ASTR 1230 (O'Connell) Lecture Notes

SUPPLEMENT: MOTIONS IN THE SKY

& COORDINATE SYSTEMS

Star trails around the South Celestial Pole

in a 6-hour exposure (by Lincoln

Harrison).

A. MOTIONS OF BRIGHT OBJECTS

Cyclical motions of bright objects in sky were the main historical stimulus for the study of astronomy. We first describe these motions as they might have been seen by ancient astronomers but then explain them from a modern perspective. The table below lists celestial motions which are easily detectable by someone on the Earth without telescopes. We call these "apparent" motions, because they can be produced by motions of the observer as well as by the objects themselves.| OBJECT | PERIOD | MOTION* |

|---|---|---|

| ALL | Daily ("diurnal") | Rotation Westward* |

| SUN | Annual (365 d) | (i) 1 degree/day Eastward* |

| (ii) North/South* | ||

| MOON** | Monthly (29 d) | (i) Eastward, N/S* |

| (ii) Phase change | ||

| PLANETS (5)** | Months-Years | Generally Eastward, but with Westward loops* |

-

*Except for the diurnal motion, motions are measured with respect to the stars.

The diurnal motion is measured with respect to the local horizon.

**The Moon and the planets move on paths near to, but not identical with, the annual path of the Sun seen against the stars (the "ecliptic").

-

If you're patient for about 20 minutes, you can easily detect the

diurnal wheeling rotation of the whole night sky by comparing

the position of the stars to a fixed foreground object (e.g. a tree).

If you have a digital camera capable of taking exposures longer than a

few minutes, you can readily take images showing star trails,

like the one at the top of the page.

Celestial motions may be complicated, but they are repeatable

over periods of months to years, and their cyclic nature was quickly

recognized by many cultures. It was this feature that encouraged

people to search for a deeper understanding of them.

The cycles also naturally became the basis of practical calendar

systems. For instance, Western calendars are based on 7-day weeks

(one day for each of the bright moving lights in the sky: the Sun,

Moon, and five planets) and 30-day months (one lunar cycle).

Thought experiment

Imagine that we couldn't easily see the cyclic sky phenomena---that,

for instance, the Earth were perpetually shrouded in fog-like clouds.

In these circumstances, it would have been difficult or impossible to

recognize the regularity in the sky cycles, and astronomy might well

never have developed. That would have inhibited the development of

fields such as physics as well and perhaps all of science. What kind

of world might we live in today if that one piece of the scientific

enterprise had been missing? In a somewhat different context, the

famous science fiction

story "Nightfall" by Isaac Asimov describes the terrible fate of a

society whose planet experiences night only once in a few thousand

years.

Imagine that we couldn't easily see the cyclic sky phenomena---that,

for instance, the Earth were perpetually shrouded in fog-like clouds.

In these circumstances, it would have been difficult or impossible to

recognize the regularity in the sky cycles, and astronomy might well

never have developed. That would have inhibited the development of

fields such as physics as well and perhaps all of science. What kind

of world might we live in today if that one piece of the scientific

enterprise had been missing? In a somewhat different context, the

famous science fiction

story "Nightfall" by Isaac Asimov describes the terrible fate of a

society whose planet experiences night only once in a few thousand

years.

B. EXPLANATION OF MOTIONS

In the rest of this lecture, we explain the diurnal motion and the Sun's motion from a modern scientific perspective.-

It took many centuries for astronomers to arrive at the correct

interpretation described here. Ancient Greek astronomers understood

most of this after several hundred years of work, but the knowledge

was lost and only rediscovered during the Renaissance, 1300 years

later.

The key to complete understanding of celestial motions was introduced

by the Greeks: mathematics.

-

The Greeks built mathematical models of the sky based on the

concepts in plane and spherical geometry which they

had developed. These reduce a bewildering array of complex phenomena

to a much simpler set of mathematical concepts.

- Intrinsic motions of the objects themselves with respect to one another

- The motion of the observer, or the platform on which he/she is standing---in this case, the Earth.

tilted, spinning, moving platform.

C. EFFECTS OF EARTH SHAPE AND SPIN

- Earth is a sphere.

