ASTR 1210 (O'Connell) Study Guide 13

Apollo 17 landing site in Taurus-Littrow Valley

A. General

- Size: Diameter 3500 km = 1/4 Earth; largest satellite relative to

its primary; 5th largest overall.

- "Moons" and "planets" are not intrinsically different kinds of

bodies; a "moon" simply orbits a planet, rather than the Sun.

"Planet" Mercury, at 4900 km in diameter, is smaller than two

"moons."

- Orbit and rotation: The Moon's orbit is elliptical with a

semi-major axis of 384000 km (238000 miles) but a relatively large

eccentricity of 0.05, which means that its distance from the Earth

varies by 42000 km (26000 miles) during any given orbit. Its orbital

period is 27.3 days. Its orbital properties are continually changing

slowly by virtue of the influence of gravitational interactions with

the Sun and with the non-spherical shape of the Earth (see

below).

-

The rotation, or "spin," period of the Moon is 27.3 days --- the same

as its orbital period. This is called synchronous

rotation. Since the Moon completes one rotation in one

orbital period, this implies that the

same face of the Moon is

always pointed toward Earth, and we call that face the "near side."

The "far side" of the Moon can never be seen from Earth and was only

photographed for the first time in 1959, when a USSR spacecraft was

sent into orbit around it.

- Telescopic exploration began in 1609 (by Galileo). Telescopes revealed a complex topography, including mountains, craters, "maria," and numerous smaller-scale structures --- all easily visible because the Moon has no perceptible atmosphere.

- Atmosphere: ~none. Lunar gravity is too small to retain atmospheric gases, so these escape to space, except for a tiny residual.

- Surface reflectivity: Despite its appearance in our night sky, the Moon's surface is actually very dark. A good comparison of the relative brightness of the Earth and Moon is shown in the picture at the upper right, taken from a spacecraft on its way to Jupiter. The Moon has a low albedo (reflectivity) of only ~7% because it is is covered by a regolith, a layer of powdery fragments from impacts, a few meters deep.

- For a large selection of maps and other data on the Moon's surface, see the USGS Moon Information Page.

B. Main Terrain Types

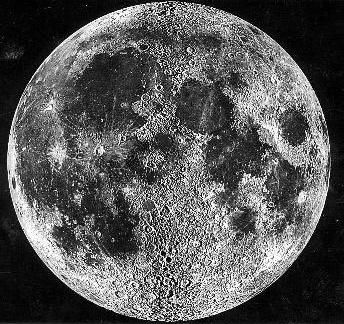

The two main lunar terrain types are highlighted in the image of the full Moon at right. Click for more images and information.- Highlands: rough, light colored, heavily cratered

- Maria: dark, round, smoother (variations < 150 meters).

Here is a

recent full-surface video of the Moon, compiled from

Lunar Reconnaisance Orbiter imaging, which nicely illustrates the

contrast in surface types.

Here is a

recent full-surface video of the Moon, compiled from

Lunar Reconnaisance Orbiter imaging, which nicely illustrates the

contrast in surface types.

C. Impact Topography

The Moon's surface testifies to the fact that the surface topography of most rocky planets is shaped largely by brutal impacts of asteroids, planetesimals, and comets. Although they should have realized this earlier, astronomers have only widely accepted the importance of impacts for the last 60 years. On the Moon, and most other solar system bodies with hard surfaces, the impact history is preserved in the form of extensive cratering. But impacts are responsible for most of the other major lunar surface features as well, including the mountains and maria.-

Click here for a

comparison of the appearance of six planetary surfaces.

Here's

a quiz

(by Emily Lakdawalla) for more experienced planetary surface

aficionados that asks you to identify high-resolution (1 km) images of

18 different solar system bodies. The tremendous variation in appearance

is mainly due to the differences in surface composition.

- The impact rate was higher at early times (4 Byr ago), when the

solar system was filled with many planetesimals not yet accreted by

planets (see discussion below).

- But even if the impact rate were constant in time, the longer a surface has been exposed to impacts, the more cratering it will have accumulated.

- Therefore:

- Older surfaces have higher crater densities (number per square mile).

- Younger surfaces have lower crater densities

- Crater counts vs. size can be calibrated to provide age estimates.

- A large regional difference in crater densities on a given object

is evidence of re-surfacing activity. We see such differences

between the highlands and maria on the Moon. The highlands have many

more craters per unit area than the maria. Hence, we infer that the

maria are significantly younger than the highlands and

represent regions that experienced more recent re-surfacing by molten

material.

-

Such differences are present in even more dramatic

form in cases such

as Enceladus, the sixth

largest satellite of Saturn, which has an icy, rather than rocky,

crust. Enceladus is shown in the image above right. Click for an

enlargement and note the large differences in cratering density caused

by younger ice flows covering over ancient cratered terrain.

