ASTR 1210 (O'Connell) Study Guide

9. SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, & SOCIETY

| For an essay version of this webpage, click here |

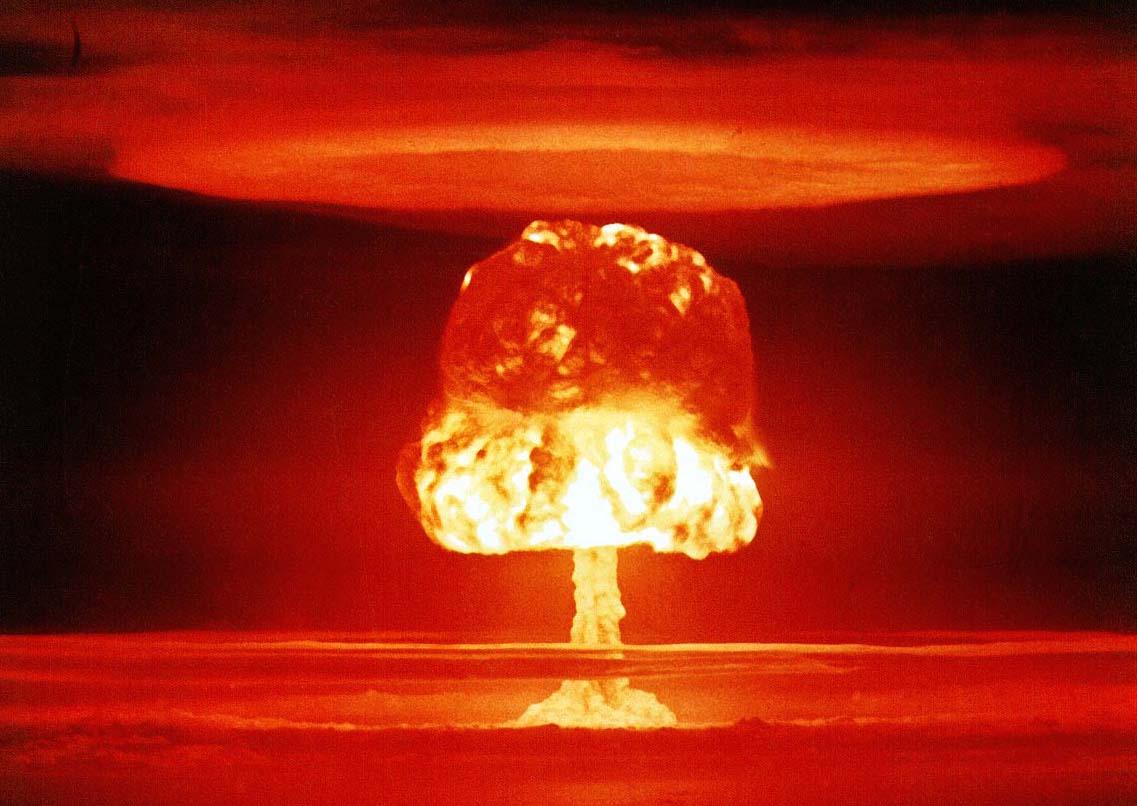

US hydrogen bomb test, 11 megatons, 1954.

The image above is probably what leaps to mind when the subject of "science and society" is raised. This is a famous snapshot of the fireball from theA. Distinctions

It will help to be clear about the terminology:- Science: By my definition, science is the attempt to understand the universe, to build a conceptual framework. This is often called "fundamental," "pure," "unapplied," or "basic" research. Most research in astronomy falls in this category. Important examples of scientific accomplishment are Newton's theory of gravity, Maxwell's discovery of electromagnetic waves, Leeuwenhoek's discovery of microorganisms, and NASA's planetary exploration missions.

- Technology: Technology is the application of

basic concepts to solve practical problems (e.g. shelter, food,

transport, energy, medicine, tools, weapons). Technology may use our

basic scientific understanding but doesn't necessarily in itself

contribute to it. The word "invention" is often applied to

innovations in technology but not normally to scientific

discoveries. Engineering is applied science/technology.

Examples: structural and civil engineering, aeronautics, pharmacology,

and the Internet.

-

Technology always has a societal motivation, whether for

ultimate good or ill, but the main motivation for "basic" science is

simply curiosity and the desire to understand.

- Job descriptions:

-

Scientist: "Be curious"

Technologist: "Be useful"

B. Conversion of Basic Science to Technology

- Science now usually precedes technology

- This was obviously not true for the early technologies (e.g.

fire, stone tools, cloth, ceramics, metalworking, glass), which were

developed through trial and error, building on intuition drawn from

everyday personal and societal experience. Trial and error certainly

still figures in technology development, but the essential

foundations for experimentation since about 1800 have come from

science.

- Critical Conceptual Path: For each

important new technology, we can construct a "critical conceptual

path" of the main steps leading to its realization. Almost all

modern technologies depend on a long list of discoveries in basic

science. Most will go all the way back

to Newton and Kepler.