- We experience night on the shadow side of the Earth (away from the Sun). Half of Earth is always in shadow.

- The bright blue daylight sky is sunlight scattered by molecules in the Earth's atmosphere. The daylight glare overwhelms the light of the planets and stars, so we cannot see them when the Sun is above the horizon.

- Earth spins on its axis with respect to the stars once in 23

hours, 56 minutes (one "sidereal day"). This causes the

apparent "diurnal" rotation of sky.

- The universe is not spinning around the Earth once per

day.

- The Earth's spin is counterclockwise (eastward) as seen from above the Earth's north pole. This means that the apparent rotation of the sky as seen from the Earth's surface is westward

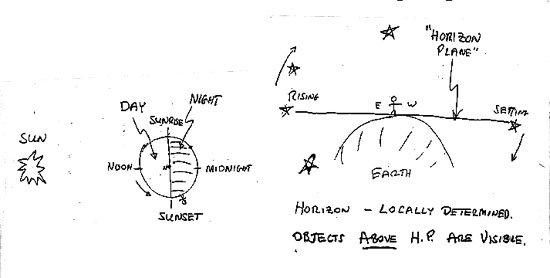

- The left-hand panel of the diagram above shows Earth viewed from above its North Pole. The Earth rotates counterclockwise in this diagram, carrying observers with it.

- The positions where observers on the equator are experiencing sunrise, noon, sunset, and midnight are marked. Mean local times of day corresponding to these points are 6 AM, 12 noon, 6 PM, and 12 midnight, respectively.

- The right hand panel shows the local "horizon plane," which is the plane "tangent" to Earth at your location. You can see objects above the plane but not below---at least in principle (neglecting blocking by local features such as buildings, trees, mountains, etc.).

- Note that half of the entire celestial sphere is always above your horizon plane.

- However, the horizon plane (and visible hemisphere) is different at each location on Earth.

- The horizon plane sweeps across the sky as Earth spins. Astronomical objects appear to move in the opposite direction (shown by the arrows in the figure). Objects rise over the eastern half of the horizon plane and set toward the western half.

- By combining the concept of the horizon plane with the definition of local time in the left-hand panel, you can visualize what parts of the sky are observable at any given time of night.

D. EFFECTS OF EARTH'S MOTION IN ORBIT

- Earth is a planet moving in orbit around the Sun

- Its orbit is nearly circular (distance to Sun varies only 3%)

- Its orbit lies in a plane called the ecliptic plane. Seen face-on, the orbit is technically an ellipse but deviates only slightly from a circle. Seen edge-on, the orbit is a thin line.

- Earth orbits the Sun in 365.25 days (one year) moving at

~66,000 mph. Its motion is counterclockwise as seen from above

Earth's north pole.

- The stars visible at night are those "opposite" the Sun,

and these change continuously during the year because of Earth's

orbital motion. See the figures above. In May, the constellation

Scorpio will be prominent in the night sky, while in November, it lies

in the direction of the Sun and therefore is not visible because of

the atmospheric glare.

- Warning! these drawings, and most others you

will see in this course and in astronomy texts, are grossly distorted

and not to scale! In reality, the Earth's orbit is 100 times the

diameter of the Sun; the Earth is 100 times smaller than the Sun; the

stars are vastly distant from the Earth's orbit; and the stars in a

given constellation are not necessarily near one another in space.

Obviously, no one could produce or sensibly view a figure like this

drawn to actual scale.

- Also, we are viewing Earth's orbit here such that our line of sight makes an angle of about 25o to the ecliptic plane. From this perspective, Earth's orbit looks highly elliptical, whereas it is nearly circular seen face-on. Without explanations, drawings like this one help encourage the erroneous notion that the seasons are caused by large changes in the Earth-Sun distance.

- Warning! these drawings, and most others you

will see in this course and in astronomy texts, are grossly distorted

and not to scale! In reality, the Earth's orbit is 100 times the

diameter of the Sun; the Earth is 100 times smaller than the Sun; the

stars are vastly distant from the Earth's orbit; and the stars in a

given constellation are not necessarily near one another in space.

