Europe

remaining from the period before 1500 BC. It clearly reflects the two

most important sky cycles (solar and lunar). But its central function

is still obscure. It may have served as an astronomical calendar

tracker, a memorial, a site for religious rituals --- or all of

these.

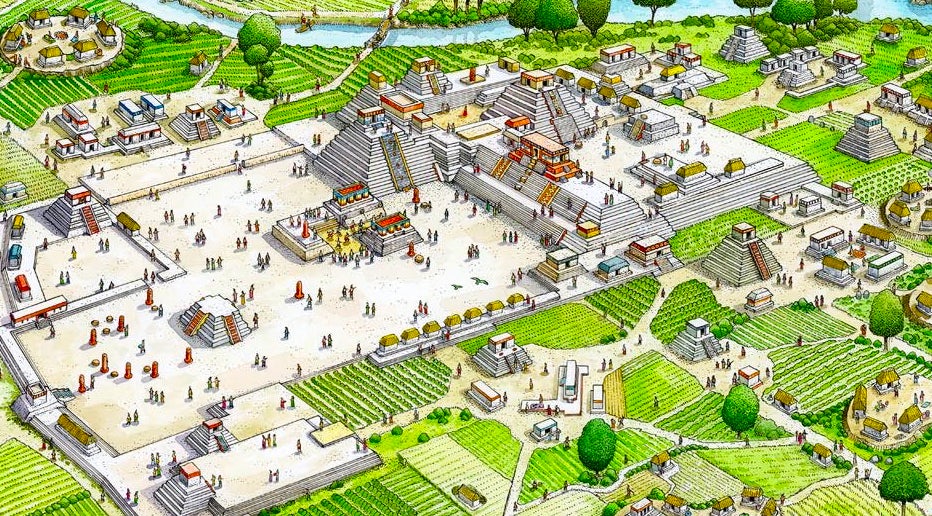

E. Maya Astronomy

People began migrating from Asia to the Western Hemisphere at least 20,000 years ago, and they relatively quickly occupied parts of both North and South America. Traces of scores of cultures from the period up to 2000 years ago have been discovered by archaeologists. The Maya were the most advanced ancient astronomers in the Western hemisphere. They represented the pinnacle of a 2000-year "Mesoamerican" cultural tradition, preceded by the Olmecs and Zapotecs and succeeded by the Toltecs and Aztecs. The Maya flourished 250-900 AD in the area now belonging to Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and Belize. They built many elaborate cities, including large pyramidal and other public & ceremonial buildings. Recent studies of Maya territory using airborne LIDAR technology has revealed extensive "suburbs" around the major cities as well as huge networks of connecting roadways and hundreds of small settlements -- all of which had been concealed by the jungle terrain. Much of this infrastructure is from the period 1000 BC - 250 AD, before the Maya "Classic" era. The scale of early Maya building had not been appreciated before the LIDAR surveys. Maya societies had a harsh, militaristic character, and city-states frequently waged war on one another. The civilization suddenly disintegrated beginning ca. 850 AD.- The reason for

the collapse

of the Maya civilization still isn't understood well. The

main symptom was that the people abandoned most of their cities and

spread out through the forests to live in small villages. They stayed

that way for hundreds of years.

A number of problems could have contributed: drought or other

environmental pressures, overpopulation, disease, invasion, or

political instability. Definitive causes have not yet been

identified. Probably a confluence of adverse natural and human

factors was at fault.

The Maya collapse was some 600 years before the arrival of the

Spanish explorers (ca. 1520 AD) and had nothing to do with military

conquest by Europeans.

-

Something similar happened ca. 1200

BC, at

the end

of the Bronze Age in the Eastern Mediterranean, when a dozen

different, formerly interdependent, cultures (including the Mycenaean,

Minoan, and Hittite empires) precipitously declined. The subsequent

400 years in Greece became known as the "Greek Dark Ages," when

literacy vanished.

"eyeing" the cosmos. Click for more images of the Codex.

Maya Observations, Sky Cycles and Calendars

|

Chichen Itza Today

Astronomical Tables in |

- Venus was believed to be a malevolent god, whose demands for blood sacrifice at critical times led to ritual murder by the Maya of both captives and their own citizens, including children. (The Toltecs and Aztecs, who became dominant after the Maya collapse, were even more enthusiastic participants in human sacrifice.) The Maya assiduously tracked Venus to forecast the god's intent toward themselves.

- But there is no evidence the Maya understood the origin of the celestial motions, which they attributed entirely to supernatural volition.

