ASTR 1230 (O'Connell) Supplementary Lecture Notes

7.1 MODERN OBSERVATIONAL ASTRONOMY

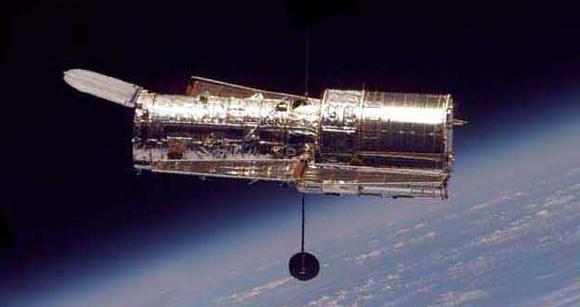

The Hubble Space Telescope in orbit.

A. INTRODUCTION

The human imagination has never been a match for the universe. That is why astronomy, more than any other science, has been regularly revolutionized by new observational discoveries. Since 1610, these have depended on telescopes. When telescope technology has developed slowly, as in the early 19th century, progress was slow. When technology surged, as in the late 20th century, progress was explosive. This lecture surveys the state of observational astronomy today, with some background on how we got here. In Lecture 2 we have already discussed the basics of telescope design. Here we discuss some of the milestone developments in telescopes. A key theme: to build an instrument at the frontier of performance is always costly in terms of brains and money. Thus, progress has coupled new technology and visionary astronomical pioneers with the generosity of wealthy private donors or the financial strength of governments.

B. AMERICAN OBSERVATORIES 1880-1950

Initially, telescopes were built adjacent to universities, usually in or near cities. However, the growth of artificial light pollution drove telescope construction to ever more remote sites, first in the southwestern US (e.g. California, Texas, Arizona), and ultimately to high mountains like Mauna Kea in Hawaii or the northern deserts of Chile. Optical and mechanical technology in the last few decades of the 19th

century had advanced to the point that the construction of large

telescopes was feasible. Most of these were associated with

universities. They were costly and required substantial private

donations. Important examples: (click on the links

for more information):

Optical and mechanical technology in the last few decades of the 19th

century had advanced to the point that the construction of large

telescopes was feasible. Most of these were associated with

universities. They were costly and required substantial private

donations. Important examples: (click on the links

for more information):

- Leander McCormick Observatory 26-in refractor (UVa, 1885). Largest in the US when dedicated. Click on the link for a history of astronomy at the University of Virginia. The optician Alvan Clark was responsible for figuring the lenses of the McCormick refractor and those of the other two large refractors listed next.

- Lick Observatory 36-in refractor (U Calif. 1888), the first mountaintop observatory. The advantages of placing telescopes at high altitudes in dry climates became obvious here.

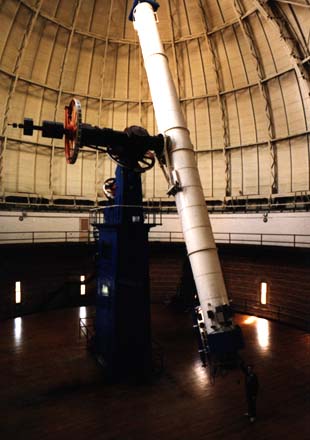

- The Yerkes Observatory 40-in refractor (Univ. of Chicago, 1897). The largest refractor ever built (see picture above right). It was not practical to build larger refractors (see Lecture 2 for details).

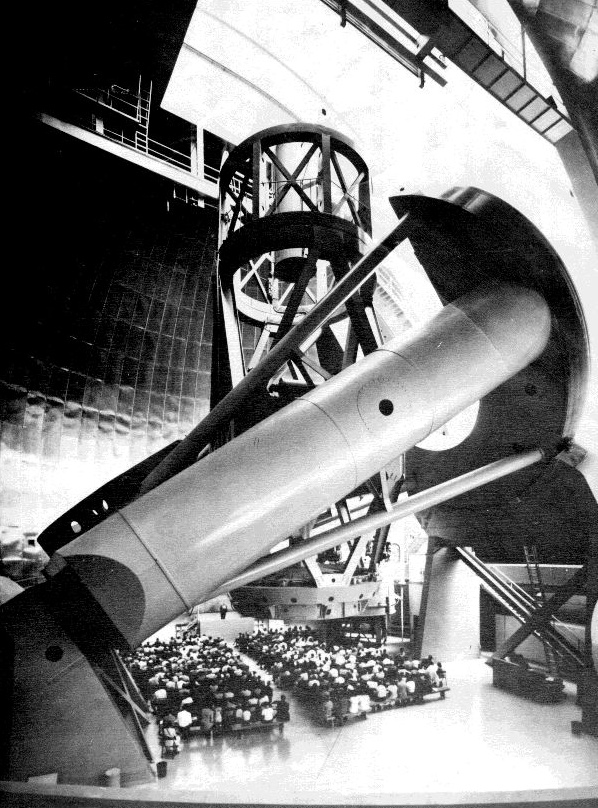

- The Mount Wilson Observatory 100-in reflector (1917), the most important telescope of the first half of the 20th century (see photo at beginning of this section). Hubble proved the existence of other galaxies and discovered the expanding universe with the 100-in.

