ASTR 1230 (O'Connell) Lecture Notes

3. OBSERVING TECHNIQUES

Lara Croft, the Tomb Raider, at her telescope

A. PREDICTING GOOD WEATHER

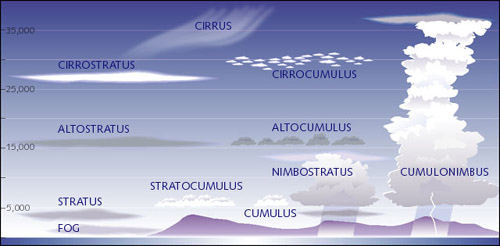

Astronomers need good weather. Ideal conditions are cloudless, windless, low humidity, and stable. Even high altitude, thin "cirrus" clouds (see picture below) that TV weather forecasters would ignore can seriously hamper many kinds of astronomical observations. On the other hand, less critical observations can be made through gaps in lower level clouds as they pass over.

- www.cleardarksky.com:

Gives predictions of local

observing conditions for next 48 hours, based on forecast maps from

the Canadian Meteorological Center. An example chart is shown below.

In the first four rows, dark blue coding indicates the best

conditions. You can click on any bin to see the large-scale map on

which the forecast is based. The site also includes links to Sun/Moon

rise/set information, star maps, and other items.

- 7 Day US Weather Service Forecast for Charlottesville

- Infrared-visible satellite maps of cloud cover (Weather Underground)

- NCAR Real Time Weather Data

B. JUDGING SKY CONDITIONS

Even when weather is reasonably good, it is important to learn how to evaluate prevailing conditions at the telescope. The main determinants are the following:- Residual Sunlight: The sun illuminates the sky for a considerable period after sunset. The end of astronomical twilight is defined to be the first time after sunset (or last time before sunrise) when there is no trace of sunlight measurable in the sky. (This is a more restrictive definition than "civil twilight.") The sun must be at least 18 degrees below the horizon for full darkness. You can find tables of the times of sun rise, set, and twilight on the Web (e.g. timeanddate.com). Here is an annual table of evening/morning twilight for Charlottesville (times are EST; add one hour for EDT).

- Transparency: means an absence of

clouds, haze, or fog that would absorb or scatter starlight. Although

low-altitude clouds are the most obvious, high-altitude cirrus clouds

are more commonly a problem. Transparency predictions for

Charlottesville are included on

the cleardarksky.com

displays.

-

A quantitative measure of transparency is given by the

magnitude of the faintest star you can see with the naked eye.

The bowl of the "Little Dipper" provides a convenient set of standard

stars, with approximate magnitudes of 2,3,4,5. See this image.

More elaborate techniques for estimating limiting magnitude are given

at obs.nineplanets.org.

More information on the magnitude scale is given on

the Stellar Astronomy page.

- Seeing: "Seeing" is defined to be the diameter of star images (measured in seconds of arc) caused by turbulence in the atmosphere. See the discussion in Lecture 2. "Twinkling" of stars is a sign of an unstable atmosphere, which will probably produce bad seeing. But you can only actually determine the seeing through a telescope. One technique you will use in Lab 3 is to measure the diameter of the components of a binary star of known separation.

- Other Atmospheric Effects: See these pages for additional background on effects of the atmosphere:

- Moonlight: If the moon is in the sky and more than "half-full" (astronomers would say "between first quarter and last quarter"), moonlight scattered by the atmosphere can easily obscure fainter telescopic targets (like nebulae and galaxies). Astronomers divide each month into "bright time" and "dark time" according to the phase of the moon (bright time is the period between first and last quarter phase). Of course, only near its full phase is the moon in the sky all night long, so parts of "bright time" nights can still be dark. Judge effects by the faintest stars you can see.

- Light Pollution: a growing problem

everywhere and certainly here in Charlottesville. Terrible when the

Stadium lights are on. Impact will vary with the amount of low-level

dust or mist in the atmosphere. Again, judge effects by the faintest

stars you can see.

-

Here are nighttime

satellite images of the USA showing the extent of light

pollution.

Also

see The

World Atlas of Artifical Night Sky Brightness.

For more information on light pollution and how to control it,

see the International

Dark Sky Association website.