Obviously, no one could produce or sensibly view a figure like this

drawn to actual scale.

- The Earth's motion around the Sun is counterclockwise in the

drawings above. This produces an apparent eastward "motion"

of the Sun as seen from the Earth against the stellar reference

frame.

- In the drawings, the Sun in November would be seen in projection against Libra (if you magically remove the glow of the daylight atmosphere), while in December, 30 days later, the Earth has moved such that the Sun is seen in projection against Scorpio (which is about 30 degrees east of Libra).

- Therefore, the average "reflex motion" of the Sun seen from Earth against the reference frame of the stars is 1 degree per day eastward and 30 degrees per month.

- "Solar" vs. "sidereal" days:

-

The "solar day" is the time between noon on successive days.

The daily motion of the Earth in its orbit means that the Earth must

spin a little more than once on its axis to bring the Sun back

to the point of local noon. The extra amount is 4 minutes, on

average. This accounts for the difference between the sidereal

rotation period of the Earth (23 hours, 56 min) and the average solar

day (24 hours). [An illustration of the effect of Earth's motion

during one sidereal day is shown here.]

- The Sun's location on the sky as seen from Earth is confined to

the ecliptic path, which is the projection of the

ecliptic plane on the celestial sphere.

- The "Zodiac" is the set of constellations through which the ecliptic path passes. (See Lecture 1.) Those are the only constellations which have been illustrated in the drawings above. Of course, there are 76 other constellations not shown. You should know the names of the Zodiacal constellations and how to locate them on your Sky Wheels.

E. EFFECTS OF THE TILT OF EARTH'S AXIS

North/South Motions of Solar System Objects

- The polar rotation axis of the Earth is not perpendicular to

its orbital plane. It is tilted by 23.5 degrees. See the figure

below (again, exaggerated for clarity):

- The rotation axis is fixed in direction with respect to the stars, not with respect to the Sun. This means that as Earth orbits the Sun, the axis continues to point in the same direction in 3D space. See the illustration linked here.

- Because of this axis tilt, the Sun, as viewed from the Earth, will appear to move north and south of the celestial equator through the year by a maximum of + or - 23.5 degrees. In the drawing above, if the North Pole is at the top, the Sun will be seen at its most southerly position.

- Equivalently, as seen from Earth, the path of the Sun on the sky (the ecliptic path) is inclined 23.5 degrees to the celestial equator.

- Since the Earth's Moon and the planets also lie near the ecliptic, they will also follow paths inclined to the equator.

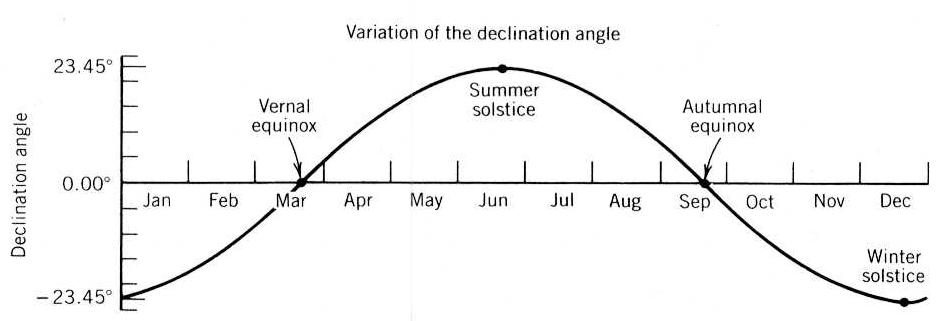

- The following diagram shows

the ecliptic and the equator drawn on the celestial sphere (see below for the definition of the celestial sphere).

- The Sun's N/S distance from the equator as a function of date is

shown in the diagram below (click for enlagement).

- The total amplitude of the Sun's swing in N/S distance during the year is 2 x 23.5 = 47 degrees.

- The ecliptic crosses the celestial equator at two points called equinoxes.

- When the Sun is at an equinox, night and day are "equal," each being 12 hours long at all latitudes. The "vernal equinox" occurs around March 21, while the "autumnal equinox" occurs around September 21.