- The Palomar Observatory 200-in (5-m) reflector (1948), the largest working telescope until 1992. The 20-year process of planning & building Palomar is described in a photo-history here. At right is a photo of the 200-in dedication in 1948. Here is a diagram of the telescope's unusual design. Work with the 200-in has concentrated on the structure & evolution of stars and galaxies, quasars (discovered with the 200-in in 1963), formation of galaxies out of intergalactic gas, measuring the expansion of the universe, and supermassive black holes in galaxy nuclei.

C. AMERICAN ASTRONOMY 1950-2000

TECHNOLOGIES

Until about 1975, despite many technical improvements, big telescope design was based largely on the concepts used for the Mt. Wilson 100-in telescope (designed ca. 1907). Unfortunately, the cost of extending such designs to sizes larger than 200-in was prohibitive. In the early 1980's a series of innovations was introduced that made yet larger telescopes affordable, mainly by reducing the total weight per unit optical collecting area. These included:

- Shorter focal length optics (requiring smaller domes)

- Lightweight structural materials

- Lightweight monolithic mirrors (thinner designs or honeycombed)

- Multiple-mirror designs, in which a large reflecting surface is

tiled with smaller (usually hexagonal) mirrors; this allows

construction of arbitrarily large telescopes

- Alt-azimuth mounts (less costly)

- High performance computer control for

active figure correction of thin mirrors and directional

control of alt-az mounts

- Thorough and rapid ventilation of domes to keep nighttime temperatures uniform and therefore reduce "seeing"

FUNDING/NATIONAL ORGANIZATION

Big telescopes are costly. Both public and private funding is now involved in building them. The experience of World War II, in which physical science and mathematics provided the key technologies leading to victory, convinced the government that broad-based federal support for basic science and technology was essential. This included astronomy, and since 1950 the federal government has become the largest source of support for research in astronomy. The two dominant sources of funds for astronomy are- The National Science Foundation

(NSF), which provides general research grants in astronomy

and directly supports the operations of, among others:

- The National Optical Astronomy Observatories. In the 1970's, NOAO developed a 160-in (4-m) telescope design based on the 200-in, and this has been reproduced, more or less closely, in multiple versions around the world. At right is the 4-m dome at Kitt Peak National Observatory.

- The National Radio Astronomy Observatory, which operates radio telescopes at a number of sites in the US and the ALMA millimeter-wave array in Chile. The headquarters of NRAO is in Charlottesville.

- The Gemini Observatories, two 8-m class telescopes operated by an international consortium.

- The Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, which features a unique 3-mirror design in which the primary and tertiary mirrors have been figured on a single piece of spin-cast glass 8.4-meters in diameter and achieves a wide field of view. The telescope is intended to repeatedly image the entire usable sky every three nights, searching for transient or moving targets while building up an ultra-deep combined image of the sky. LSST is now under construction in Chile.

- The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which designs and deploys a wide variety of satellite observatories and deep space probes. Because of their cost (see below), NASA contributes over 10 times as much funding per year to astronomy as does NSF.

D. EM SPECTRUM COVERAGE

Astronomers today have access to almost the entire cosmic electromagnetic spectrum described in Lecture 2 and ranging from radio waves at the long wavelength end to gamma rays at the short wavelength end. All of the devices for detecting EM waves are called "telescopes," even though some (e.g. radio antennas) look nothing like classical optical telescopes. The first steps outside the confines of the optical band were taken in the 1930's and 40's when natural radio waves were first detected from cosmic objects. Radio astronomy developed rapidly in the 1950's, followed by infrared, ultraviolet, X-ray, and gamma ray astronomy. Because of absorption by the Earth's atmosphere, observations of most cosmic EM radiation other than optical and radio require a telescope in space (see below). You can find compilations of information on telescopes at the following websites:E. COMPETITION FOR TELESCOPE TIME

Access to powerful telescopes is provided through a competitive proposal review process, in which an astronomer, or group of astronomers, submits a detailed proposal which is reviewed in competition with other proposals by a "time allocation committee." There are many more proposals than can be accommodated. There is always intense competition for "dark of the Moon" time (only two weeks out of each month), which is required for work on very faint objects at ground-based sites. One out of two proposals will be successful on "under-subscribed" telescopes, while only one out of 5-10 will succeed for more cutting-edge facilities like HST or the Chandra X-ray Observatory. It typically takes astronomers 2-4 weeks to write a competitive proposal. This is why they seem busy most of the time.- Telescope time allocation committees are one example

of peer review, which is the basic method by which

standards are preserved in all sciences. Scientists seeking access to

privileges or special resources (telescopes, supercomputers,

acclerators, space missions, laboratory space, grant money,

publication space, etc.) must regularly submit their ideas to the

scrutiny of experts. Typically, scientists spend 1-2 weeks each year

reviewing and reporting on the work of other scientists.