- Earth has little surface impact cratering because plate tectonics recycles its surface material and atmospheric weathering erodes all structures.

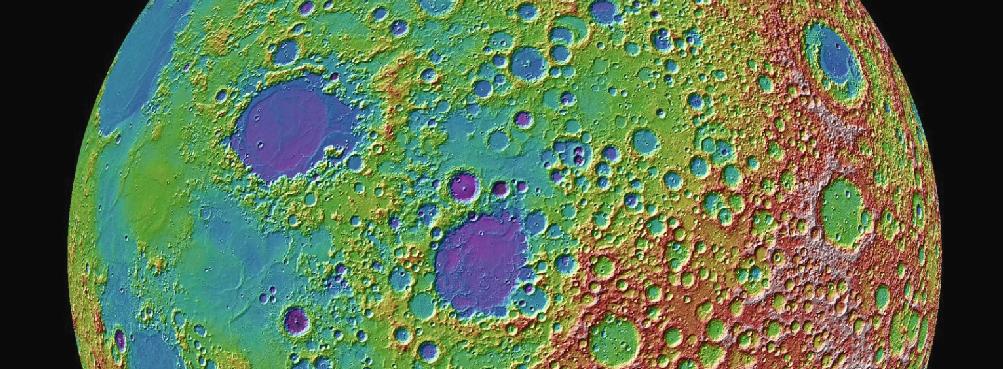

Topographic Map of East Limb of Moon (Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimiter)

The "near-side" is at the left; the "far-side" on the right. Click for

the full image.

D. Topographic Features

Click for illustrations

Click for illustrations

- Preserved: no weathering by rain, wind

- Craters: On Earth, we find craters mostly on volcanic terrain. On the Moon, craters are everywhere. Lunar craters were produced by impacts, not volcanic activity. Scales range from millimeters to over 180 miles diameter. The circular shapes, raised rims, and ejecta blankets are typical of impact events. In the highlands, the cratering density is so high that all craters overlap others.

- Maria: Large, roughly round basins; produced by major impacts after the lunar surface had solidified, and subsequently filled by dense, dark lava welling up from the interior. Maria exhibit relatively few craters.

- Mountains: Altitudes to 25,000 feet. All are related to impacts, not to plate tectonics (as on Earth). Extended ranges tend to lie at borders of maria basins and were formed during huge mare impacts.

- Rilles: canyons produced by lava flows, not water

E. The Apollo Missions

NASA's Apollo program was the US response to the USSR's breakthrough achievements in launching the first artificial satellite ("Sputnik," October 4, 1957) and the first human into space (Yuri Gagarin, 1961). In May 1961, President Kennedy committed the US to send Americans to the surface of the Moon within 9 years.

-

Despite enormous challenges, this daunting goal was actually

accomplished by NASA by 1969, the USSR having dropped out of the

Moon race in the late 1960's. The US

committed tremendous resources

toward achieving success.

The Apollo program involved a methodical series of ever

more sophisticated missions, based on

successively more capable

rockets leading to the

Saturn V, the most powerful

built to that time. The Saturn V had a payload capacity twice

that of the current-day

Falcon Heavy.

The SpaceX

Starship, now under development, will be the first to match or

exceed the Saturn V in lifting power.

Astronaut training, including

extra-vehicular excursions, took place

in carefully planned phases of one-, two-, and three-person low Earth

orbit missions before attempts at reaching the Moon were made.

Robotic spacecraft (e.g. the Surveyor missions) paved the way by mapping the surface

of the Moon and locating potential landing sites.

Apollo 8,

carrying the first humans to reach escape velocity from Earth and to

circumnavigate the Moon (without landing), was launched in December of

1968 (shown above right). NASA took a

major

risk with the timing of this mission because humans had never

before flown on a Saturn V rocket or employed other key elements of

the Apollo 8 technology, such as lunar orbit insertion. The crew took

the first iconic photograph of the space age,

showing Earth rise over the limb

of the Moon.

Apollo 11

achieved the first human landing on the Moon on July 20, 1969,

at

a

site in the mare named the "Sea of Tranquility." Over the next 3

years, 5 additional Apollo flights explored a variety of lunar terrain

(see

this map

and this

mosaic of close-up

images). Astronauts carried out a number of experiments and

collected

samples of lunar soil and rocks for return to Earth. In later missions

they used "rover" vehicles to travel up to 4.7 miles from the landing site.

Apollo 15 landing site and rover

F. Geology of the Moon

The Apollo program returned rock samples and a wealth of other information about the geology of the Moon.- The overall density of the Moon is 3.3 gr/cc, which is lower than the mean value for the Earth (implying fewer heavy metals) but comparable to its outer layers.