C. OBSERVING LISTS AND FINDING CHARTS

Before you come to the observatory, you need to know what objects you intend to observe and how to find them. In some cases, the target list for a lab is specified in advance; in others, you are free to choose from many possibilities. Primary lists of potential targets, with brief descriptions and sometimes observing hints, can be found in the ASTR 1230 Lab Manual (see semesterly and all-sky lists in Lab 4) and the Mag 5 Star Atlas. It is probably best to choose targets first by astrophysical category (e.g. star cluster, nebula, galaxy) and then rank candidates in order of location in the sky and brightness.-

Familiarity with the constellations and use of your Sky Wheels will

help locate the brighter targets (e.g. stars) that have names associated

with constellations. However, for many targets (e.g. Messier objects),

you will need to use their coordinates to locate them.

These are discussed in the next section.

Brightnesses are measured

in magnitudes. Stars

up to magnitude 11-12 are visible in the 8-in telescopes. However,

more diffuse objects can be considerably more difficult to see than

stars of the same magnitude.

- Heavens Above: very useful reference giving current positions for solar system objects (including comets & asteroids), star charts, bright star lists for each constellation, predictions of Earth satellite passages (including Iridium flares and the International Space Station), and other info. This link provides listings specific to Charlottesville.

- US Naval Observatory: detailed information on solar system objects and bright stars for any date

- The Messier Catalog of Deep-Sky Objects (SEDS) The Messier Catalog (compiled by Charles Messier in 1781) is the primary list of (110) brighter northern hemisphere non-stellar objects: star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies. This site has finding charts for the Messier and brighter NGC objects in each constellation.

- The Caldwell Catalog of Deep-Sky Objects (Wikipedia): updated list of brighter non-stellar objects, including the southern hemisphere.

For fainter targets, you may want to make finding charts, which

show their immediate vicinity, as an aid to locating them. Here are

some sites providing sky or finding charts:

For fainter targets, you may want to make finding charts, which

show their immediate vicinity, as an aid to locating them. Here are

some sites providing sky or finding charts:

- Heavens Above

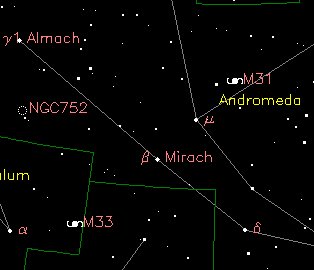

- Your Sky: an "interactive planetarium" which can produce standard wide-angle bright star charts or "virtual telescope" charts near given targets to a range of magnitude. A YourSky chart for the region near the Andromeda and Triangulum galaxies (M31 and M33) is shown at the right.

- Skyview: the "Internet's Virtual Telescope," which can produce images of any part of the sky to high resolution from a large database. Includes the optical-band Digital Sky Survey and data in other bands from radio to gamma ray. Skyview is a research tool as well as a key resource for planning observations.

- Google Sky and WikiSky provide sky viewers based on a multiplicity of image sources. These are still in development.

D. TARGET COORDINATES AND SKY LOCATION

For best viewing, objects should be as high in the sky (as far from the horizon) as possible during the time you will be observing. Sky location is determined by an object's astronomical coordinates, the time of night, and the date. Unless there is no alternative, you should avoid observing any object at an altitude of less than 30 degrees above the horizon. The most important questions you need to answer in planning observations are:- At what times of night is a target above the horizon?

- At a given time, approximately where is a target (e.g. which

quadrant: SE, SW, NE, NW)?

- What is the maximum altitude a given target can have from the horizon?

- Astronomical objects are located in the sky by their Right Ascension and Declination (RA and DEC), which correspond to longitude and latitude, respectively, on the celestial sphere. DEC is measured in angular degrees, just as is latitude on Earth. But RA is measured in units of time; see the Supplement for details.

- Your zenith will always fall at a DEC equal to your terrestrial

latitude. That is 38 degrees for Charlottesville. Stars with DECs

smaller than 38 degrees will always cross your meridian south of the zenith,

while stars with larger DECs will always cross north of the zenith.

- The celestial sphere rotates around the Earth in 23 hours 56 minutes, not 24 hours. This means that a given point on the sphere returns to the same location in your local sky 4 minutes earlier each night. You must take this systematic shift in the sphere's orientation into account in locating targets.