-

Individuals like Galileo, Einstein or Pasteur have made important breakthroughs,

but progress in science inevitably depends on the contributions of

many people. For instance, a

recent study of the development of a new drug to fight metastatic

melanoma concluded that its critical conceptual path extended back

over 100 years and involved 7000 scientists working at 5700 different

institutions. Most of this path involved basic research disconnected

from immediate commercial or clinical applications.

The recent development of vaccines for the COVID-19 virus is a perfect

example of how basic research underpins essential technology. With

older technology, it normally took years to perfect viral vaccines.

However, the discovery of the structure and function of

the "messenger

RNA" molecule in 1961 began a chain of research that ultimately

led to the very rapid development, in only a few months' time, of

COVID-19 vaccines that use mRNA to induce human immune system

resistance to the virus.

- Key contributions of science to technology:

- Methods: critical thinking, skepticism, rational analysis,

empirical testing, calculus, statistics, double-blind medical trials,

etc.

Knowledge: Newton's Laws of Motion (mechanics), thermodynamics,

electromagnetism, chemistry, biology, hydrodynamics, structure of matter, etc.

- The enabling discoveries in the critical conceptual path are

often motivated by curiosity rather than potential applications.

- This is why politicians and opinion-makers who insist on the

"relevance" of scientific research, especially in terms of near-term

applications, are misguided --- and may even inhibit progress.

"There is no 'useless' research."

---- Nathan Myhrvold, Chief Technology Officer, Microsoft Corporation "There are two possible outcomes [of an experiment]: If the result confirms the hypothesis, then you’ve made a discovery. If the result is contrary to the hypothesis, then you’ve made a discovery."

---- Enrico Fermi, nuclear physicist

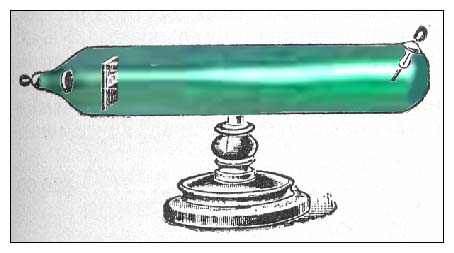

Experimental cathode-ray tube (ca. 1875): forerunner of X-ray and TV tubes.

- The time scale for conversion of basic discoveries to useful

technologies varies enormously

- Examples

- X-Rays (1895): X-Rays

were accidentally discovered by Roentgen in the course of basic

research on the physics of electromagnetic waves using cathode

ray tubes like the one above. Click here for a sample 1896 X-ray. Conversion time to medical

imaging applications: 1 year.

-

This is a good example of a technological problem that couldn't be solved by

trying to solve it. A direct engineering approach to devising a

non-invasive mechanism to examine internal human anatomy would have

failed utterly.

- Human Space Flight (1961): The basic scientific concepts needed to build rockets and navigate them through space had been known since the 19th century, so the investment of large amounts of $$$ (in both the US and USSR) solved the remaining technical problems within 5 years of a political decision to go forward. Conversion time: 280 years (from Newtonian orbit theory, the essential conceptual foundation of space flight).

- CD/DVD Players (1982): Here, the critical conceptual path includes Einstein's work on induced transitions of electrons in atoms (1916), which was the essential idea in creating the lasers that are used to convert digital recordings into electronic signals. (Similar lasers are the basis of data transmission by fiber-optic cables, now the main technology used to drive the Internet.) Conversion time: 66 years.

- X-Rays (1895): X-Rays

were accidentally discovered by Roentgen in the course of basic

research on the physics of electromagnetic waves using cathode

ray tubes like the one above. Click here for a sample 1896 X-ray. Conversion time to medical

imaging applications: 1 year.

- Examples

- Technology is a fundamental test of the validity of scientific ideas

-

Modern technology is applied science. As pointed out

in Study Guide 1, if our science was not

right, then most of our technology would simply not work. Even though

it's not readily visible to us, our everyday experience in modern

societies depends on the quality of our scientific understanding of

nature on scales from the atomic to the cosmic.

-

By the way, this is also the best answer to the notion of "social

constructivism" -- popular with some philosophers and social

scientists -- that prevailing scientific theories are more a product

of social conventions, political currents, or a power hierarchy than

objective data from the real world. Scientists emphatically reject

this argument. They accept that they are subject to all the same

social pressures, foibles, and character flaws as other people. They

make mistakes, exercise bad judgement, and can have strongly

subjective biases (mostly in favor of their own ideas). However, the

difference in terms of the results of science is that the demand for

empirical verification provides an external standard for

determining which ideas have merit, and this ultimately produces

robust interpretations of nature, which can be used to benefit all

mankind. If the lights come on, the airplane flies, the antibiotic

cures, then the "socially constructed" argument goes down the drain.

C. The "Big Four" Benefits of Science/Technology to Society

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

-

None of the refined, modern versions of human technology would exist

without the ability to record vast amounts of information and transmit

it from person to person and generation to generation. Through

medieval times it was possible to convey knowledge on a modest scale

by laborious manual writing and copying and some scattered

experiments with printed material. However, only the advent of

mass-produced printed books based

on Gutenberg's

design of printing presses using metallic movable type (ca. 1440)

opened the doors to the information revolution. Within 150 years, an

amazing 200 million volumes had been printed.