- From the standpoint of astronomy, there is an unpleasantly

sinister aspect to this. The astronomers, or "daykeepers," were so

good at making observations that it's inconceivable they hadn't

realized that the celestial cycles of the Moon and Venus

were strictly repeatable. And the more cycles they recorded,

the more confident they could be about it. In other words, they knew

that human intervention made no difference to the motions in the sky.

The astronomers must have colluded with the political and religious

leaders in pretending that the sacrificial rituals were effective.

-

There is a hint of this in the thriller movie Apocalypto, set

during the Maya classic period. At the start of the ostensibly

terrifying solar eclipse, two priests exchange a knowing glance. They

knew it was coming all along.

Uxmal, Maya city ca. 850 AD, with the Pyramid of the Magician at the left

The Long Count and the End of the World

-

The Maya believed in a recurring cosmic cycle of birth and

destruction during which the gods struggled to nurture a fruitful human

species. Three cycles, each ending in catastrophe for the world, were

thought to have preceded the then-current, fourth, cycle. The cycles

as interpreted by the (later) Aztecs are described

here.

Time within a cycle was tracked by the Long Count, in which

each day was assigned a unique number. Counts were expressed in a

modified base-20 system, the longest unit of which was

the baktun. A baktun is 20x18x20x20 = 144,000 days

or 394 solar years long.

Here is an example of

an inscription giving a date in the long count calendar.

Some Maya documents suggest that a

cosmic creation cycle would end in worldwide disaster after

exactly 13 baktuns, or 5125 years.

By cross-correlating Long Count dates with unique astronomical events

and historical dates after the Spanish conquest, archaeologists have

been able to convert Long Count dates to those in the Julian (Western)

calendar. The starting date of the fourth cycle (and the end

of the third) was determined to be 11 August 3114 BC. But that

implies that the end of the fourth cycle occurred on

21 December

2012!

You can find much speculation on the Internet before December 2012

about the meaning of the cycle turnover, including irresponsible

predictions of a looming

Doomsday. A handy "countdown to the apocalypse" calendar

is shown at the right. The predictions were nonsense, and there was,

obviously, no catastrophe at the predicted time. The doomsday

hucksters have since retreated into silence to count their money.

Remember that for all their skill in tracking the planets, the Maya

world view was riddled with superstition, and they showed no insight

regarding the true physical nature of the universe or even the size

and shape of the Earth. They had counting systems but had not

developed mathematical geometry, which would have helped them

understand the nature of sky cycles. Their writings were vague and

contradictory concerning the cosmic cycles, and some inscriptions

anticipate eras as much as 2020 years from now in an

inconceivably distant future. Finally, as is obvious from the

historical record, there was no worldwide cataclysm in 3114 BC, at the

end of the previous 13-baktun cycle. Same with 2012, and we have now

started the first baktun of a new cycle.

Some Maya documents suggest that a

cosmic creation cycle would end in worldwide disaster after

exactly 13 baktuns, or 5125 years.

By cross-correlating Long Count dates with unique astronomical events

and historical dates after the Spanish conquest, archaeologists have

been able to convert Long Count dates to those in the Julian (Western)

calendar. The starting date of the fourth cycle (and the end

of the third) was determined to be 11 August 3114 BC. But that

implies that the end of the fourth cycle occurred on

21 December

2012!

You can find much speculation on the Internet before December 2012

about the meaning of the cycle turnover, including irresponsible

predictions of a looming

Doomsday. A handy "countdown to the apocalypse" calendar

is shown at the right. The predictions were nonsense, and there was,

obviously, no catastrophe at the predicted time. The doomsday

hucksters have since retreated into silence to count their money.

Remember that for all their skill in tracking the planets, the Maya

world view was riddled with superstition, and they showed no insight

regarding the true physical nature of the universe or even the size

and shape of the Earth. They had counting systems but had not

developed mathematical geometry, which would have helped them

understand the nature of sky cycles. Their writings were vague and

contradictory concerning the cosmic cycles, and some inscriptions

anticipate eras as much as 2020 years from now in an

inconceivably distant future. Finally, as is obvious from the

historical record, there was no worldwide cataclysm in 3114 BC, at the

end of the previous 13-baktun cycle. Same with 2012, and we have now

started the first baktun of a new cycle.

Below are examples of a Maya observatory ("El

Caracol" at Chichen Itza, left) and the remarkable Aztec "Sunstone"

calendar, carved in 1479 (right). Click on thumbnails for more

images and an explanation of the Sunstone.