F. THE LARGE BINOCULAR TELESCOPE

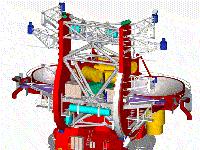

The Large Binocular Telescope is a good example of current telescope building technology. UVa is a member of the consortium of universities operating the LBT in southern Arizona.

- The LBT consists of two 8.4-m diameter mirrors on a single mount (corresponding to the light collecting area of 3,500 8-in telescopes).

- It can operate as two separate telescopes (pointing at the same object), or it can combine the beams of the two mirrors to act as an interferometer yielding the effective optical resolution (see Lecture 2) of a 23-m diameter telescope.

-

Click

here for pictures of the LBT being assembled. The official

dedication was held in October 2004.

Click

here for pictures of the LBT being assembled. The official

dedication was held in October 2004.

G. SPACE ASTRONOMY

1. Why telescopes in space?- Freedom from atmospheric absorption (see Lecture 2) permits observations in the UV, X-Ray, Gamma Ray, Infrared, and Sub-millimeter regions that are blocked for ground-based observatories.

- Freedom from the bright atmospheric night sky. The sky on the ground is 3-10x brighter in the visible, 60-1000x brighter in the near-IR.

- Freedom from atmospheric turbulence (seeing), allows improved resolution

- Must be self-contained: power, pointing, computer control,

heating/cooling, communications with Earth

- Must be highly reliable (failure probability---for any reason---only 2-5% per year during early deployment); no repair possible (except HST); must survive launch; must survive harsh environment (e.g. radiation, vacuum, 300o temp differential side-to-side).

- Complexity: high tech equipment; complicated operations.

- Expensive transportation (at right)

- ====> Labor intensive!

- Hubble Space

Telescope

- First proposed by Lyman Spitzer in 1946 but not launched until 1990. Long lifetime (to 2020 or beyond). Orbits at 300 mi altitude (see picture at top of page).

- Small (94-in) mirror, but very high precision. Can be serviced by Space Shuttle crews (only such scientific satellite). Carries up to 6 powerful instruments (imagers, spectrographs). Highest resolution optical-band images ever (0.04 arcsec). Deepest images (4 billion times fainter than naked eye limit) of universe in UV, optical, near-IR.

- The final servicing mission for HST was completed in May 2009, with the delivery of two new instruments, the repair of two others, and installation of a number of housekeeping upgrades. You can find full coverage of the servicing mission at this NASA site.

- Chandra X-Ray Observatory

- Long-lifetime satellite observatory for observing cosmic X-ray sources. X-Rays have EM wavelengths of a few Angstroms, about 2000 times smaller than visible light.

- Uses grazing incidence optics with very high precision, nested mirrors (46-in diameter). Gives resolution of about 1 arc-sec (highest ever for X-rays).

- X-rays are only emitted by very high-temperature gas (10

to 100 million degrees), so Chandra probes the "high energy" universe.

Chandra X-Ray image of hot interstellar gas and accreting neutron stars

in the galaxy NGC 4697. (C. Sarazin, UVa)

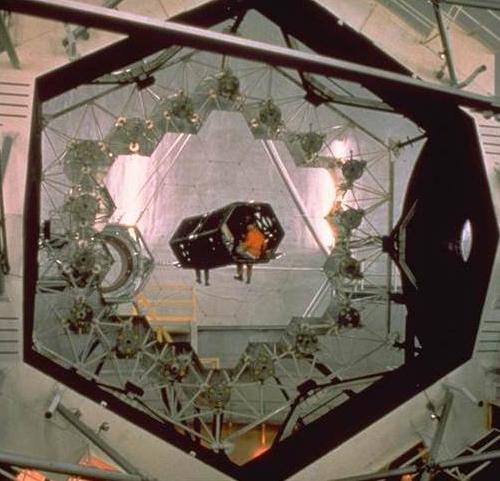

- ASTRO missions

- First proposed 1978 for multiple short-duration missions on Space Shuttle. First launched in 1990.

- UV observatory with 3 telescopes, 2 missions 1990, 1995, up to 15 days in orbit. (Picture at beginning of this section).

-

Click here for pictures of UIT and the Astro missions.

Click here for pictures of UIT and the Astro missions.

Web links: links are embedded in the text above.

Back to Lecture 7

Back to Lecture 7

|

Lecture Index

Lecture Index

|

Last modified December 2020 by rwo