Books ushered in the modern age. Science depended on them.

Universities flourished because the ability to deal with large amounts

of specialized information in books became essential to society.

Beginning in the mid 19th century, information transfer proliferated

thanks to the automated rotary press and inventions like the telephone

and the linotype machine. In the last 30 years, the Internet and

other electronic technologies have accelerated the spread and creation

of information. Their societal impact has not yet matched the

monumental watershed established by the printed book, but the related

looming prospect of

artificial general intelligence would do so.

AGRICULTURAL GENETICS

-

"Genetic engineering," the creation of artificial life forms, is

nothing new. It has been going on for thousands of years (long before

we even recognized the existence of genes). You will be shocked when

you click on this picture of the

most familiar artificial life form. Almost all the food we eat

is derived from deliberate human manipulation of plant and animal gene

pools. (The main exception is wild seafood.) Until the mid 20th

century, the techniques employed were cross-fertilization, selective

breeding, population culling, and other "natural" methods. As our

understanding of genetics matured (ca. 1900-1950), these techniques

became science-based. Eventually, it became possible to directly

manipulate cellular material (ca. 1970+). Molecular biology now

offers an ultimate genetic control technology.

CONTROL OF INFECTIOUS DISEASE

-

The control of the microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi,

parasites) that cause infectious disease is one of the most important

contributions of science & technology. In fact, many of us would not

be alive today without it because a direct ancestor would have died

too early. The COVID-19 pandemic serves as a grim reminder of the

almost-forgotten dire threat of infectious diseases like bubonic

plague, smallpox, tuberculosis, malaria, cholera, polio, and AIDS.

These often swept through human populations, killing huge numbers of

individuals. But as recently as 350 years ago, communicable disease

was thought to be produced by evil spirits, unwholesome vapors,

"miasmas," or other mysterious agents. No one imagined that it was

caused by invisible lifeforms until

Leeuwenhoek

in 1676 used the newly-invented

microscope to discover microscopic organisms. Widespread

production of agents --

"antibiotics"

and

"vaccines" -- that

could attack specific types of harmful bacteria and viruses or prevent

infection in the first place was one of the most important advances in

medical history.

"Public health" consists mainly of systematic methods for

controlling microorganisms.

ELECTRICITY

- Electricity is the primary tool of modern civilization, yet

few people appreciate this or have any idea of how electricity

was discovered or converted to useful technologies. We

explore the development and contributions of electricity in

the next section.

D. Electricity: A Case Study

Electricity is ubiquitous today in all but the most primitive societies. The most obvious manifestation of electricity is in sophisticated electronics: smart phones, DVD players, personal computers, HD TV, video games, and so forth. But these are luxuries, and it should be easy to imagine being able to live comfortably without them---in fact, people did so only 35 years ago. We don't really need fancy consumer electronics, but we do need electricity. Our reliance on electricity is profound, and its use is so deeply embedded in the fabric of civilization that we mostly take it for granted. At least until there's a power failure.-

Electricity supplies almost all of the power we depend on and

is essential for manufacturing, agriculture, communications,

transportation, medicine, household appliances, and almost every other

aspect of modern life. It's easy to overlook the ubiquity of

electricity by thinking only in terms of obviously "electrical"

devices:

-

One crucial example: all the internal combustion

engines used in cars, trucks, locomotives, ships, and planes require

electrical ignition systems.

Two others: refrigeration and water distribution and

purification systems. Imagine the challenges in providing food and

medication to the world's population today in the absence of

electrically powered refrigerators. Anyone who appreciates hot

showers taken indoors is an unknowing admirer of electric pumps.

-

The most powerful control systems in use today are, of

course, computers and microprocessors. These outperform human

brains in raw processing speed by factors of many millions and have

advanced to the point of duplicating or superseding human performance

in games like chess or in operating an automobile. They are used on a

scale that would have been inconceivable to people only 75 years ago.

Nonetheless, that generation also depended on electricity for control

systems: think of the

telephone

operator plug-boards of the "one ringy-dingy" era.

-

More seriously, if we somehow became unable to use electricity, our

economy would collapse overnight, taking our Gross Domestic Product

back to the level of about 1900. More than half of the population

would probably die off within 12 months, mostly from starvation and

disease.

The 2012-14 NBC-TV

series "Revolution"

showed an action-oriented version of what a fictional post-electricity

world might be like (though one where everybody still manages to have

good hair).

An all-too-real threat to our electrical infrastructure

is posed by magnetic activity on the Sun, particularly "coronal

mass ejections." In July 2012

the Earth

only narrowly missed a CME from a solar superstorm that could have

devastated our electrical grid.