Below are examples of a Maya observatory ("El

Caracol" at Chichen Itza, left) and the remarkable Aztec "Sunstone"

calendar, carved in 1479 (right). Click on thumbnails for more

images and an explanation of the Sunstone.

|

|

Cultural Parallels, Cultural Clashes

Mesoamerican culture developed in isolation from the world outside the Americas, and there was no contact with Eurasian cultures before Columbus arrived in 1492 AD. Maya pyramids and glyph writing resembled their Egyptian counterparts, but they had been invented completely independently and in parallel and delayed by about 2500 years. However, the Maya easily exceeded the astronomical accomplishments of almost all the Eurasian civilizations at a comparable level of development. It is something of a shock to realize that for all their sophistication, the Maya and Aztecs, as well as all the other indigeneous groups of the Americas, were literally Stone Age people. They did not make extensive use of metals: for instance, they never developed even bronze weaponry, let alone steel. They did not use the wheel for travel, commerce, or the military. They did not have seagoing vessels. They did not have guns or gunpowder. They did not have horses or draft animals like oxen because those species were not present in the Western Hemisphere. When Hernan Cortes and his Spanish Conquistadors landed on the eastern shore of Mexico in 1519, he was facing a determined, warlike society -- but one of a kind that hadn't existed in Europe or Asia for over 4000 years. The result was rapid capitulation of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City) and the subjugation of the rest of the Mesoamerican empires over the next several decades. The same fate befell the even larger Inca Empire in western South America by 1572.Reading for this lecture:

-

Bennett textbook: 3.1 (ancient astronomy)

Study Guide 5

Lunar Motions and Their Consequences

The Aztec Calendar Stone

Optional references on Stonehenge: see Gerald Hawkins,

Stonehenge Decoded (1966) or John North, Stonehenge: A New

Interpretation of Prehistoric Man and the Cosmos (1996).

Optional reference on Maya astronomy:

Skywatchers of

Ancient Mexico by Anthony F. Aveni (Univ. of Texas Press,

1980/97).

Puzzlah Preparation Questions

-

Bennett textbook: Ch. 3.2

Study Guide 6

Optional references: Bertrand Russell, A History of Western

Philosophy; Arthur Koestler, The Sleepwalkers; Timothy

Ferris, Coming of Age in the Milky Way; J. L. E. Dreyer,

A History of Astronomy from Thales to Kepler.

Puzzlah prep:

- A (the lighter object) hits the ground first.

- B (the heavier object) hits the ground first.

- They hit at the same time.

-

You have two objects, A and B, both of which are the same shape.

B weighs twice as much as A. You drop both simultaneously

from a height of 3 feet. What happens?

Web links:

-

Slides shown in lecture (pptx)

Timeline (to

1650) of important events in the early history of science and

technology

Introduction to

Archaeoastronomy (UMd)

Astronomy of the Egyptian Great Pyramid

Stonehenge:

-

Introduction

to Stonehenge.Some of the illustrations above are taken from this

site.

Stonehenge Factsheet from the Royal Astronomical Society

Stonehenge (Wikipedia)

Murder at Stonehenge (segment in the "Secrets of the Dead" PBS series).

Animated 3-D Model of Stonehenge

Excavations at the Stonehenge complex (Jan 2007)

Virtual Tour of Stonehenge (English Heritage)

-

MesoWeb (good general site)

MesoAmerica Photos & Articles (Jacobs)

Photos of Maya Cities (McKenzie)

Photos of Maya Cities and comparisons to Catherwood's discovery paintings (Frogel) Introduction to Maya Astronomy

The Maya Calendar (Wikipedia)

The Maya Calendar (Meyer)

Brief notes on the Maya calendar (Chevalier, UVa ASTR 3410)

Astronomical Contents of the Dresden Codex (Boehm)

Breaking the Maya Code (Coe). Describes how misconceptions delayed interpretation of the Maya inscriptions for decades.

El Caracol, A Maya Observatory (O'Connell) Evidence that a massive drought caused the Maya collapse (2018)

A NOVA documentary updating our understanding of the Maya collapse (2022) The Aztec Calendar Stone (O'Connell) "The Great 2012 Doomsday Scare" (E. C. Krupp)

Debunking the "2012 Doomsday". A site injecting science and common sense into the

overheated Internet rhetoric about the "predicted" end of the world on 12/21/2012. Maya Culture on the big screen: Mel Gibson's Apocalypto

-

Trailer

Wikipedia entry (summary, sources, criticism)

"History Buffs" Episode (extracts, historical assessment)

Previous Guide

Previous Guide

|

Guide Index

Guide Index

|

Next Guide

Next Guide

|