- The Sun is at its greatest distance from the equator (23.5 degrees) at the solstices ("sun stationary"), which occur around June 21 and Dec 21. At these times, one hemisphere experiences its longest day, the other its shortest.

The Seasons

- The Sun's distance north or south from the Celestial Equator determines the hours of daylight and the angle at which sunlight strikes Earth's surface at a given latitude. It thus determines "insolation," or the amount of sunlight incident on a unit area of the Earth's surface during 24 hours.

- The cumulative effect of this differential heating is responsible for

the seasons. The "official" beginning dates of

spring, summer, autumn, and winter correspond to the Vernal Equinox,

Summer Solstice, Autumnal Equinox, and Winter Solstice,

respectively.

- The change in the geographic shadow distribution caused by

the tilt is quite dramatic (even though the shadow always covers

exactly one hemisphere of the Earth). Here are two images of the way

the shadow is distributed at about 2 PM Eastern time on August 1

(left) and December 1 (right). The Earth's surface moves eastward through

the shadow. You can immediately tell from the image which latitudes are

receiving more sunlight in a 24 hour period. Click on the thumbnails

for an expanded view.

August 1 December 1 - Therefore, seasons are caused by the tilt of the Earth's rotation axis, not the distance to the Sun. If the seasons were a distance effect, winter, for instance, would occur simultaneously in both the southern and northern hemispheres; but instead, the seasons differ by 6 months in the two hemispheres. The Earth is actually nearest the Sun in January, one of the coldest months in the northern hemisphere.

- The change in the geographic shadow distribution caused by

the tilt is quite dramatic (even though the shadow always covers

exactly one hemisphere of the Earth). Here are two images of the way

the shadow is distributed at about 2 PM Eastern time on August 1

(left) and December 1 (right). The Earth's surface moves eastward through

the shadow. You can immediately tell from the image which latitudes are

receiving more sunlight in a 24 hour period. Click on the thumbnails

for an expanded view.

F. ASTRONOMICAL COORDINATE SYSTEMS

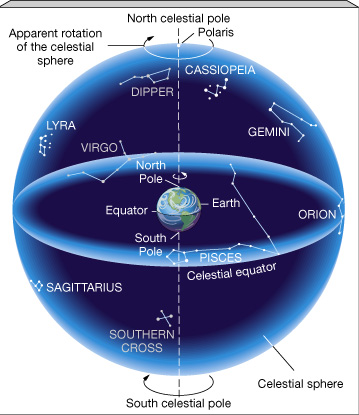

Astronomers locate objects in the sky by using a set of coordinate systems. Each coordinate system is tied to a particular reference frame---for instance, the local reference frame of a given observer at a given latitude on Earth's surface at a given time of night. But we already know from the discussion above that the local reference frames for different observers are different and that their orientation in space is constantly changing as Earth rotates. So, some more universal reference frame is needed to tie all these local frames together. The universal frame used for astronomical observations from Earth is based on the concept of the celestial sphere, as illustrated below.

-

The celestial sphere is a geometric construct on which to display the

angular positions of astronomical objects. It is an imaginary hollow

sphere centered on Earth. The main reference points on the

sphere are the

projections of the Earth's poles and equator onto the

sphere. The primary astronomical coordinates for an object are based

on the location which that object would appear to have on the sphere

if viewed by an hypothetical observer at the center of the Earth. The

sphere is imagined to spin around the Earth once a day, carrying all

celestial objects with it.

- At what times of night is a target above the horizon?

- At a given time, approximately where is a target (e.g. which quadrant: SE, SW, NE, NW)?

- What is the maximum altitude a given target can have from the horizon?

G. RIGHT ASCENSION AND DECLINATION

- The primary coordinate system on the celestial sphere is

conceptually identical to the terrestrial two-angle coordinate system

for finding places on the Earth's surface.

-

The terrestrial angular coordinates are

latitude, for measuring north-south distances, and

longitude, for measuring east-west distances.

- The celestial Equatorial Coordinate System likewise uses two

angles to measure positions on the celestial sphere.

-

Declination is analogous to latitude, while Right

Ascension is analogous to longitude.