Development of Electric Technology

Electricity is the everyday manifestation of electromagnetic force, the second kind of inter-particle force (after gravity) that scientists were able to quantify. Here is a very brief history of our understanding of EM force, divided between "basic" and "applied" developments:- ca. 1750-1830: Coulomb, Orsted, Ampere, Volta, (Benjamin) Franklin, and other physicists explore the basic properties of electric and magnetic phenomena. Orsted and Ampere show that an electric current moving in a wire could produce a magnetic field surrounding it. Basic.

- Faraday (1831)

(experimental physicist): discovers electromagnetic induction.

Basic.

- Faraday discovers that a changing magnetic field could

induce an electric current. Together with the fact that an

electric current could induce a magnetic field, this demonstrates the

symmetry of electromagnetic phenomena.

This is also the key to the development

of electric generators

and motors, which convert

mechanical force to electrical force, and vice-versa, using magnetic

fields. These are two of the essential technologies of the electric

age.

Since 1850 most large-scale electrical generators rely on

steam

engines to help convert mechanical energy into electrical

energy. (Various types of wood- or coal-burning steam engines had

been developed in Great Britain in the period 1760-1800 and were

so effective at increasing economic productivity in commercial

mining and textile manufacturing that they became the basis of the

Industrial Revolution.) Today,

steam turbine engines are most commonly used in large

electric generators.

Applied.

- Edison (technologist) and others (1830--1900) develop practical

electrical generators, motors, distribution grids, and appliances.

Applied.

-

Many people think Edison "invented" electricity. He didn't.

He invented a large number of electrical appliances---including

the electric light, tickertape machines, the motion picture camera &

projector, etc. But these all depended on a pre-existing supply of

electricity and the knowledge of how to use it---all

contributed by basic research in physics.

- Readily available electricity stimulates the invention of the telegraph (1830's) and telephone (1870's), fundamentally changing human communications (and, needless to say, behavior). Applied.

- Maxwell (physicist): in 1865, Maxwell deduces equations giving a

complete description of the observed electrical and magnetic (EM)

phenomena. From these, he predicts the existence

of electromagnetic

waves traveling at the speed of light and thereby

demonstrates that light is an electromagnetic phenomenon, one

of the most important discoveries in the history of science.

Basic.

- The fact that these EM waves can have arbitrary wavelengths

implies the existence of a broad

electromagnetic spectrum, which includes the

regions we now use for radio and television. No one had

even suspected the existence of this vast spectrum, which is

mostly invisible to our eyes.

- Hertz (physicist, technologist): accomplishes the first generation & detection of artificial radio waves (1887). After he demonstrated the existence of radio waves, Hertz admitted that he could not see any practical applications for them. Eight years later, as described above, Roentgen discovers the X-ray region of the EM spectrum, the practical applications of which, by contrast, were immediately apparent. Both Basic and Applied.

- Tesla, Marconi and many others develop methods for routine transmission and reception of EM radio waves. Just as important are new inventions -- such as vacuum tubes (1907) -- for modulation of EM waves so that an intelligible signal could be impressed on them. This leads to commercial radio (1920) and television (1936). All of our "wireless" technology today is similarly based on radio waves. Applied.

- The development of quantum mechanics

(Basic) after 1925 leads to the

miniaturization of electrical circuits using solid-state materials

like silicon and the invention (Applied) of the

transistor

(1947) and

integrated

circuit (1959), which are the central components of all the

electronics in use today.

- The quantum-based technologies are probably responsible for at

least 50% of our Gross Domestic Product today -- so one of the

largest contributors to our economic well being was developing an

understanding of how electrons move in chunks of silicon. Who

could have predicted that?

E. A Brave New World

The cumulative effect of science-based technologies, including the myriad applications of electricity and electromagnetic waves, has been profound. Living conditions for most human beings have been radically transformed for the better since 1500 AD. By every measure -- freedom, equality, wealth, health, safety, comfort, opportunity, meaningful work, and so on -- the present circumstances for the great majority of all people are an unprecedented improvement over the past. They are an improvement even over the lifestyles of the most privileged individuals in earlier history --- there aren't many sensible people today who would trade indoor plumbing for rubies and emeralds.-

These six

charts show the dramatic improvement over the last 200 years

in important indicators like poverty, child mortality, and literacy.

The long-term historical decline in violence among human

societies is illustrated in this slide presentation.

-

In this vein, also think about this: When you get some kind of injury

or malady and you go to a doctor, you automatically assume you will be

effectively treated and usually cured. That's a new assumption. It

wasn't true throughout all of human history until about 100 years ago.

In fact, one historian of medicine noted that before about 1850, "most

people were fortunate in being unable to afford treatment" ---

because medical care then was often

counterproductive, brutal, and dangerous.

- Up to the late 18th century, implementation of new technologies rarely occurred in a period shorter than a human life.

- Today, technological change is much faster and therefore more obvious. The best recent example: smartphones, introduced less than 20 years ago, have already dramatically changed the daily behaviour of billions of people.

- It is hard to visualize how rapidly modern technology has

emerged --- in only about 200 years out of the 200,000 year

history of our species.