- The sidereal time (ST) describes the location of the "zero-point" of the RA system on the celestial sphere and hence the current east-west orientation of the celestial sphere. ST is numerically equal to the amount of time that has elapsed since the point where RA = 0 (which is the vernal equinox) last crossed your local meridian. ST at a given solar time (clock time) is equal to the RA of an object that lies on your local meridian at that time. The sidereal time at a given clock time increases by about 4 minutes in 24 hours. That amounts to a 2 hour increase in the ST at a given clock time every month. A handy sidereal time calculator can be found here. Just enter the longitude of Charlottesville (78 degrees 30 minutes west), and the calculator will show you the current ST. You can then estimate the ST for any later time over the next few hours (but remember that the ST will change with respect to local time by an additional 4 minutes after a lapse of 24 EST hours).

- By knowing the ST and the RA for any object, you can determine how far east or west it is from your local meridian (in units of time). That is, how long it has been since it crossed your meridian (if it is now west) or how long it will be until it crosses (if it is now east). This time is called the hour angle (HA) of an object. It is, of course, continuously changing.

- By knowing both the HA and the DEC of an object, you can

locate it precisely in the sky. This requires dealing with the

special geometry of the celestial sphere.

-

For a given target, HA = ST - RA. A positive HA means the

target is west of the meridian; a negative HA means it is east of

the meridian.

In using HA to estimate the location of an object in the sky, you must

take account of the fact that because of the convergence of lines of

constant RA toward the poles, a given E-W distance in time converts to

different distances in angle depending on the DEC of the object.

In using DEC you must take account of the fact that the celestial

sphere is tilted with respect to your local horizon (unless you

are observing from the N or S pole).

-

That implies that stars with certain declinations (below -52 degrees)

will never be visible from Charlottesville.

Other stars, however, (above +52 degrees) will

always be above your horizon; these are called

circumpolar, and they never set.

You can quickly determine which stars are circumpolar by rotating

your Sky Wheels through 24 hours. Circumpolar stars never go below

the horizon edges.

- The altitude of an object is its angular distance from the nearest point on the horizon. By knowing the DEC of a target and your latitude (38 degrees) for Charlottesville, you can easily determine the maximum altitude of any target. This occurs when it crosses your local meridian or "transits". For Charlottesville, the altitude of a transiting object from the southern horizon is equal to DEC + 52 degrees. This implies, for instance, that the celestial equator crosses the meridian at an altitude of 52 degrees.

- You can use your Sky Wheels to roughly locate objects with given coordinates in the sky. RA and DEC coordinate ticks are marked along the equator and along lines of constant RA at 3 hour intervals. You can use these to determine approximately the maximum altitude of objects with given coordinates or the quadrants in which they will appear at a given time of night. You can also get an approximate value for the ST on any date and clock time by reading off the RA of an object on the meridian at a given time.

E. LAB REPORTS & OBSERVING FORMS

- Appendices D and E in the ASTR 1230 Lab Manual describe how you are expected to use the standard observing forms to record observations with binoculars or telescopes and how to write up your lab reports. Read these sections carefully.

- It is strongly recommended that you fill out the "prep" part of each form before going to the Observatory.

- To keep forms neat, fill out all sections in pencil and erase as necessary.

- Blank observing forms and a sample, filled-out form can be found here.

Assignment

- Download, print, and read the notes for Lecture 3.

- Take the Review Quiz for Week 4 on the Collab site.

- Read Appendices A and B in the ASTR 1230 Manual

- Review the material in the "motions and coordinates" supplement to this lecture (link given below).

- Start Lab 3 at the earliest opportunity.

Related Web links

-

See links to useful sites included in the text above.

Lecture Supplement on Astronomical

Motions and Coordinates

Astronomy

Without a Telescope (introduction to naked-eye astronomy by Nick

Strobel)

Observational Astronomy for Amateur Astronomers (David Haworth)

Interactive Earth & Moon Viewer (includes software & add'l links) Norton's Star Atlas and Reference Handbook (Amazon) (a standard reference for all serious amateur astronomers) The World At Night (nice collection of nighttime images and videos)

Previous Lecture

Previous Lecture

|

Lecture Index

Lecture Index

|

Next Lecture

Next Lecture

|

Last modified December 2020 by rwo

Text copyright © 1998-2020 Robert W. O'Connell. All rights reserved. Noctilucent cloud image copyright © P-M. Heden. These notes are intended for the private, noncommercial use of students enrolled in Astronomy 1230 at the University of Virginia.