- The two figures above show the celestial sphere as viewed from

outside. As we see in the left-hand figure, Declination

(abbreviated DEC or Greek "delta")

is measured (in degrees) north or south of the celestial equator and increases

northward. The North and South celestial poles have DECs of

+90 and -90 degrees, respectively. The equator has DEC = 0.

- Another visualization of the RA and DEC system is shown here.

- Right Ascension (RA or Greek "alpha") is measured as shown in the right-hand figure above. Lines of constant RA are great circles (also called "hour circles") drawn through the celestial poles. The zero point of RA is the vernal equinox (the point where the Sun crosses the celestial equator moving north), and RA increases eastward. (The zero point is arbitrary, just like the zero point of the longitude system was arbitrarily chosen to be Greenwich, England.)

- Rather than measuring in degrees, RA is measured in time

units of hours, minutes, and seconds up to one sidereal

day. Therefore, RA values run from 0 hours to

23h59m59s.

-

On the equator, one hour of RA corresponds to 15 degrees

of arc. But because of the convergence of the lines of

constant RA toward the pole (see figure above), at other declinations

one hour of RA corresponds to fewer than 15 degrees of arc.

From its definition, the RA of a given object is the time interval

between the passage of the vernal equinox through your local meridian

and the subsequent passage of the object through the

meridian.

- Beware confusion between "minutes" and "seconds" of time and those of arc!

-

The RA and DEC coordinates of the stars change only very slowly

with time and can be considered fixed for the purposes of this

course throughout the year.

- The slow changes are the result of two effects: the change

(or "precession") in the direction of the Earth's

polar axis and small motions (called "proper motions")

of the stars with respect to one another. Precession is discussed in

Supplement 4.1.

- The RA and DEC of the Sun and Moon (and other solar system objects) change continuously as they move from day to day. The Sun is always on the ecliptic, so its DEC is always between -23.5o and +23.5o. At the vernal equinox (near March 21), the RA of the Sun is 0 hours and at the autumnal equinox (near Sept. 21), it is 12 hours; at the equinoxes, the DEC of the Sun is 0o.

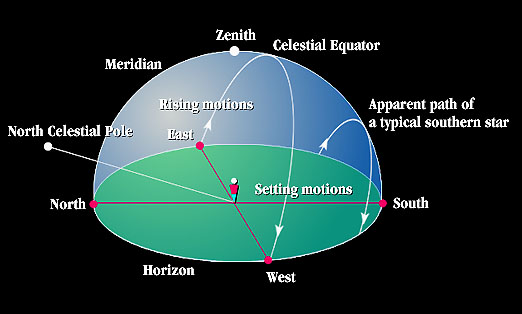

Earth's Surface. (Green shows the horizon plane.)

H. THE LOCAL REFERENCE FRAME

The local reference frame of any Earth-bound observer is determined by that person's instantaneous horizon plane. The diagram above shows the local reference frame and its main reference points.-

The zenith is the point on the sky directly overhead.

The meridian is the great circle drawn on the

celestial sphere through the pole(s) and the zenith. The meridian

divides the local night sky hemisphere into an eastern and a western

half. The points where the meridian crosses the edge of the horizon

define the directions on the horizon plane to due North and

South.

The points where a great circle running through

the zenith at right angles to the meridian cross the horizon plane define

the directions to due East and West.

Visibility of Astronomical Objects: Declination

It is important to know how to determine when astronomical objects are well placed for observation from your particular location on Earth at a given date and time. The "DEC-HA" method is the quickest way to do this:- The figure below shows how the Declination of an astronomical

object controls its visibility with respect to your horizon. The

shaded plane is the horizon. Star tracks are shown on the celestial

sphere. The orientation of the sphere for your location is the

same at all times of the year (though the Sun moves to

different locations along it and thus changes the part of it which is

visible at night).

- As the Earth rotates on its axis during the course of a night, the stars appear to rise in the east, move along the heavy lines of constant declination, and set in the west. A star is farthest from the horizon when it crosses your meridian. At this time it is said to transit.

- The figure helps you visualize how long in each 24 hour period stars at different DECs are above your horizon. Stars at some DECs (like +60 degrees here) are always above your horizon, 24 hours a day. Such stars are called circumpolar stars; they never set. Most of the stars in the left-hand part of the startrail image at the top of this webpage are circumpolar stars.