-

Picture even the most far-sighted thinkers of the 18th century --

Thomas Jefferson or Voltaire, say -- trying to figure out how a

television set works. It is utterly foreign to the

familiar technologies of their era. Its operation would appear

to be "magic."

F. Technological Excesses

The Dilemma

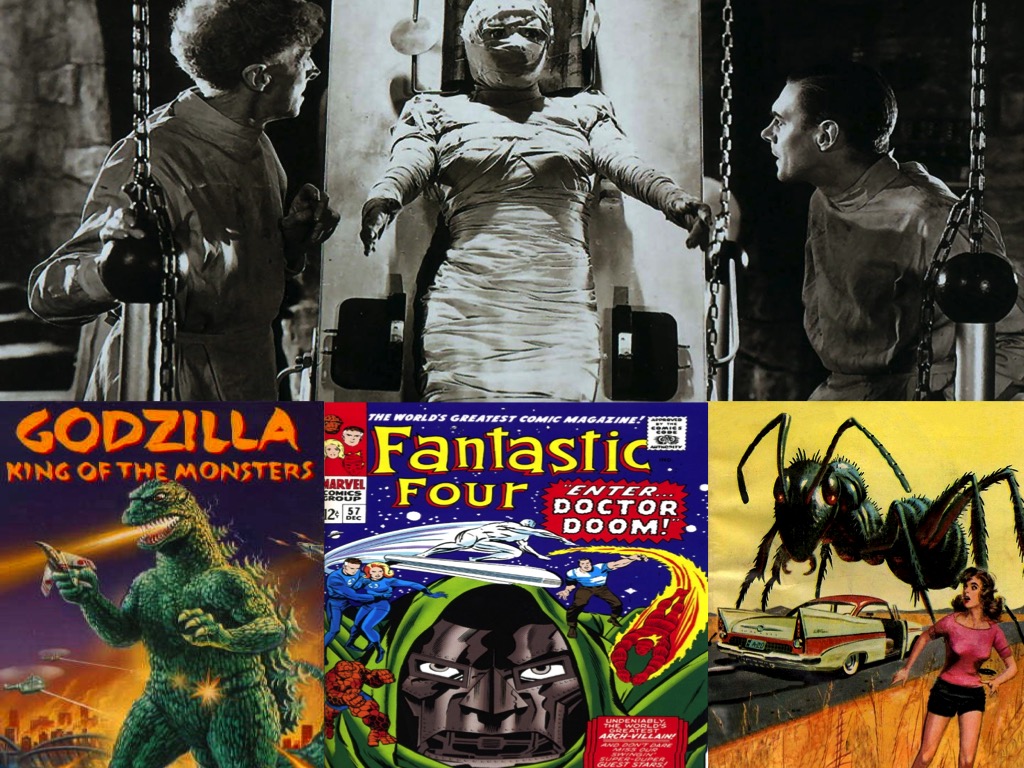

Technology is never an unalloyed good. Given its rapid emergence, it is not surprising that modern technology has produced numerous unforeseen side effects and difficulties. All technology carries risk. Powerful technologies are obviously capable of both great benefits and great harm -- the example of fire being the historical standard. They will frequently rechannel human behavior, with consequences that are hard to predict and can be deleterious. Technologies convey important advantages to groups or societies that possess them, and they can be used to oppress or exploit other groups -- as in the case of the Aztecs (see Study Guide 5). As appreciative as we ought to be of the technologies that are the foundation of our material lives today, and as impressive as are new medical therapies or innovations in entertainment, there is a strong thread of discontent with technology that runs through our society. Some of this stems simply from frustration when technologies -- usually complex ones -- fail to work well or don't live up to inflated expectations. But in the last 50 years, dangers attributed to science and technology have often been given more prominence than their benefits. People these days are often more suspicious than appreciative of science and technology.-

The perceived threats include environmental pollution, habitat

destruction, environmental disease, global warming, nuclear weapons,

nuclear poisoning, artificial intelligence, human cloning, and genetic

engineering, among others. Such problems have often been vividly

portrayed in literature and other media going back to

"Frankenstein,"

written by Mary Shelley in 1816,

such that the notion of

unthinking scientists unleashing disasters on the world has

become a staple of popular culture in the burgeoning genre of

dystopian fiction. Some examples:

- A classic case of "irrational exuberance" over a new and initially highly beneficial technology was the unthinking widespread application of the insecticide DDT. Early use of DDT during World War II accomplished a miraculous suppression of the mosquitos that transmit malaria, one of the greatest historical killers of human beings. But by the 1950's its use had been taken to truly absurd levels and led to serious unanticipated environmental damage. That, in turn, was the genesis of the book that founded the environmental protection movement, Silent Spring (1962), by Rachel Carson.