- The Moon's surface contains more refractory (hard to melt) materials than Earth and fewer volatiles

- No sedimentary rocks; only trace amounts of water in rocks

at the Apollo sites

- In the last 20 years, observations from a number of spacecraft have suggested the presence of water on the Moon, e.g. ice lying in constantly shadowed craters (T ~ 40K) near the poles. Deposited by comets? Possibly useful for human colonies. But results on recoverable reservoirs of water are inconclusive so far.

- Highlands: Lower density rocks, anorthosites (Ca, Al rich);

igneous (deposited molten).

-

Very old ~ 4.5 Byr.

The oldest Earth rocks are younger, but Earth's surface is

tectonically recycled and such old rocks are rare.

- Maria: higher density rocks "basalts" (more Fe, Mg rich); igneous; younger ~ 3.8 Byr

G. Interior

- The Apollo astronauts left seismic detectors behind on the Moon's surface, and these transmitted data back to Earth for several years. Unlike Earth, the Moon is seismically very tranquil --- implying the complete absence of large scale tectonic motions (which were not expected anyway on the basis of the Moon's topography). However, small amplitude Moonquakes do occur because of tidal stresses, and these allow its internal structure to be probed (though not in the detail possible for Earth).

- The lunar interior is differentiated, but with a thick, rigid lithosphere, about ten times the relative size of Earth's, and a small, partially-molten core. The Moon's surface area is larger with respect to its volume than is the case for Earth, so the lithosphere was able to cool to temperatures too low to support tectonic cycling.

H. Origin

- Fission from Earth? No: its mean chemical content differs from Earth's.

- Capture? Unlikely. Captured satellites do exist (e.g. of Mars, Jupiter) but are small, asteroidal bodies.

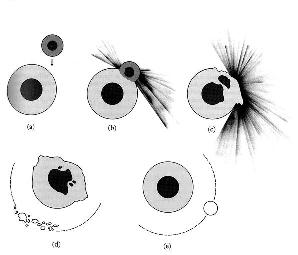

- Collisional ejection favored. A large (perhaps Mars-size)

planetoid hits the young Earth about 4.5 Gyr ago, heating and

expelling material from the outer layers (but not the dense core)

which goes into orbit and accumulates to form the Moon (see drawing).

The hypothetical impactor is often

called Theia.

-

This mechanism is consistent with lunar chemistry: The lunar

surface composition broadly similar to Earth's mantle but with

differences that indicate great heating of the lunar material. During

the impact event, terrestrial rocks are heated to the point that

non-refractory materials evaporate, leaving behind the lighter,

refractory materials, which are then incorporated into the Moon. For

more details,

click here.

Click here for a Quicktime animation of

the birth of the Moon and here for a brief

documentary on recent supercomputer simulations of the Moon's

formation. The painting at the right is a visualization by famous space

artist Chesley Bonestell of the Moon shortly after it had begun to

solidify as seen from the still-molten surface of the Earth.

Click here for a Quicktime animation of

the birth of the Moon and here for a brief

documentary on recent supercomputer simulations of the Moon's

formation. The painting at the right is a visualization by famous space

artist Chesley Bonestell of the Moon shortly after it had begun to

solidify as seen from the still-molten surface of the Earth.

I. History

- The Moon was initally molten after accretion. The highlands were produced from low density magma "foam," which floated to the top of a "magma ocean" and cooled to a solid crust.

- Intense bombardment by fragments/asteroids continued to

about 3 Byr ago, gradually declining with time. See the drawing at

the right. The highlands were subjected to a rain of impacts from

the earliest times.

- At a later time, large impacts penetrated the crust and allowed upwelling of denser interior magma to form the maria. By this time, the general infall of smaller impactors had decreased, so there are fewer craters per unit area than on the highlands.

- Based on Apollo return samples, the large maria formed this way

3.8-4.1 Byr ago. This narrow range in the dates

of big lunar impacts could indicate a special event called the

Late Heavy Bombardment, during which an unusual number of

large impactors reached the inner Solar System. The LHB may have

been caused in turn by

sudden changes in

the orbits of Neptune and Uranus, which induced a large-scale

gravitational instability, scattering planetesimal bodies throughout

the solar system.

- The LHB would have had catastrophic consequences for the surface of Earth as well. Overall, we expect the number of impacts per unit area on Earth to have been somewhat higher than on the Moon (because of "focussing" by the Earth's higher gravity). For more discussion of impacts on the Earth and their consequences for our biosphere, see Study Guide 22.

- Water molecules released from the molten rock or delivered later to the Moon's surface by comets or meteoroids would diffuse off into space because of the Moon's low gravity. Open bodies of liquid water were probably never present on the Moon, whereas they formed relatively early in the history of the Earth.