- By contrast, stars at -30 degrees DEC are above the horizon only for short periods. There are some stars farther south which are never above your horizon. You would have to change your latitude to see them.

Visibility of Astronomical Objects: Hour Angle

- Knowing DEC alone is not sufficient. The celestial sphere rotates continuously about the axis through its poles. An object's DEC may always be the same, but its east-west position in your local coordinate system changes during the night.

- To locate an

astronomical object in the sky, you therefore need to know one additional

quantity besides DEC: the distance of its hour circle from your local

meridian.

- The Hour Angle or HA is defined to be

the angle measured along the equator between the hour circle of a

star and your meridian. See the diagram above. HA is quoted

in time units (hours, minutes, and seconds).

-

Objects to the west of the meridian have

positive HA, while objects to the east have

negative HA.

By convention, HA's are always in the range -12 hours to +12

hours.

A star with HA = 2 crossed the meridian (i.e.

reached transit) two hours ago, while a star with HA = -1 will be on the

meridian (will transit) in one hour.

- You must know both HA and DEC to determine visibility.

- An object on the celestial equator (with DEC = 0) with HA = -6 hours (+6 hours) is just rising (setting) on the horizon. It will be above the horizon for 12 hours out of each 24. It will rise due east and set due west.

- From Charlottesville, objects south of the equator will be above the horizon for fewer than 12 hours. They will rise south of due east and set south of due west. They will cross the horizon at HA's smaller than 6 hours east or west.

- Objects north of the equator will be above the horizon for more than 12 hours. They will rise north of due east and set north of due west. They can be above the horizon even if their HA's are larger than 6 hours east or west.

- Any object in the circumpolar region is above the horizon all the time (for any HA), but cannot be seen in the daytime because of scattered light from the Sun.

Sidereal Time

- To determine the Hour Angle of a target we must know the current position of the zero point of RA, the vernal equinox. This is given by the sidereal time or ST. ST is defined to be the hour angle of the vernal equinox, and it is the fundamental measure of astronomical time of day. Sidereal time runs from 0 to 23h59m59s.

- By this definition, ST is also equal to the RA

of an object now on the meridian.

- The ST at midnight is always the RA of the Sun plus 12 hours.

- At a given ST, the HA of a star with a given RA is:

- HA = ST - RA

- Examples, if the sidereal time is now 8 hours:

- An object with an RA of 8 hours has HA = 8 - 8 = 0

and is now crossing the meridian (transiting).

- An object with an RA of 10 hours has HA = 8 - 10 = -2 hours.

It is two hours east of the meridian and will transit in two hours.

- An object with an RA of 5 hours has HA = 8 - 5 = +3 hours. It crossed the meridian 3 hours ago and is now west of the meridian.

- An object with an RA of 8 hours has HA = 8 - 8 = 0

and is now crossing the meridian (transiting).

- If the numerical value of HA (apart from the sign) in this

expression is larger than 12, then add or subtract 24 hours to put

it in the range (-12 to +12). Examples:

- If ST is 1 hour but RA is 23 hours, then the formula gives

-22 hours. In this case, add 24 hours to obtain HA = +2 hours.

The star is 2 hours west of the meridian.

- If ST is 23 hours but RA is 2 hours, then the formula gives + 21 hours. In this case, subtract 24 hours to obtain HA = -3 hours. The star is 3 hours east of the meridian.

- If ST is 1 hour but RA is 23 hours, then the formula gives

-22 hours. In this case, add 24 hours to obtain HA = +2 hours.

The star is 2 hours west of the meridian.

- Sidereal time runs faster than the mean solar time that

our watches use by 3 minutes and 56 seconds per day, which is the

result of the Earth's orbital motion around the sun. This means that

the sidereal time at a given standard time changes continuously by

2 hours per month (or 24 hours in a year).

- If the ST at 9 PM

EST tonight is 6 hours, one month from now it will be 8 hours.

- It is useful to memorize the ST-local time conversion for a couple

of dates.