- A related rapidly emerging threat: the flourishing of organisms (bacteria, viruses, agricultural pests) that are resistant to the chemicals normally used to control them because of overuse of the control agent. By eliminating their natural enemies, overapplied agents allow resistant strains to proliferate. An all-too-common example: people demand antibiotics to try to control a viral infection -- but antibiotics work only against bacteria, not viruses. Hospitals are more dangerous places today than they were 30 years ago because of the overuse of antibiotics. Industrial agriculture contributes to the problem by the unnecessary introduction of antibiotics to animal feed and by massive applications of pesticides and herbicides.

- An important unintended technological threat, one which played a central role in recent presidential elections but which was unrecognized by most voters, is the widening displacement of human labor by machines and computers. Although these reduce drudgery and improve efficiency, they have also produced major changes in employment demographics, suppressed wages, and increased social stress. More generally, the workforce in advanced societies is bifurcating between people who are able to deal with complex information and others. Most of the good lifetime careers are in the former group. People without above average intelligence and analytical skills will find themselves further marginalized with every passing decade. Recent advances in the capabilities of artificial intelligence (AI) software are raising growing concerns over displacement.

- Nuclear

weapons were, of course, always intended to be destructive,

and they were used as intended by the US to attack Japan in 1945 and

bring World War II to an end. But the long-term dangers of

radioactive

fallout -- downwind deposition of radioactive particles and

the most serious large-area consequence of using nuclear weapons --

were not fully understood until well after their first use.

Uncontrolled fallout effects greatly increase the destructiveness of

these weapons. In the wake of the US attacks and subsequent

controversies over weapons, fallout, and nuclear power plants, many

people came to wish that these technologies had never been invented.

Some argued that our knowledge of nuclear physics is a bad thing.

- But nuclear physics also created nuclear medicine -- for

example, using radioisotopes as biochemical tracers -- without

which modern pharmacology, radiation therapy,

and magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI)

wouldn't exist. Biomedical applications of nuclear physics save

millions of lives each year. Vastly more people have benefitted from

nuclear technology than have been harmed by it (so far).

- A major but rarely discussed danger to a highly technological society like ours is its vulnerability to potential disruptions. A pivotal feature of modern society is how complex, interdependent, and highly specialized it is. It takes tens of thousands of people working in coordination to produce and deliver even a single item. No one person could build a radio, or a lawn mower, or even a box of Cheerios from scratch. There is a highly integrated system involving scores of specialities across a dozen different industries behind the production and distribution of any of those things. Without being conscious of it, we live in a huge web of specialization and expertise. Such a system is inevitably fragile and can be easily disrupted by incompetence or by natural, political, malevolent, or cultural interference. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed some of the fragilities of modern societies.

- There may be no more timely example of a technological boomerang than the clearly emerging negative social and political consequences of wildly popular social media Internet sites, which provide huge audiences for unfiltered human expression. The vast anonymous user base on social media is a font of the most irresponsible behavior imaginable. On the other hand, it's a terrific psychological experiment in cataloging the depths of human stupidity and depravity. The digital environment today, especially in conjunction with artificial intelligence, bears some unpleasant similarities to the fictional Krell Machine, which wiped out its creators overnight in the 1956 movie "Forbidden Planet."

Mitigation

How should we respond to adverse technological "feedback"? A first impulse might be to argue that the associated technologies are so threatening that we ought to suppress them --- but this ignores the abundance of benefits they bestowed in the first place. The problem, a difficult one, is to achieve a healthy balance that preserves most of the advantages while mitigating the serious disadvantages of important technologies.-

Societies have been wrestling with this for the last 200 years. A

fundamental obstacle to intelligent planning is the inevitable time lag

between introduction of the new technology and the appearance of its

major drawbacks --- especially if it has been widely adopted in the

meantime. Another is that amelioration often demands a change in human

behavior, not just the technology. The need to reduce our "carbon

footprint" to mitigate global warming is a contemporary example.

It's important to appreciate that many of the negative effects of

technology are only identifiable because of modern technology

itself. Without our sensitive instruments and diagnostic tools,

we would be poorly informed about the impact of environmental

pollution on water or air quality, the ozone layer, global warming,

induced diseases, and so forth. And achieving amelioration of the

negative effects will also depend on science and technology

themselves. A retreat from modern science or technology would produce

vast suffering.

Technology could, in fact, solve many of the environmental problems we

face --- assuming it is carefully designed and properly applied.

Failures to adequately address such problems are rarely caused by

serious technological barriers.

Technology could, in fact, solve many of the environmental problems we

face --- assuming it is carefully designed and properly applied.

Failures to adequately address such problems are rarely caused by

serious technological barriers.

-

As an example, consider the fact that modern technology has made it

possible to take one of the most toxic materials known

(botulinum toxin, 1000 times more deadly gram-for-gram than

plutonium) and turn it into the cosmetic

Botox that thousands of

people happily have pumped into their faces every day.