- The continuing bombardment from smaller objects (down to micro-meteoroids) completely eroded the lunar surface and created the global regolith. Although some astronomers in the 1960's worried that the surface might have been completely reduced to fine dust, in which spacecraft might flounder and submerge, the actual regolith more resembled the cinder-like surface of athletic tracks and provided a firm layer for landers and humans.

J. Tides and Their Orbital Effects

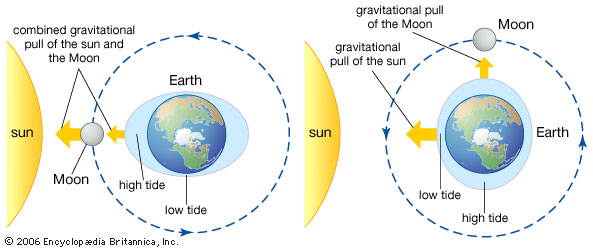

- The gravitational interaction between the Earth and Moon

does more than simply determine their mutual orbits, as described in

Study Guide 8. It has secondary effects

on the shapes of the two bodies.

- The liquid and solid surface of the Earth is distorted by the differential effect of the gravitational forces of the Moon and Sun across the Earth's diameter -- e.g. the fact that the Moon's gravitational force on the side of the Earth facing the Moon is larger than on the opposite side of the Earth. The result is a bulge in the Earth's surface extended both toward and away from the Moon (see the illustration). The situation was first explained by Newton in 1687. The Earth's gravity produces complementary distortions in the solid Moon as well.

- The "tides" are experienced as a rise and fall of the local ocean surface as the Earth's rotation carries a given location under the bulges. They are largest when the Earth, Moon, and Sun are co-aligned, as shown in the figure below:

- Over billions of years, the small changes in the gravitational

field of the Earth caused by the tidal distortions have important

consequences:

- The tidal effect tends to transfer energy from the Earth's spin to the orbital motion of the Moon. This causes the Moon's orbit to increase in size, with the Moon slowly moving farther from Earth. In the Bonestell painting of the young Moon above, the Moon is portrayed as considerably nearer Earth than it is today.

- Tides raised in the body of the Moon by the Earth's gravity act to reduce the Moon's spin. Over time, this has slowed the Moon's rotation to the point that it is now locked in "synchronous" rotation, with a spin period equal to its orbital period, as described above. Synchronous rotation is common among the satellites of the outer planets and also many of the exoplanets we have discovered (Study Guide 11), which always present one face to their host star.

after the first human landing on the Moon (July 1969)

Reading for this lecture:

-

Bennett textbook, Secs. 9.2, 9.3, 10.3

Study Guide 13

-

[Study Guide 14 and Bennett Chapter 6 are optional reading]

Study Guide 15

Bennett textbook: pp. 203-204; Secs. 9.3, 9.5.

Web Links:

-

Slides shown

in lecture (pptx)

Illustrations of Lunar Topography (O'Connell)

Lunar soil samples (O'Connell)

Motions and Phases

of the Moon (O'Connell)

Google Moon (interactive Moon viewing)

Moon

Info at Views of the Solar System

Ex Luna Scientia -- Apollo Program and Lunar Sample Science (textbook for U. Wash. Astro 105, Toby Smith)

Resources on Impact Cratering in the Solar System

Orbital instability and Late Heavy Bombardment (William Bottke) Exploring the Moon (robot and human missions to the Moon; LPI)

The Saturn Moon rockets (the most powerful built before 2022)

The (failed) USSR N1 Moon rocket program

Lunar Exploration (history, photos, other data; NASA, NSSDC)

Project Apollo Photo Archive (Flickr)

Chariots for Apollo (description of Apollo Program spacecraft; NASA)

Apollo Over the Moon (photographs from the Apollo mission orbiters)

The Project Apollo Archive (images, videos, info, links)

Dan Beaumont Space Museum (images and artwork from space program)

Five recommended books on Apollo program Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Mission Apollo Moon Hoax---response from "Bad Astronomy" to the people who have nothing better to do than imagine up improbable government conspiracies about NASA faking the Moon landings. Videos:

-

Apollo 8, the first mission to the

Moon (NASA)

Apollo's Daring Mission (Apollo 8, PBS 'Nova')

Slow-motion Apollo 11 Launch video (NASA)

Apollo 11 - 40th Anniversary Retrospective (USA Today)

Apollo 11: lunar landing and first steps Mitchell & Webb show how NASA must have planned the "fake" Moon landings Simulated flyover of the Moon's Alpine Valley (based on a 3D reconstruction of the surface from space imaging) Animation of post-formation Moon history

Previous Guide

Previous Guide

|

Guide Index

Guide Index

|

Next Guide

Next Guide

|