- On March 21 (the vernal equinox), at 9 PM EST the ST is also 9 hours. ST at midnight is 12 hours.

- On September 21 (the autumnal equinox), at 9 PM EST the ST is 21 hours. ST at midnight is 0 hours.

- A table listing the ST at 9 PM EST throughout the year is given in Appendix B of the ASTR 1230 Manual. (Remember that this is given for standard time, not "daylight time.")

- A handy sidereal time calculator can be found here. Just enter the longitude of Charlottesville (78 degrees 30 minutes west), and the calculator will show you the current ST. You can then estimate the ST for any later time tonight (but remember that the ST will change by 3 minutes 56 seconds after a lapse of 24 mean solar hours).

- Using the HA/DEC system and an equatorially-mounted telescope, you can quickly locate objects in the sky if your know their RA, DEC, and the ST. One practical problem: HA changes continuously, so when you predict HA, you need to allow time to set the telescope!

- You can use your Sky Wheels to roughly locate objects in the sky. RA and DEC coordinate ticks are marked along the equator and along lines of constant RA at 3 hour intervals. You can use these to determine approximately the maximum altitude of objects with given coordinates or the quadrants in which they will appear at a given time of night. You can also get an approximate value for the ST on any date and time by reading off the RA of an object on the meridian at a given time.

- Modern computerized telescopes, such as those used in this course, do the conversions for you once they have been calibrated, so you can deal exclusively in RA and DEC units for objects.

Altitude & Meridian Slice

- The HA/DEC system is part of the celestial Equatorial Coordinate System defined with respect to the poles and equator. However, it is often useful also to know how to locate an object with respect to your horizon plane.

- Altitude is defined to be the angle between a star

and your horizon plane. In general, you need to use trigonometry to

find the altitude of an object with a given HA and DEC.

- However, when a star transits (i.e. crosses your

meridian), there is a simple relation between its DEC, your

latitude, and its altitude. This is illustrated in the figure above,

which shows a geometric "slice" through your local meridian.

- Based on the diagram, the altitude of a transiting star above the southern

horizon (SALT in the diagram above) is given by the following

expression, where LAT is your latitude.

-

SALT = DEC + (90o - LAT)

- LAT = 38o at Charlottesville, so here SALT = DEC + 52o.

- The celestial equator (DEC = 0) has SALT = 52o at Charlottesville. .

- Objects with DEC = LAT have altitudes of 90o, i.e. they cross through the zenith.

- Based on the diagram, the altitude of a transiting star above the southern

horizon (SALT in the diagram above) is given by the following

expression, where LAT is your latitude.

- SALT is a useful concept for determining how high in the sky a

planet or the Moon, for instance, can be on a given night.

- As an example: the Moon orbits in a plane which is tilted

5o from the plane of the ecliptic. Since the maximum

DEC of the Sun (or the ecliptic) is +23.5o, the maximum

DEC of the Moon is +28.5o. The maximum altitude

of the Moon above the southern horizon is then:

-

SALT = 28.5o + (90o - 38o) =

80.5o.

- As an example: the Moon orbits in a plane which is tilted

5o from the plane of the ecliptic. Since the maximum

DEC of the Sun (or the ecliptic) is +23.5o, the maximum

DEC of the Moon is +28.5o. The maximum altitude

of the Moon above the southern horizon is then:

Related Web links

-

Interactive

Earth & Moon Viewer (includes software & add'l links)

Astronomy

Without a Telescope (introduction to naked-eye astronomy by Nick

Strobel)

Positional

Astronomy (technical details on coordinate systems, motions, etc

by Fiona Vincent)

Back to Lecture 3

Back to Lecture 3

|

Lecture Index

Lecture Index

|

Next Lecture

Next Lecture

|

Last modified December 2020 by rwo

Star trail image copyright © Lincoln Harrison. Zodiac and axis tilt drawings copyright © by Nick Strobel. Equinox, RA, & Dec, drawings copyright © 1974,5 by Edmund Scientific Corp. Text copyright © 1998-2020 Robert W. O'Connell. All rights reserved. These notes are intended for the private, noncommercial use of students enrolled in Astronomy 1230 at the University of Virginia.