G. Technology's Ultimate Threat: Population Growth

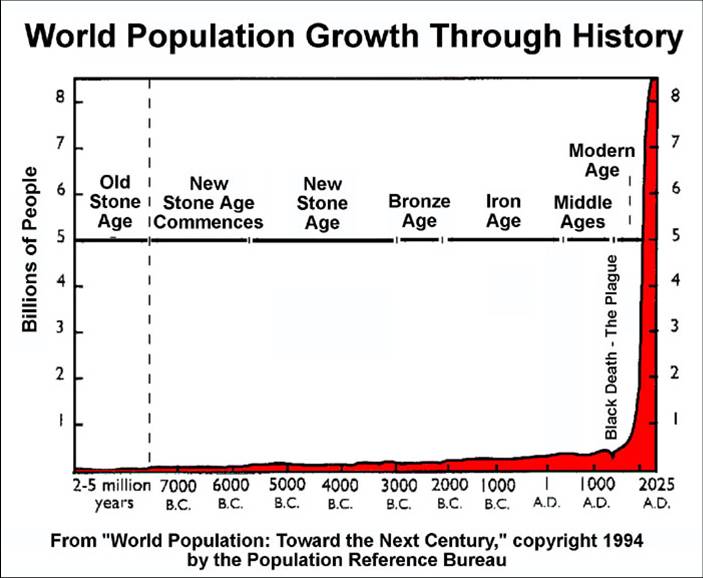

The root of almost all of our environmental problems is not any one technology. Instead it is the inevitable product of all of them, and it is something that almost everyone agrees is a good thing: modern technology keeps people alive. Life expectancy at birth has roughly doubled since 1850. Without a corresponding downward adjustment in birth rates, the increase in the human life span creates an imbalance between birth and death rates.-

Obviously, the increase in the population in any year will

be proportional to the population itself.

In any situation like this where the rate of change of a quantity is

proportional to the quantity itself, the solution of a

simple differential equation shows that the value of the quantity

will "exponentiate", as follows:

-

q = qoegt, where e = 2.72, t is time,

qo is the quantity at the start, and g is the constant of

proportionality.

In the case of population, g is the net birth

rate, i.e. the fractional excess of births over deaths in a

year.

As long as g is positive, the result is that q grows

continuously and at an ever increasing rate.

The figure to the right shows the simplest exponential function,

the case where g=1.0 and qo=1.0.

See this article for more information.

A similar formulation applies to a number of other real-world

situations: for example, to a savings account subject to

compound interest and to the interest owed on student loans.

All college students would be smart to take the time to understand

exponential growth.

-

A doubling time of 35 years implies that the population after

three doubling times (105 years) would be 2x2x2 = 8 times as

large as the starting population.

The doubling time is inversely proportional to

the growth rate g.

2% is close to the actual growth rate for the human population between 1960

and 1999. At that growth rate, starting from 6 billion people in the

year 2000, the total population would be 44 billion -- 7.4

times larger -- by the year 2100. It would be 330 billion

by 2200. If ASTR 1210 scaled in proportion, there would be 8000

people in this class!

For an instantaneous estimate of the US and world populations, click

on the:

US Census

Bureau POPClock.

-

This graph should scare you. For a little more context, consider

that the spike shown there constitutes only 0.00001% of the

history of planet Earth. And yet the humans born in that spike

have already begun to transform the Earth's physical character.

-

Any fixed resource (water, land, fuel, air), no matter how

abundant, is ultimately overwhelmed by continuous growth of

population.

Of course, as we approach exhaustion of any such resource, there will

be a negative feedback effect which will drastically

increase the death rate until the population stabilizes or decreases.

That will stop the exponentiation, but we obviously would prefer

not to rely on that solution.

We may not yet have reached the "carrying capacity" of the Earth, but we

are getting closer. We are probably already well in excess of the

population that is compatible with easy resource sustainability.

-

The "Green

Agricultural Revolution" has allowed us to stave off the

widespread famines that would have been inevitable if we had been

limited to 1950's technology over the past six decades. Nonetheless,

demand from the growing human population has already crossed

critical local resource thresholds in many areas, as attested by

famines and other privations scattered around the world.

One of the most dramatic of these is the catastrophic collapse of

some world-class fisheries

(e.g. Atlantic

cod), previously thought to be inexhaustible. Another is the

surge of African refugees into southern Europe, precipitated by a

decrease in arable land and mean birth rates that are as high as 7

children per woman. And human contamination of the Earth's

atmosphere is already affecting the

climate in the form of global warming.

Detailed mathematical models of the confrontation between finite

resources, population growth, and the possible mediating effects of

technology have been made over the last 60 years. The most famous of these

was The

Limits to Growth, published in 1972. It was widely criticized

because it predicted that a global economic collapse would occur

sometime in the 21st century. However, some

more

recent assessments have shown that the trends it predicted were

reasonably accurately forecast. For an overview of the possible

consequences,

see The Great Disruption by Paul Gilding. Governments should be

taking such forecasts much more seriously than they do.

- For instance, at this rate, we must find the wherewithal to

feed a minimum of an additional 80 million people (one quarter of the

population of the USA) each year, every year.

- At first, this sounds like a fine way out, assuming the technical

problems of travel to Mars and sustenance once we are there can be

solved. But simple migration to other planets cannot cure the

exponential population growth problem.

At a 1% growth rate, the doubling time for the human population is

only 70 years, less than a typical human lifetime. Suppose we reach

the limits of Earth's resources in the year 2100 and immediately start

sending the excess population to Mars. In only 70 years (i.e. in

2170) we will have reached the limit of Mars as well, despite the

tremendous financial investment made to move people there. Migration

doesn't offer much respite in the face of exponential population

growth!

-

Population control is not a technologically difficult problem;

effective innovations like the birth control pill are readily

available. There are, of course, serious ethical, not to mention

political, quandaries in attempting to control or reduce the human

population, but it is becoming obvious that these must be

intelligently confronted soon.

Needless to say, prospects here are not good. The "zero population

growth" movement that flourished in the late 1960's has faded in the

face of misguided optimism and political resistance. You would be

hard pressed to find American politicians for whom population control

is a serious issue, let alone a high priority. In fact, policies on

all sides of the political spectrum, including those embedded in the

current federal tax code, are to encourage population growth.

H. Science and Technology Policy

| "Technology moves faster than politics" --- Yuval Harari |

- Obviously, it must first be able to recognize important needs and to predict useful sci/tech initiatives

- Unfortunately, the track record of technological prediction is

dismal. For example, consider a 1937 US National

Resources Council prediction

of important inventions for the following 25 years (1937--62):

- A few hits---e.g. TV, plastics---but many more misses.

- The leading predicted technology was the "mechanical cotton picker." Hmmm...

- Among the technologies not predicted but actually developed during just the following ten years were: antibiotics, nuclear weapons, nuclear medicine, jet aircraft, nylon, radar, and digital computers. Oops.

- Perhaps the key technology missed in the NRC study was the transistor, invented in 1947 based on developments in the quantum mechanics of solid state materials. This was later transformed into integrated circuits, microprocessors, and the myriad of other electronic components that drive our high-tech world today..

- But the private sector can be just as nearsighted as any lumbering

government bureaucracy.

- In 1994 Microsoft, the Godzilla of software

corporations, decided the Internet was a passing fad and planned to

ignore it in product development. QED.

- In the early 21st century we are entering an era of technological transformation, similar to that produced by physics and chemistry in the 20th century, based on molecular biology, hyper-scale information processing, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, and bio-electronics. Few, if any, scientists, government officials, or corporate leaders are perceptive enough to accurately forecast what this will bring only 25 years from now. As always, both benefits and risks have the potential to be enormous.

|

"We've arranged a global

civilization in which most crucial elements profoundly depend on

science and technology. We have also arranged things so that

almost no one understands science and technology. This is a

prescription for disaster. We might get away with it for a while,

but sooner or later this combustible mixture of ignorance and

power is going to blow up in our faces." |

Reading for this lecture:

-

Study Guide 9

1937 NRC Study: Technological

Predictions vs. Reality

Optional exercise: Try to identify something in your home that was

produced and delivered to you without the use of electricity.

Web Links:

-

An essay version of

this webpage

Brandt's timelines of key

developments in science and technology to 1993

Wikipedia Online Encyclopedia entries:

A

biography of Faraday (Royal Institution)

The Edison Papers

Exhibit on cathode ray tubes and discovery of the electron

Information on electric power generation (from How Things Work by Louis Bloomfield)

Information on electric motors (from How Things Work by Louis Bloomfield)

Invention of the transistor

UVa Virtual Lab (guide to transistors, integrated circuits and other modern electronics)

Britney's Guide to Semiconductor Physics Smarter than you thought? History of computer hardware and software (R. E. Wyllys) Here's a bizarro monument proposed by a leading 1920's enthusiast for the wonders wrought by electricity Invention of nuclear weapons

The Nuclear Weapons Archive

The threat of "nuclear winter"

The Making of the Atomic Bomb by Richard Rhodes (QC773 .R46 1986 in UVa Library) A sampling of dumb quotes about technology (P. Ekstrom)

Top-30 Failed Technology Predictions (Listverse) "What's the Use of Basic Science?" (article by C. H. Llewellyn Smith, former director of CERN) 1937 NRC Study Technological Predictions vs. Reality World Population Clock (worldometer)

Fundamentals of Population Growth and Resource Exhaustion (A. Bartlett)

The Wizard and the Prophet, by Charles Mann, describes the two divergent paths toward confronting human population growth

Bill Maher on population growth and Malthusian limits (video)

Update of the "Limits to Growth" study predicting societal collapse this century

Guns, Germs, and Steel by Jared Diamond: review by J. Bradford DeLong of this important book about the influence of environment and technology on societies The Visual History of Decreasing War and Violence (from OurWorldinData.org) The Return of the Krell Machine (by Steven Harris) -- an ultimate instrumentality from science fiction. A portent of a modern social media meltdown?

-

"Colossus

- The Forbin Project" -- a classic 1970 science-fiction film warning

about the dangers of artificial intelligence.

Previous Guide

Previous Guide

|

Guide Index

Guide Index

|

Next Guide

Next Guide

|